Elizabeth Siddal made great contributions to the Pre-Raphaelite movement; she appears in a number of important works. After posing for Deverell, Holman Hunt, Millais, and Rossetti she bravely moved to the other side of the easel and became a Pre-Raphaelite artist in her own right. She has fascinated me throughout my adulthood and today I’d like to explore the many faces of Elizabeth Siddal as seen through the Pre-Raphaelites.

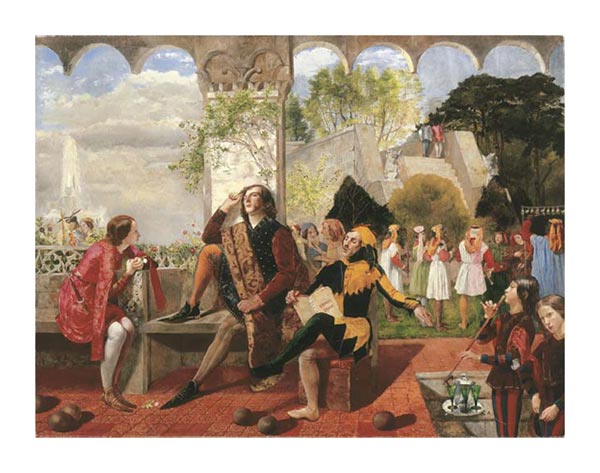

Elizabeth Siddal was discovered by artist Walter Deverell, who needed a model to pose as Viola from Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night. Viola is in disguise, so for her first foray into the art world Siddal donned the medieval costume of a male. To wear such a costume with so much leg showing wasn’t proper behavior for a Victorian young lady. Was she embarrassed? Excited? Perhaps she entered into it with the same bold spirit seen in Shakespeare’s fictional Viola.

Siddal is seen to the far left. Her Viola leans forward, looking at Duke Orsino. Viola has disguised herself as a male page and taken the name of Cesario so that she could enter into the Duke’s service. Like Viola, Elizabeth Siddal’s wearing of Cesario’s costume helped her to enter a new world that would alter the course of her life. To the right of Orsino is the clown Feste, shown singing a song. Deverell used Dante Gabriel Rossetti as a model for Feste. In this image that marks Elizabeth Siddal’s entrance to a new world, we see one of the most famous couples in art history. Although they were probably strangers at the time Twelfth Night was painted, Rossetti and Siddal would marry a decade or so later.

William Holman Hunt also painted Elizabeth Siddal in a Shakespearean role. Unfortunately, we can no longer see her face in Valentine Rescuing Sylvia from Proteus. After critic John Ruskin described the ‘commonness of feature’ in Sylvia’s face, Hunt repainted it. We can not look to this painting as an accurate representation of Elizabeth Siddal.

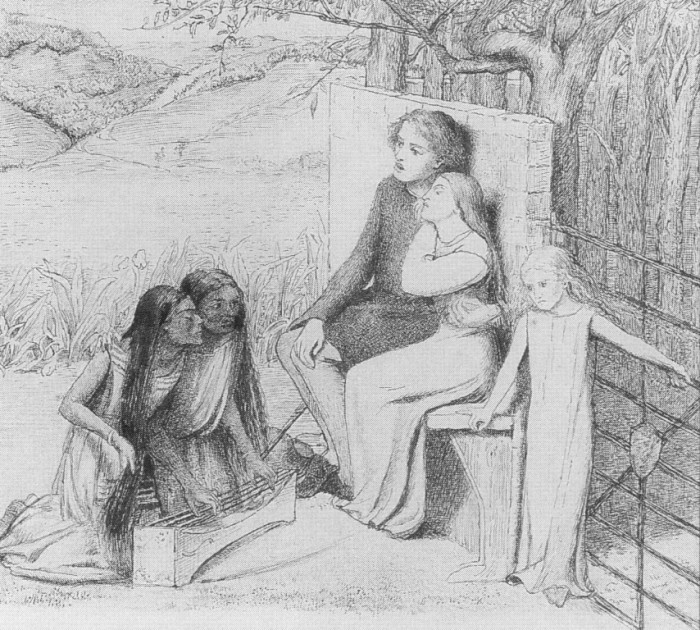

One of her first sittings for Dante Gabriel Rossetti was for his work The Return of Tibullus to Delia. Siddal sat for Delia and just as she had embraced the medieval costume of Cesario, she boldly became Delia as she posed with her hair between her lips.

