Pre-Raphaelite art is known for its exquisite luminosity – but how was this effect achieved? Why was it so radical at the time?

The Status Quo

In the early nineteenth century, the majority of work produced by British artists consisted of darkly-colored paintings – partly because of their reverence for seventeenth century masterpieces, but also due to the frequent use of bitumen, a tarry additive that creates a blackening effect, and further darkens over time.

Let’s take a look at a couple of examples of this type of bitumen-derived darkness that the Pre-Raphaelites rebelled against.

Both paintings are classic and compelling works, but it’s easy to see why the Pre-Raphaelites were so driven to create art that practically bursts with brightness. When all the art surrounding you feels somber, how could you not long to create art with vibrant and intense pigments?

The Pre-Raphaelites were not the first nineteenth century artists to embrace a lighter tone. J.M.W. Turner displayed an impressive use of glowing light in his later works, and artist William Mulready was painting his works over a thin white ground two decades before the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood formed in 1848.

Despite occasional forays into expressions of light and color by artists like Turner and Mulready, earthy tones remained the norm, as did the belief that a painting should adhere to the Royal Academy’s unwritten edict: one area of principal light, with everything surrounding it swathed in some degree of shadow.

Enter the Brotherhood

The art world resembled a morose cauldron of bitumen to the seven young upstarts that formed the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. They were champing at the bit to inject effervescent light and color onto the scene.

When the brotherhood formed, they were committed to embracing colors and techniques seen in works before the artist Raphael (1483-1520), as well as depicting nature in its true form.

The results were nothing short of revolutionary.

Despite its unwieldy title, A Converted British Family Sheltering a Christian Missionary from the Persecution of the Druids by William Holman Hunt is breathtakingly vivid in light, color, and detail – especially when viewed in conjunction with the darker-toned works that that had long been the status quo.

How Did They Do It?

In his memoir, Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, William Holman Hunt described the process he and his Pre-Raphaelite brethren used to obtain their startling luminosity. This entailed a wet, white ground and is quite complex in comparison to the thin white ground used previously by artist William Mulready.

“The process may be described thus. Select a prepared ground originally for its brightness, and renovate it, if necessary, with fresh white when first it comes into the studio, white to be mixed with a very little amber or copal varnish. Let this last coat become of thoroughly stone-like hardness. Upon this surface, complete with exactness the outline in part in hand. On the morning for the painting, with fresh white (from which all superfluous oil has been extracted by means of absorbent paper, and to which again a small drop of varnish has been added) spread a further coat very evenly with a palette knife over the part for the day’s work, of such consistency that the drawing should faintly show through. In some cases the thickened white may be applied to the forms needing brilliancy with a brush, by the aid of rectified spirits. Over this wet ground, the color (transparent and semi-transparent) should be laid with light sable brushes, and the touches must be made so tenderly that the ground below shall not be worked up, yet so far enticed blend with the superimposed tints as to correct the qualities of thinness and staininess, which over a dry ground transparent colors used would inevitably exhibit. Painting of this kind cannot be retouched except with an entire loss of luminosity.”

William Holman Hunt, Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

The Brotherhood’s innovative new white base provided a reflective background, creating not only intense color, but brilliant illumination.

Many critics found the radical new sense of balance in the PRB’s work jarring. It was shocking for a painting not to have at least some area of the piece cloaked in shadow.

Pre-Raphaelite artists also considered a painting’s background as important as the foreground, sparing no attention to detail. Both of these factors produced a sense of hyperrealism that the British public had never seen before.

An Inspiration for Their Innovation?

During a recent visit to the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, one room in particular completely captivated me: their collection of 14th and 15th-century stained glass.

It’s a dimly lit room, of course, so that these gorgeous antiquities can be shown to perfection, and the lighting creates a sacred feeling of awe. The windows are backlit so that they can be experienced as originally intended.

My first feelings were reverent, mindful of the fact that these windows carry a wealth of significance and originally adorned places of worship where the majority of the congregation could not read. A large part of the congregants’ knowledge of scripture came from what was read to them and what they saw in art like this – the windows that surrounded them, enveloping them with jeweled light and stunning, inspiring images.

The mere notion of the untold number of prayers that have been uttered in the presence of these windows touched my heart.

My second thoughts were of the Pre-Raphaelites. Inspired by the exquisite backlit presentation of each stained glass, a fresh notion occurred to me – I was able to think of the Pre-Raphaelite painting process in a deeper way.

