Professor Richard D. Altick is a man I never met but respect a great deal. Here in the United States, he is regarded as a pioneer of Victorian Studies. He was the author of over twenty books, including The Scholar Adventures (1950) and The Art of Literary Research (1963).

After his death at the age of 92, The Telegraph published an obituary, saying, in part:

“When he started his professional academic career the Victorian period was not a recognised field of academic study, and he himself knew next to nothing about it. This changed when he was asked to teach a course on Victorian poetry, and began a process of self-education.

By the time he moved to Ohio State University in 1946, he had acquired a passionate interest in the literature and history of Victorian England, and a taste for writing for publication. The result was a succession of books and essays that sought to promote the pleasures of literary research and to illuminate the social contexts of Victorian literature with an unprecedented richness of detail and nuance.”

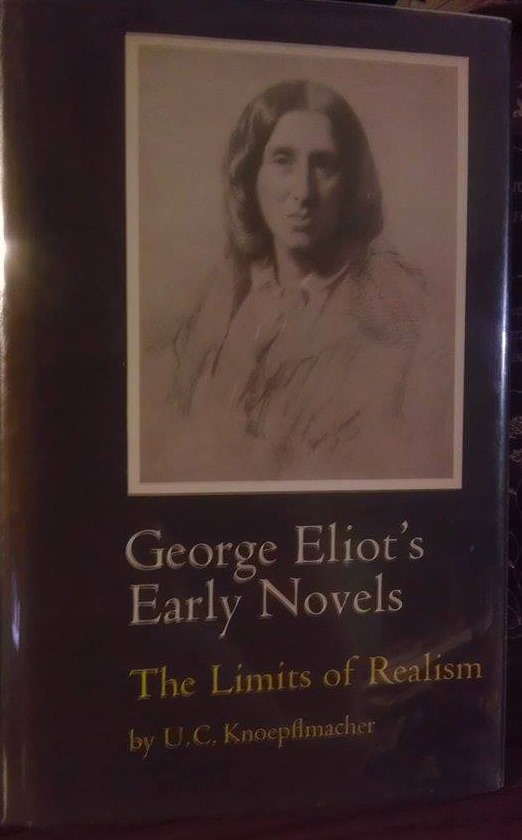

Several years after his death, I was lucky enough to purchase some of his personal books. Many of them were sent to him by publishers or newspapers that printed his reviews and, happily for me, the book dealer kept the books intact with the correspondence Professor Altick had received tucked safely inside. The book I share here, George Eliot’s Early Novels, holds my favorite letters.

In George Eliot’s Early Novels: The Limits of Realism Professor Knoepflmacher examines Eliot’s early works in order and how she ‘wrestled with the esthetic problems of reconciling her art and philosophy’. When I first received the book, I found two letters from Gene Tank, an editor at University of California Press.

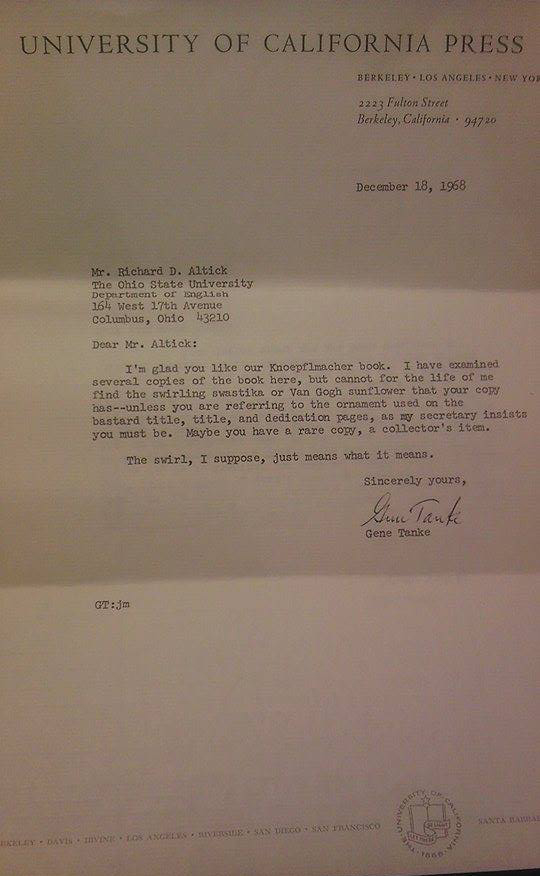

He writes to Professor Altick:

“I’m glad you like our Knoepflmacher book. I have examined several copies of the book here, but cannot for the life of me find the swirling swastika or Van Gogh sunflower that your copy has — unless you are referring to the ornament used on the bastard title, title, and dedication pages, as my secretary insists you must be. Maybe you have a rare copy, a collector’s item.