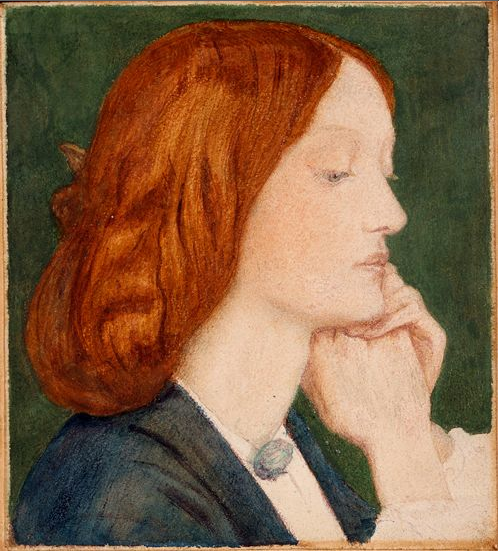

It is in the Delia studies and Millais’ study for Ophelia that I feel I get the clearest sense of Elizabeth Siddal’s visage. William Michael Rossetti wrote that Millais’ Ophelia was the painting that closest resembled his sister in law. These three studies remain among my favorite works that feature Siddal’s face.

Which brings us to what is arguably the most well-known image of Elizabeth Siddal. The tale of how she posed in a bathtub with dire consequences is told repeatedly. I think it proves how dedicated she was and speaks to her professional attitude. Once again a Shakespearean character, Siddal has become synonymous with Ophelia. Siddal’s later life was overshadowed with addiction, grief, and loss. Combine this with Millais’ famous depiction and it is easy to see why Siddal is almost always seen as an Ophelia-like figure.

Eventually, she sat only for Rossetti and the many drawings he made of her are like a private invitation into their secluded world. We see her reading, sleeping, sitting. It’s as if he had to capture her in every conceivable pose.

Ford Madox Brown wrote of Rossetti’s countless drawings of her, saying “God knows how many, but not bad work, I should say, for the six years he had known her; it is like a monomania with him. Many of them are matchless in beauty, however, and one day will be worth large sums.”

Many of Rossetti’s drawings of her depict her at work.

Where Lizzie used to be the subject, now Rossetti sat in the role of model.

We can see both Rossetti and Siddal’s features in her drawing Lovers Listening to Egyptian Girls Playing Music.

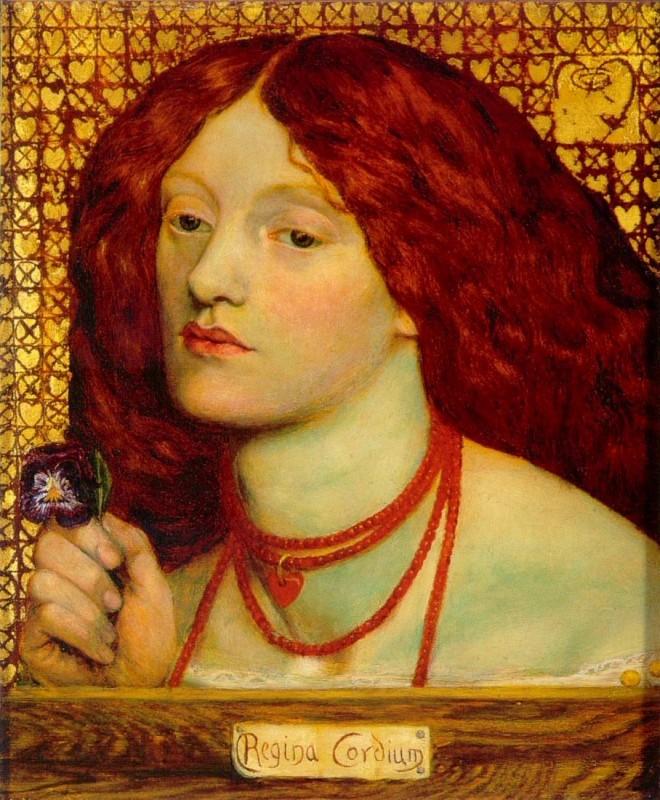

When Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Elizabeth Siddal finally married in 1860, he began this painting of her as Regina Cordium (Queen of Hearts). This work was created shortly after his painting Bocca Baciata. Both works are indicative of a new style that now characterizes his later works.

