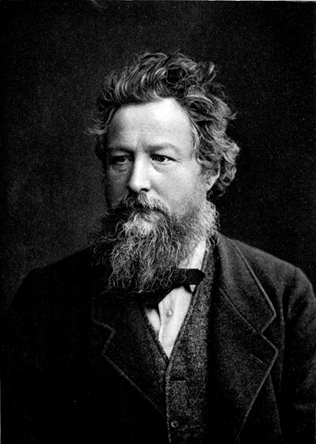

Since finishing Le Morte d’Arthur, I’ve been refreshing my memory and reading all the references I can find regarding Pre-Raphaelite art and Arthurian influences. My first choice was a William Morris biography that I happily stumbled across at a flea market a few years ago. There’s one paragraph in particular that always stands out to me, partly because it’s so much fun to imagine William Morris as a child:

“Medievalism was not a new discovery in his adolescence. He had read Scott’s novels before he was seven: he had ridden the glades of Epping Forest in a toy suit of armour. From his childhood his eye and visual memory were sharp for the architecture and art of the Middle Ages: and his games were those of knights, barons and fairies.” (E.P. Thompson)

I’d like to find more references that mention Morris and his childhood suit of armor. Please contact me if you know of one. I did find this mention (via Google books) in a book called English lyrical poetry from its origins to the present time by Edward Bliss Reed: “William Morris (1834-1896) “poet, artist, manufacturer, and socialist”, felt from childhood the fascination of the Middle Ages. He delighted to visit the old churches about his Essex home, making rubbings from the inscriptions on their tombs or studying their carvings. There is a certain period in the life of every boy when he must have his soldier suit; Morris, true to his tastes, had a suit of armor.”

It’s that image of young William romping around in a suit of armor that gets me. Absolutely endearing. It’s also wonderful to learn that a passion for all things medieval is not just an interest that developed in his adulthood, he embraced it all of his life.

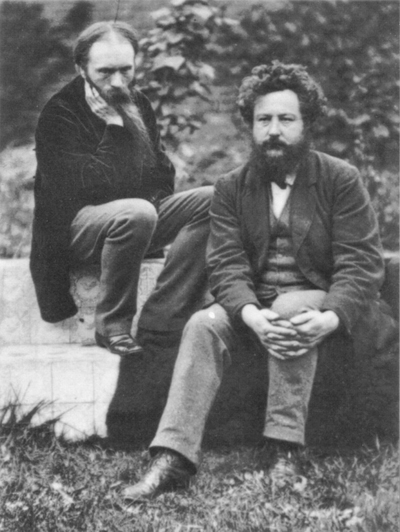

In his friend Edward (Ned) Burne-Jones, he found a kindred spirit. Both had a love of Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur, with its tales of enchantment and chivalry:

“Morris and Burne-Jones, while undergraduates at Oxford, spent much time reading and discussing the copy of Le Morte d’Arthur which Morris had bought for them both, because the impecunious Burne-Jones could not afford it.” (The Return of King Arthur, Beverly Taylor and Elisabeth Brewer) I love that sentence, and not only because of the word impecunious. I just like the thought of Morris and Burne-Jones (Topsy and Ned) as undergraduates, sitting together in serious discussion of a work that inspired them. They were young, eager, and idealistic. Perhaps I am romanticizing it, but I like the image that comes to mind of close quarters and intense conversation, perhaps with a roaring fire in the background. It reminds me of the beginning of Morris’ short story A Dream. “I dreamed once, that four men sat by the winter fire talking and telling tales, in a house that the wind howled round.” Yes, I say. Let’s sit close to the fire and discuss and ponder. Let’s tell tales while a wind howls outside. Couldn’t it have been like that for Morris and Burne-Jones?

By the way, on the subject of Morris and Burne-Jones, you should take a look at this wonderful “Ned and Topsy” T-shirt, designed by Raine Szramski.

When we mention Morris and Le Morte d’Arthur, it is usually Morris’s work The Defence of Guenevere that comes to mind. And it certainly should. The poem is interesting and unusual in that it was bold for Morris to write from the standpoint of defending Guenevere, who had been untrue to Arthur. I like Morris’ poems. Dante Gabriel Rossetti once wrote to poet William Allingham that “Morris’s facility for poeticizing puts one in a rage.” It was at the beginning of Morris’s poetic endeavors and Rossetti went on to say “He has been writing at all for little more than a year, I believe, and has already poetry enough for a big book.” The Defence of Guenevere appears below. You may also want to read Fluid Gender Roles in “The Defence of Guenevere”and The Medievalism and Modernity of “The Defence of Guenevere”, both from The Victorian Web.

Jane Burden is the model for this painting by Morris, called by many Queen Guenevere although later it was referred to as La Belle Iseult. Jane Morris, according to Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood by Jan Marsh, confirmed the Iseult title in later years. I should add that Jan Marsh’s Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood is not associated with this site. But it is a wonderful book and I highly recommend it.

