As I pursue the Pre-Raphaelites, I find it is the small details that captivate me, pulling me further and further down the rabbit hole. One tiny detail that delighted me recently is this glimpse of what’s on the mantle in Burne-Jones’ sitting room.

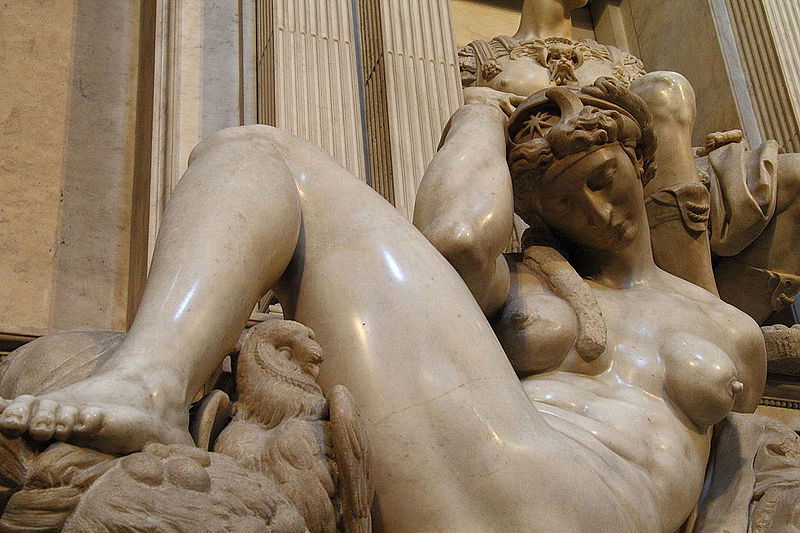

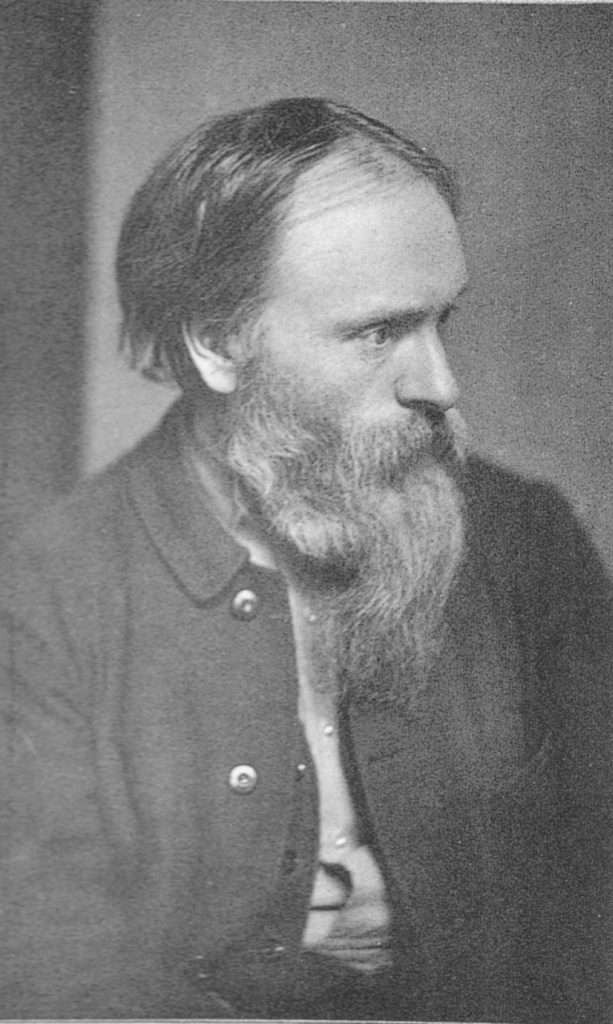

The photo above was taken by photographer Frederick Hollyer, who recorded several Pre-Raphaelite artists and a wide assortment of notable Victorian figures. In The Last Pre-Raphaelite, biographer Fiona MacCarthy identifies the painting seen above the fireplace as W.B. Richmond’s portrait of Burne-Jones’ daughter Margaret, and she also notes casts of Michelangelo’s Night and Dawn sitting on the mantelpiece.

It was Michelangelo that caught my attention. The mention of the name stirred up vague memories of reading Burne-Jones’ comments about the Old Master during his youthful visits to Italy, crucial visits that had an impact on his development as an artist. I began to search for images of Michelangelo’s original Night and Dawn. I needed a closer look.

Thus, my descent into the rabbit hole began.

Searching for Night and Dawn was itself a compelling journey, and to chronicle that would take up too much space here. I will say that their home, the Medici Chapel, is a fascinating place to read about, and I could look at pictures of its interior for hours. This unlikely article in the New England Journal of Medicine raises the possibility that the woman depicted in Michelangelo’s sculpture of Night exhibited symptoms of breast cancer.

SmartHistory has an interesting video introduction discussing the Medici Chapel.

