It would have been a perfect plot for a 1960s Hammer horror film: on the death of his wife, a poet places a treasured manuscript of his poems in her casket. Years later he has a new muse and love, a woman who had been a friend to them both. So he ghoulishly engineers his late wife’s exhumation so as to reclaim his final gift to her.

Upon opening the casket, his wife’s corpse is found to be in perfect condition, miraculously resisting decay for seven-and-a-half years. By some supernatural intervention, the hair that inspired him in life had continued to grow after death and has now become a huge, golden mass.

The poems are restored and published, yet the ghost of the betrayed wife will now haunt him for the rest of his life.

I can just see Elizabeth Siddal’s hair spilling out of the coffin in brilliant technicolor. It is the perfect ghost story. Except it’s not a ghost story. It’s a (mostly) true tale that has been repeated over the decades, with more macabre embellishments added with each telling until Lizzie has achieved all the makings of a Pre-Raphaelite phantom.

The morbid associations began early. There were whispered rumors that Rossetti had started Beata Beatrix by sketching his dead wife as she lay in state. Surgeon John Marshall, a friend of Rossetti’s, claimed that “for two years [Rossetti] saw her ghost every night!”

It was the age of Spiritualism, and surely Lizzie had something to say from beyond the grave. Seances were held that included both Dante Gabriel Rossetti and his brother William Michael. An unlikely medium, Rossetti’s model/mistress/housekeeper Fanny Cornforth served as a conduit for Lizzie’s messages.

After the exhumation, Rossetti wrote to Swinburne.“Had it been possible to her, I should have found the book upon my pillow the night she was buried; and could she have opened the grave no other hand would have been needed.” As if the exhumation had merely been the righting of a wrong, and they had benevolently appeased Lizzie’s restless spirit by doing what she was physically unable to do from the spiritual plane.

Everything about Lizzie is subject to exaggeration. Most people learn about her death and exhumation first and then have to work their way backwards. They come to know her through her laudanum overdose, the speculations of a disappearing suicide note and her wraith-like appearance as she stared absentmindedly into a fire, rocking the ghost of her dead child.

The hyperbole goes back even further. Her marriage is described as unhappy – Gabriel is said to be constantly adulterous, despite the fact that there is no evidence that he was unfaithful during marriage. And with the benefit of 20/20 hindsight, when she posed as Ophelia, she foreshadowed her own death.

Even the tale of her discovery as the consummate Pre-Raphaelite muse has a fairy tale quality, thanks to Holman Hunt’s account where she is described breathlessly by Deverell as “a queen.” Lizzie has become a character, a trope.

It’s worth remembering that Elizabeth Siddal wasn’t famous in her own lifetime. Although she did sell a few pieces of art and secured Ruskin’s patronage, she was unable to rise to her full potential. Her poems were never published while she lived. As a result, she is overshadowed both by the ghostly legend that surrounds her and by her husband’s fame. What we know about her is only in relation to him. The picture is not a full one, and the gaps only add to her mystery and legend.

Certainly, these cavities could have been filled had William Michael Rossetti bothered to talk to Lizzie’s mother and surviving siblings when he began to publish accounts of his brother’s life. In fact, none of the authors who wrote about Rossetti soon after his death made any effort to talk to Lizzie’s family. It seems that as the subject was mainly DGR, there was no reason to – in these accounts, Lizzie serves as a mere prop.

Her untimely death adds a certain romance; her exhumation shows the lengths Rossetti was prepared to travel for the sake of Poetry. I am reminded of the first line of Lizzie’s poem, “The Lust of the Eyes;” ‘I care not for my Lady’s soul’. We care not for Lizzie’s true self, she is seen solely as a Pre-Raphaelite figure of pathos. When Joseph Knight wrote of Lizzie’s death in his 1887 biography, Life of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, he stated that “Regina Cordium had passed forever from his life.” Again, more prop than person.

How do we lay the ghost to rest? How do we focus on Lizzie herself and set aside the macabre trappings? Focusing on her work is a good start. Her art, although unpolished, can be seen as ahead of its time. Instead of viewing her merely as Rossetti’s pupil in a one-sided exchange of teacher-to-student, we can envision their dedication to art as flowing freely and mutually between them – that they both influenced and inspired each other’s work.

Indeed, Lizzie’s contribution to the Red House murals shows that she was accepted as an artist on equal footing with her fellow PRB notables. Her letters, too, offer small glimpses into the woman she was. They’re funny and friendly – far from the thoughts of a hovering wraith. When she writes of “Mutton-chops” in her letter from Nice, we can see past Ophelia and Beatrice and see a normal woman with an enchanting sense of humor.