Contrast his Regina Cordium painting with his 1854 painting of Siddal.

I’d like to close this post with what I consider to be the most important image of Elizabeth Siddal. Her self-portrait.

She presents herself simply. Perhaps she wanted to move beyond the superficial and just paint the one thing that may have never been painted before: herself as she truly was. At this point, she had seen herself depicted by most of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood as Shakespearean heroines and Arthurian damsels. Now it was her turn to create the one work that sets aside all notions of Ophelia or other Pre-Raphaelite beauties. This is Elizabeth Siddal, no longer gazing off to the side as she does in Rossetti’s many drawings. Here she is before marriage, before the tragedy of her stillborn daughter. Before the cycle of addiction.

In Christina Rossetti’s poem In An Artist’s Studio, she wrote about the experience of an artist’s model who serves only as a muse and is not treasured for who she truly is. Not as she is, but as she fills his dream. I think of that line often when I look at Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s paintings of Siddal (and later, Jane Morris).

Then I look at Elizabeth Siddal’s self-portrait and think ‘Not as she is, but as she fills his dream’? Nope. Not that time.

Elizabeth Siddal’s poem, Lust of the Eyes, captures what a woman feels when loved for her beauty and nothing else. It seems fitting to end with her own words.

The Lust of the Eyes

I care not for my Lady’s soul

Though I worship before her smile;

I care not where be my Lady’s goal

When her beauty shall lose its wile.

Low sit I down at my Lady’s feet

Gazing through her wild eyes

Smiling to think how my love will fleet

When their starlike beauty dies.

I care not if my Lady pray

To our Father which is in Heaven

But for joy my heart’s quick pulses play

For to me her love is given.

Then who shall close my Lady’s eyes

And who shall fold her hands?

Will any hearken if she cries

Up to the unknown lands?

Oh, bless her for that poem! Seems like she was right to be cynical.

As a fellow Lizzie enthusiast, I just finished reading Lucinda Hawksley’s biography on Lizzie Siddal which claims that Lizzie killed herself and left a suicide note for Dante Gabriel Rosetti. I always thought that this was false and was added to her story for a bit of unnecessary and problematic embellishment. Before reading the book, I feverishly believed that Lizzie died from an accidental overdose. Lucinda Hawksley also says that the note was burned in a fire because of the stigma surrounding mental health in the 19th century. If there is no concrete evidence that she committed suicide, why is it generally believed, even in academic and well-researched texts that this is true? How do we know what really happened if there seem to be no reports saying that she did kill herself? What lead you to believe she died from an accidental overdose of laudanum? I’m not internally sure what is true and false anymore and was wondering what you had to say. Thanks!

Sorry, I meant entirely not internally.

I don’t think it is widely claimed that she committed suicide in well-researched texts by people who have studied her and/or the rest of the pre-Raphaelites specifically, though. It’s more “we can’t know, but probably not” (if I’m remembering correctly). I think the thing is that she’s the sort of person about whom dramatic and not-entirely truthful stories tend be made up, even in biographies that end up being major sources for later scholars. If you haven’t read Jan Marsh’s book, The Legend of Elizabeth Siddal, you might be interested, since it’s about what people have written about her through the century and a half(ish – the book was copyright 1989) since her death and how differently they’ve interpreted the few actual facts we know about her.

(Also, while it’s been a while, my impression of the Lucinda Hawksley biography was that it tended a little toward sensationalist, and there were a couple places where I felt like she was choosing to interpret things in the way that made Rossetti look worst.)

I like the (purportedly true) story that when she died, DGR buried all his poems in her coffin with her, but then some years later dug them up!

Lizzie was so far ahead of her time. Her talent was just beginning to bloom, I wonder what would have happened if she’d been happier with her marriage, life, health…all the unknowns and speculations. Whether it was an accident or suicide, her death robbed the world of so much. If she did kill herself, I feel uneasy trying to take that from her, that final act of self determination in a life so informed by others and their ideas of her. If she died by accident, how tragic that her life was so sad it can be easily assumed she did suicide. She was ethereal, magical, and full of promise. A legend and such an artist.