Burne-Jones evidently felt strongly about Michelangelo. His wife Georgiana records in Memorials of Burne-Jones that a disagreement about the artist created a serious division between Burne-Jones and art critic John Ruskin, a close friend. “Ten years after the evening at Denmark Hill when the thing happened, Edward said of Ruskin’s lecture on Michelangelo: ‘He read it to me just after he had written it and, as I went home I wanted to drown myself in the Surrey Canal or get drunk in a tavern — it didn’t seem worth while to strive any more if he could think it and write it.'”

(I’m purposely not going to share what Ruskin wrote that so irritated Burne-Jones, because I want to give you the chance to go down your own rabbit hole.)

Georgiana also wrote that on his visit to the Sistine Chapel, her husband had a unique way of appreciating Michelangelo’s work on the magnificent ceiling:

“In the Sistine Chapel he was made happy by finding the ruin of the frescoes, as well as well as their obscurity, much exaggerated by report. So he bought the best opera-glass he could find, folded his railway rug thickly, and, lying down on his back, read the ceiling from beginning to end, peering into every corner and revelling in its execution.” (Memorials of Burne-Jones, vol. II)

Fiona MacCarthy writes about his visit to Michelangelo’s Casa Buonarroti in her excellent biography, The Last Pre-Raphaelite:

“Back in Florence Burne-Jones fitted in an aficionado’s visit to the house of Michelangelo, which had only opened since 1858. Here, in a small room, he saw the artist’s walking sticks, his slippers and his writing table, in another room his papers, poems and letters. Burne-Jones carefully examined the wax and clay models, a relief in marble, wonderful drawings and studies, frustrated that nothing had been photographed. If only he could have kept some visual records. ‘It is’, he notes, ‘a quiet beautiful house and one can realize the life in it.’ Before he left Florence he returned to Santa Maria Novella, to his favorite ‘green cloister’. In Genoa he drew the orange trees, the olive trees, the nearby hill towns, making studies of the local architecture in a frenzy of departure from beloved Italy.” (MacCarthy, Fiona. The Last Pre-Raphaelite: Edward Burne-Jones and the Victorian Imagination. Faber and Faber 2011)

In a letter Burne-Jones wrote to the daughter of a friend, he listed sights she should see on her own Italian journey. He urged her to “go to the house of Michelangelo and kiss his slippers, as I did.”

When Burne-Jones traveled, he kept notebooks where he sketched and chronicled his impressions. It occurs to me that jotting in the notebook, gazing at Michelangelo’s work through opera glasses, and his visit to the artist’s home are all evidence of Burne-Jones’ own rabbit hole.

I was interested in finding anything Burne-Jones had to say about Michelangelo and was especially hoping to perhaps find a mention of the copies of Night and Dawn. I read all the instances of Michelangelo’s name appearing in Memorials of Burne-Jones and when I came to the bit on page 257, something felt palpably different. I needed to go back a few pages to experience the full context. The chapter is filled with his friendship and conversation with Dr. Sebastian Evans, a journalist and political activist. Part of their conversation grabbed me instantly:

“There are lots of people who have no ‘call’ at all. They don’t count –they are no more fools than they are wise for not having it. The real fool is the man who hears the call and doesn’t obey it. To do any real good, you must work to the best advantage. What you have to do is express yourself — utter yourself, turn out what is in you — on the side of beauty and right and truth, and of course you can’t turn out your best unless you know what your best is. You, for instance, start a rag of a newspaper — I cover an acre of canvas with the dream of the deathbed of a king who you tell me was never alive — why? Simply because for the life of us we can’t hit on any more healing ointment for the maladies of this poor old woman, the world at large. Our religion is the same. There is only one religion. ‘Make the most of your best’ is common sense and morals.” (Memorials of Burne-Jones, vol. II)

I was moved by the depth and simplicity of Burne-Jones’ thought. Heed your call in life, whatever it may be, and do your very best. Do your best to give to the world what you feel called to do. And why should we do that? Because this is how we heal those around us and, if our work lasts like Michelangelo’s and Burne-Jones’, those who come after us.

One person cannot heal the world, but collectively we make the world a better place if we view our skills and talents not only as gifts we’ve been given, but also gifts we generously present to the world.

In the same passage, he goes on the share his feelings on the Biblical concept of the Day of Judgment:

“Day of Judgment? It is a synonym for the present moment — it is eternally going on. It is not so much as a moment — it is just the line that has no breadth between past and future. There is not, cannot be, if you think it out — any other Day of Judgment. It is not in the ‘nature of things’. The Dies irae dies illa is everlastingly dissolving the ages into ashes everywhere. It is nature herself, natura, not past or future, but the eternal being born, the sum of things as they are, not as they have been or will be. What I am driving at is this: We are a living part, however small, of things as they are. If we believe that things as they are can be made better than they are, and in that faith set to work to help the betterment to the best of our ability however limited, we are, and cannot help being, children of the Kingdom. If we disbelieve in the possibility of betterment, or don’t try to help it forward, we are and cannot help being damned. It is the ‘things as they are’ that is the touchstone — the trial — the Day of Judgment. ‘How do things as they are strike you?’ The question is as bald as an egg, but it is the egg out of which blessedness or unblessedness is everlastingly being hatched for every living soul. “

Burne-Jones’ idea moved me. I don’t want to get into theology, because for me this goes beyond that. What his passage makes me think is that we often go through our lives as if our daily actions culminate in something big that will happen in the far away and shadowy future or, like the Day of Judgment, at the very end of our days.