The Defence of Guenevere

But, knowing now that they would have her speak,

She threw her wet hair backward from her brow,

Her hand close to her mouth touching her cheek,

As though she had had there a shameful blow,

And feeling it shameful to feel ought but shame

All through her heart, yet felt her cheek burned so,

She must a little touch it; like one lame

She walked away from Gauwaine, with her head

Still lifted up; and on her cheek of flame

The tears dried quick; she stopped at last and said:

“O knights and lords, it seems but little skill

To talk of well-known things past now and dead.

“God wot I ought to say, I have done ill,

And pray you all forgiveness heartily!

Because you must be right, such great lords; still

“Listen, suppose your time were come to die,

And you were quite alone and very weak;

Yea, laid a dying while very mightily

“The wind was ruffling up the narrow streak

Of river through your broad lands running well:

Suppose a hush should come, then some one speak:

“‘One of these cloths is heaven, and one is hell,

Now choose one cloth for ever; which they be,

I will not tell you, you must somehow tell

“‘Of your own strength and mightiness; here, see!’

Yea, yea, my lord, and you to ope your eyes,

At foot of your familiar bed to see

“A great God’s angel standing, with such dyes,

Not known on earth, on his great wings, and hands,

Held out two ways, light from the inner skies

“Showing him well, and making his commands

Seem to be God’s commands, moreover, too,

Holding within his hands the cloths on wands;

“And one of these strange choosing cloths was blue,

Wavy and long, and one cut short and red;

No man could tell the better of the two.

“After a shivering half-hour you said:

‘God help! heaven’s colour, the blue;’ and he said, ‘hell.’

Perhaps you then would roll upon your bed,

“And cry to all good men that loved you well,

‘Ah Christ! if only I had known, known, known;’

Launcelot went away, then I could tell,

“Like wisest man how all things would be, moan,

And roll and hurt myself, and long to die,

And yet fear much to die for what was sown.<!–more–>

“Nevertheless you, O Sir Gauwaine, lie,

Whatever may have happened through these years,

God knows I speak truth, saying that you lie.”

Her voice was low at first, being full of tears,

But as it cleared, it grew full loud and shrill,

Growing a windy shriek in all men’s ears,

A ringing in their startled brains, until

She said that Gauwaine lied, then her voice sunk,

And her great eyes began again to fill,

Though still she stood right up, and never shrunk,

But spoke on bravely, glorious lady fair!

Whatever tears her full lips may have drunk,

She stood, and seemed to think, and wrung her hair,

Spoke out at last with no more trace of shame,

With passionate twisting of her body there:

“It chanced upon a day that Launcelot came

To dwell at Arthur’s court: at Christmas-time

This happened; when the heralds sung his name,

“Son of King Ban of Benwick, seemed to chime

Along with all the bells that rang that day,

O’er the white roofs, with little change of rhyme.

“Christmas and whitened winter passed away,

And over me the April sunshine came,

Made very awful with black hail-clouds, yea

“And in the Summer I grew white with flame,

And bowed my head down: Autumn, and the sick

Sure knowledge things would never be the same,

“However often Spring might be most thick

Of blossoms and buds, smote on me, and I grew

Careless of most things, let the clock tick, tick,

“To my unhappy pulse, that beat right through

My eager body; while I laughed out loud,

And let my lips curl up at false or true,

“Seemed cold and shallow without any cloud.

Behold my judges, then the cloths were brought;

While I was dizzied thus, old thoughts would crowd,

“Belonging to the time ere I was bought

By Arthur’s great name and his little love;

Must I give up for ever then, I thought,

“That which I deemed would ever round me move

Glorifying all things; for a little word,

Scarce ever meant at all, must I now prove

“Stone-cold for ever? Pray you, does the Lord

Will that all folks should be quite happy and good?

I love God now a little, if this cord

“Were broken, once for all what striving could

Make me love anything in earth or heaven?

So day by day it grew, as if one should

“Slip slowly down some path worn smooth and even,

Down to a cool sea on a summer day;

Yet still in slipping there was some small leaven

“Of stretched hands catching small stones by the way,

Until one surely reached the sea at last,

And felt strange new joy as the worn head lay

“Back, with the hair like sea-weed; yea all past

Sweat of the forehead, dryness of the lips,

Washed utterly out by the dear waves o’ercast,

“In the lone sea, far off from any ships!

Do I not know now of a day in Spring?

No minute of the wild day ever slips

“From out my memory; I hear thrushes sing,

And wheresoever I may be, straightway

Thoughts of it all come up with most fresh sting:

“I was half mad with beauty on that day,

And went without my ladies all alone,

In a quiet garden walled round every way;

“I was right joyful of that wall of stone,

That shut the flowers and trees up with the sky,

And trebled all the beauty: to the bone,

“Yea right through to my heart, grown very shy

With weary thoughts, it pierced, and made me glad;

Exceedingly glad, and I knew verily,

“A little thing just then had made me mad;

I dared not think, as I was wont to do,

Sometimes, upon my beauty; if I had

“Held out my long hand up against the blue,

And, looking on the tenderly darken’d fingers,

Thought that by rights one ought to see quite through,

“There, see you, where the soft still light yet lingers,

Round by the edges; what should I have done,

If this had joined with yellow spotted singers,

“And startling green drawn upward by the sun?