For example…

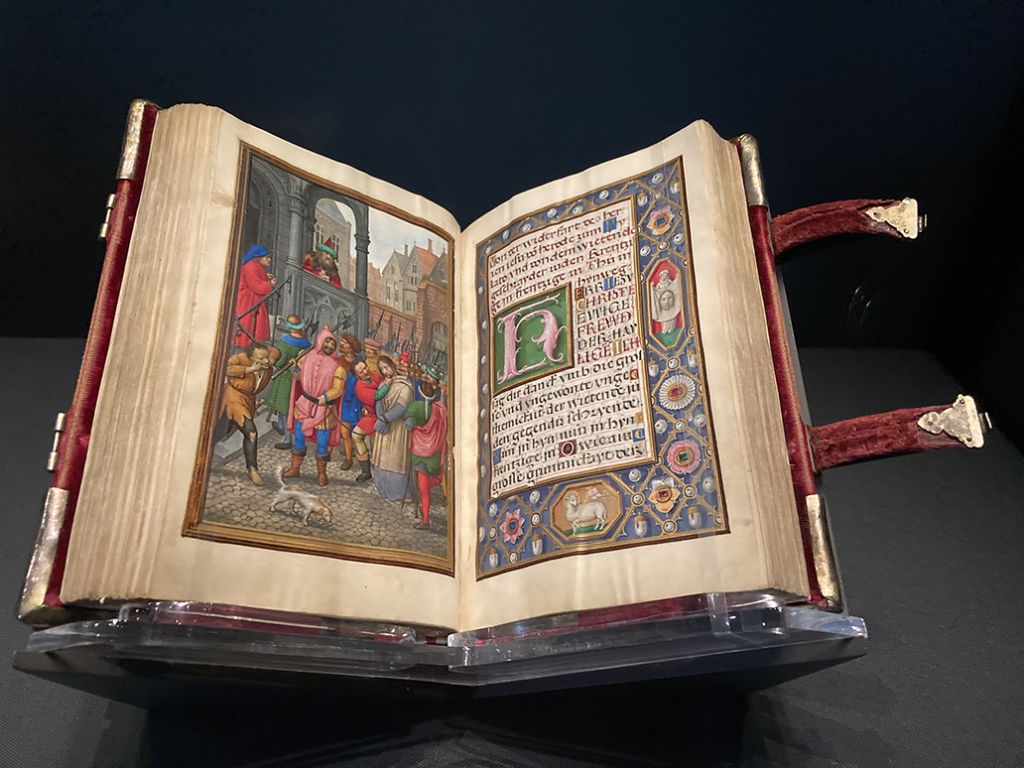

This a collection of roundels on display at the Getty. Dating to the early 1500s, each one is delicately illustrated with astonishing craftsmanship.

The center roundel in the Getty’s display is an image of the crucifixion. The image on the left is as it appears in the museum, illuminated from behind.

To see it without backlighting would be a far less inspiring experience, and I imagine it would be similar to the image on the right, shared from the Getty’s website (an image of the reverse side to show it in its pre-conservation state). Still beautiful, but far less alive than the fully lit window.

Did the Pre-Raphaelites Take a Cue From Stained Glass and Manuscripts of the Past?

Fascinated by medieval and renaissance art, the Pre-Raphaelites were quite familiar with early Christian art, especially illuminated manuscripts and stained glass. They were enchanted by the distinctive style of that era, which may be one reason why so much of the PRB’s early works were religious in nature.

In contrast to the muddy brown art of the early to mid-nineteenth century, I believe the Pre-Raphaelites channeled the principle of stained glass into their creations, using their wet white ground as a sort of pseudo-illumination.

The luminous quality of a Pre-Raphaelite painting is not simply due to the prismatic colors the artists used. Like stained glass, it’s all about the light source, and though theirs is artificial, it works – stunningly so.

Appreciating Victorian art with my twenty-first century eyes, I can completely understand why critics had such a reflexively adverse reaction to the astonishing harmony of color and light the Pre-Raphaelites brought to the scene.

Change is often uncomfortable to absorb. The PRB and their associates ushered in a new period of art – almost as suddenly as Dorothy opening her sepia-colored door onto the technicolor world of Oz.

Pre-Raphaelite art is a bit like a successful recipe, with each essential ingredient contributing to the piece de resistance. The subject matter, the symbolism, and the detailed precision are all important elements. Subtract the incandescent sense of light and color, and the Pre-Raphaelites’ work would have lost the essence of its unique flavor.

In their ingenious pursuit of truth and how to express it, the Brotherhood revived art with an emotional intensity, energy and sense of wonder that still inspires.

So interesting to find out how the Pre-Raphaelites worked;-) thank you Stephanie!

I really enjoyed reading this, thank you!

Who painted the first image – the Convent Thoughts? It is stunning!

Hi! Convent Thoughts was painted by Charles Allston Collins, brother of Victorian writer Wilkie Collins (The Woman in White). It’s absolutely gorgeous.

And IIRC it’s in the Ashmolean Musuem in Oxford (UK)

Intreasting

I adore waterhouse there were women painters too who were part of the clan.

I studied the fallen women as part of my BA in art history .

I think thats were the Pre Raphaelites really questioned the political state that women were being judged