The swirl, I suppose, just means what it means.”

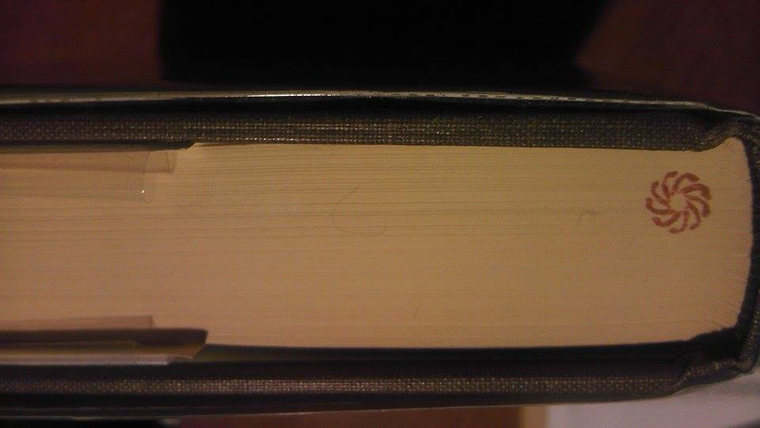

Behold, a mystery! I looked all the over the cover and the interior pages and could not find the symbol that had attracted Altick’s attention so much that he had asked Gene Tanke about it,

Luckily, there was another letter:

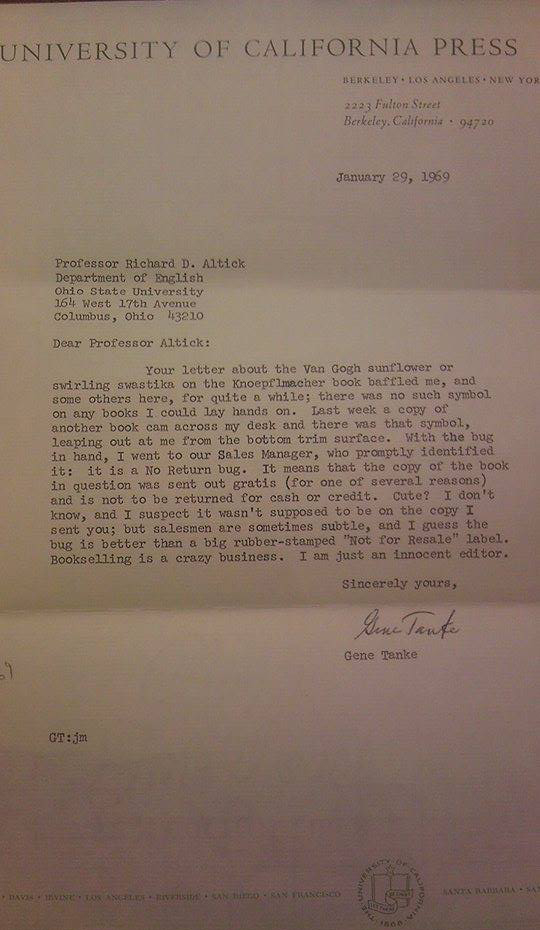

“Your letter about the Van Gogh sunflower or swirling swastika on the Knoepflmacher book baffled me, and some others here, for quite a while; there was no such symbol on any books I could lay hands on. Last week a copy of another book cam (sic) across my desk and there was that symbol, leaping out at me from the bottom trim surface. With the bug in hand, I went to our Sales Manager, who promptly identified it; it is a No Return bug. It means that the copy of the book in question was sent out gratis (for one of several reasons) and is not to be returned for cash or credit. Cute? I don’t know, and I suspect it wasn’t supposed to be on the copy I sent you; but salesmen are sometimes subtle, and I guess the bug is better than a rubber-stamped “Not for Resale” label. Bookselling is a crazy business. I am just an innocent editor.”

And there it is…