To pursue knowledge of her; that is the key to seeing the truth beyond the myth.

The Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood by Jan Marsh is the first book I recommend to anyone interested in the women of the Pre-Raphaelite circle. Marsh explores Lizzie’s life and the lives of her contemporaries while highlighting issues of gender, work and love. Lizzie Siddal: Face of the Pre-Raphaelites by Lucinda Hawksley is a captivating account of Lizzie’s life. In The Legend of Elizabeth Siddal, Marsh expands her work in Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood, focusing on the evolution of how we view Lizzie and how the study of her life has been approached in different eras.

The rehabilitation of Lizzie’s legacy continues. She has received renewed attention in the play Lizzie Siddal by Jeremy Green. And even though I was not completely impressed with the BBC series Desperate Romantics, I have to admit that Amy Manson portrayed Lizzie admirably.

Lizzie was recently featured in Pre-Raphaelite Sisters, the National Portrait Gallery’s first exhibition to explore the Pre-Raphaelite movement, by focusing on the women who played such crucial roles. The National Portrait Gallery exhibition also explored the Pre-Raphaelite influence found in modern works, such as Tom Beard’s haunting photograph of musician Florence Welch.

I am deeply honored that our Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood site was quoted by curator Alison Smith in her essay, The Sisterhood and Its Afterlife, that appeared in the exhibition’s stunning catalogue.

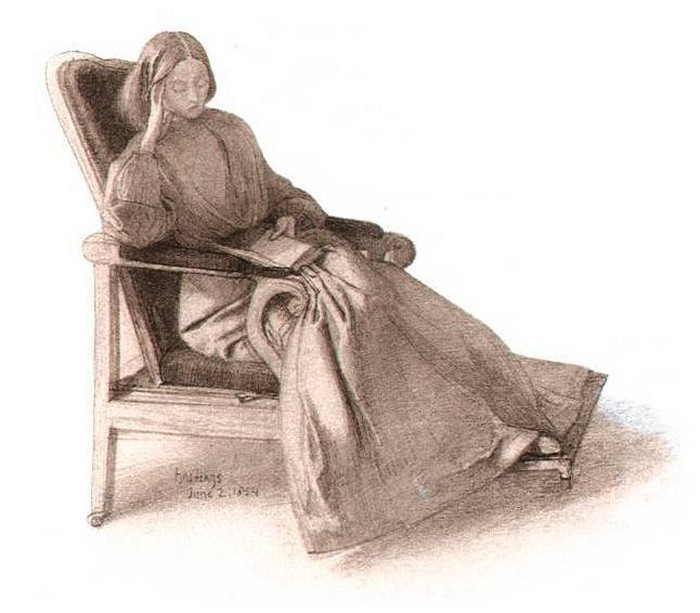

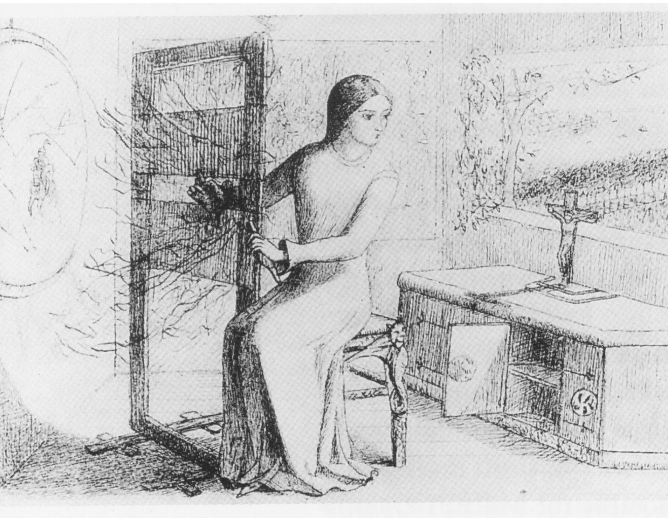

Lizzie Siddal is ever-emerging from the spectral fog and beginning to shed her ghostly stigma. We have image after image of Lizzie appearing languid and reclining, but we also have images of her hard at work, sitting at easels, determined to hone her craft.

On the anniversary of Elizabeth Siddal’s death, I prefer to focus on these depictions of this remarkable, but often misunderstood, woman.