But what if we viewed this Day of Judgment as Burne-Jones did? For him it was not a dramatic ending where it was decided if we should be heaven-bound or damned, but every moment of our lives. Every single moment. And the outcome of the moment can be summed up by asking the simple question, “Did I make things better or worse?” Perhaps a follow up question could be added, based on his earlier statement: “Did I do my best?”

I read the passage again that brought me to Burne-Jones’ exchange in the first place: Michelangelo.

“‘Have you faith, my dear? Do you ever think of this poor old woman, our Mother, trudging on and on towards nothing and nowhere, and swear by all your gods that she shall yet go gloriously some day, with sunshine and flowers and chanting of her children that love has and she loves? I can never think of collective humanity as brethren and sisters; they seem to me ‘Mother’ — more nearly Mother than Mother Nature herself. To me, this weary, toiling, groaning world of men and women is none other than Our Lady of Sorrows. It lies on you and me and all the faithful to make her Our Lady of the Glories. Will she ever be so? Will she? Will she? She shall be, if your toil and mine, and the toil of a thousand ages of them that come after us can make her so!'”

“Afterwards he said: ‘That was an awful thought of Ruskin’s, that artists paint God for the world. There’s a lump of greasy pigment at the end of Michael Angelo’s hog-bristle brush, and by the time it has been laid on stucco, there is something there that all men with eyes recognize as divine. Think of what it means. It is the power of bringing God into the world — making God manifest. It is giving back her Child that was crucified to Our Lady of the Sorrows.'”

Burne-Jones speaks of the world collectively as “Mother” and “Our Lady of the Sorrows” and the thought of that brings to my mind the idea of a constant and everlasting exchange. Mother nurtures, we should nurture her in return. I believe he is suggesting we do this by following our calling, doing our best, and actively contributing to making things better.

I read these passages more than once. I pondered them. I transcribed them. I felt energized and grateful for them.

A realization dawned on me: I was just looking for two statues. Two beautiful inanimate objects on a mantle. That’s all I was looking for, and it led me to glorious ideas about the world and our place in it.

What a gift.

A rabbit hole isn’t the bottomless pit of interest I always assumed it to be. I love using the phrase “rabbit hole,” because for me it conjures up both Alice in Wonderland imagery and falling into a consuming passion that feeds my brain and my soul. Yet it is not just falling blindly into a hole, it is diving wholeheartedly into a journey. Do we know where that initial dive will lead or how the journey will end? That mystery contributes to the delight of the rabbit hole itself.

I have spent a lifetime burrowing down an assortment of rabbit holes, but I only just realized that the seemingly insignificant details that start a journey are never small in the end. They’re the dots that make up a dot-to-dot drawing.

I saw a photograph of Burne-Jones’ sitting room and I spied with my little eye two Michelangelo creations. That dot led to Burne-Jones’ journeys through Italy, the home and work of Michelangelo, and a conversation that spoke to me in a way that I have not clearly defined, if I ever choose to define it at all.

In writing that last sentence, I just realized the true beauty and purpose of a rabbit hole. You think it leads away from you; you are pursuing something interesting that exists outside of yourself. Then it leads right back to you and pierces your heart and there you are, no longer a happy prisoner of just any old rabbit hole, but the keeper of the keys, the carrier of the rabbit hole and the caretaker of the lessons you have learned there.

Thank you for this! I have read Georgiana’s Memorials of her husband without picking out the parts about Michelangelo particularly, and they are really fascinating. I like his philosophy too. It is quite simple (do what you love, do it to the best of your ability, and try to leave things better than you found them), but far from easy to practice! I have a problem with the rabbit holes though. One can be forever going down them (e.g. via Twitter) and then perhaps there is less time for those nobler efforts!

This is utterly beautiful. Thank you for falling down that rabbit hole, Stephanie — and then coming back with wisdom to share, and a tale to tell.

Thank you so much, Terri.

Some very interesting thoughts there. I think Burne Jones was a man of great depth – in photographs he always has a haunted look. Recently I have been reading Josceline Dimbleby’s account of her own journey down a rabbit hole starting with one of BJ’s paintings and leading to her discovery of a secret love affair. She quotes some of BJ’s love letters and they are truly amazing. What Burne Jones says about the day of judgement being always in the present is an interesting idea – reminds me of the present day fascination that people have with the idea of ‘mindfulness’. The Virgin Mary representing the whole of suffering humanity is also an interesting thought. Usually in Christian imagery, humanity is portrayed as a bride, with the wedding feast of the lamb (Christ) as the culmination of history. But thinking of it as the restoration of Christ to the suffering mother (through doing one’s best in the present moment) could be a different way of looking at it.