But shouting, loosed out, see now! all my hair,

And trancedly stood watching the west wind run

“With faintest half-heard breathing sound: why there

I lose my head e’en now in doing this;

But shortly listen: In that garden fair

“Came Launcelot walking; this is true, the kiss

Wherewith we kissed in meeting that spring day,

I scarce dare talk of the remember’d bliss,

“When both our mouths went wandering in one way,

And aching sorely, met among the leaves;

Our hands being left behind strained far away.

“Never within a yard of my bright sleeves

Had Launcelot come before: and now so nigh!

After that day why is it Guenevere grieves?

“Nevertheless you, O Sir Gauwaine, lie,

Whatever happened on through all those years,

God knows I speak truth, saying that you lie.

“Being such a lady could I weep these tears

If this were true? A great queen such as I

Having sinn’d this way, straight her conscience sears;

“And afterwards she liveth hatefully,

Slaying and poisoning, certes never weeps:

Gauwaine be friends now, speak me lovingly.

“Do I not see how God’s dear pity creeps

All through your frame, and trembles in your mouth?

Remember in what grave your mother sleeps,

“Buried in some place far down in the south,

Men are forgetting as I speak to you;

By her head sever’d in that awful drouth

“Of pity that drew Agravaine’s fell blow,

I pray you pity! let me not scream out

For ever after, when the shrill winds blow

“Through half your castle-locks! let me not shout

For ever after in the winter night

When you ride out alone! in battle-rout

“Let not my rusting tears make your sword light!

Ah! God of mercy, how he turns away!

So, ever must I dress me to the fight,

“So: let God’s justice work! Gauwaine, I say,

See me hew down your proofs: yea all men know

Even as you said how Mellyagraunce one day,

“One bitter day in la Fausse Garde, for so

All good knights held it after, saw:

Yea, sirs, by cursed unknightly outrage; though

“You, Gauwaine, held his word without a flaw,

This Mellyagraunce saw blood upon my bed:

Whose blood then pray you? is there any law

“To make a queen say why some spots of red

Lie on her coverlet? or will you say:

‘Your hands are white, lady, as when you wed,

“‘Where did you bleed?’ and must I stammer out, ‘Nay,

I blush indeed, fair lord, only to rend

My sleeve up to my shoulder, where there lay

“‘A knife-point last night’: so must I defend

The honour of the Lady Guenevere?

Not so, fair lords, even if the world should end

“This very day, and you were judges here

Instead of God. Did you see Mellyagraunce

When Launcelot stood by him? what white fear

“Curdled his blood, and how his teeth did dance,

His side sink in? as my knight cried and said:

‘Slayer of unarm’d men, here is a chance!

“‘Setter of traps, I pray you guard your head,

By God I am so glad to fight with you,

Stripper of ladies, that my hand feels lead

“‘For driving weight; hurrah now! draw and do,

For all my wounds are moving in my breast,

And I am getting mad with waiting so.’

“He struck his hands together o’er the beast,

Who fell down flat, and grovell’d at his feet,

And groan’d at being slain so young: ‘At least,’

“My knight said, ‘rise you, sir, who are so fleet

At catching ladies, half-arm’d will I fight,

My left side all uncovered!’ then I weet,

“Up sprang Sir Mellyagraunce with great delight

Upon his knave’s face; not until just then

Did I quite hate him, as I saw my knight

“Along the lists look to my stake and pen

With such a joyous smile, it made me sigh

From agony beneath my waist-chain, when

“The fight began, and to me they drew nigh;

Ever Sir Launcelot kept him on the right,

And traversed warily, and ever high

“And fast leapt caitiff’s sword, until my knight

Sudden threw up his sword to his left hand,

Caught it, and swung it; that was all the fight,

“Except a spout of blood on the hot land;

For it was hottest summer; and I know

I wonder’d how the fire, while I should stand,

“And burn, against the heat, would quiver so,

Yards above my head; thus these matters went;

Which things were only warnings of the woe

“That fell on me. Yet Mellyagraunce was shent,

For Mellyagraunce had fought against the Lord;

Therefore, my lords, take heed lest you be blent

“With all this wickedness; say no rash word

Against me, being so beautiful; my eyes,

Wept all away to grey, may bring some sword

“To drown you in your blood; see my breast rise,

Like waves of purple sea, as here I stand;

And how my arms are moved in wonderful wise,

“Yea also at my full heart’s strong command,

See through my long throat how the words go up

In ripples to my mouth; how in my hand

“The shadow lies like wine within a cup

Of marvellously colour’d gold; yea now

This little wind is rising, look you up,

“And wonder how the light is falling so

Within my moving tresses: will you dare,

When you have looked a little on my brow,

“To say this thing is vile? or will you care

For any plausible lies of cunning woof,

When you can see my face with no lie there

“For ever? am I not a gracious proof:

‘But in your chamber Launcelot was found’:

Is there a good knight then would stand aloof,

“When a queen says with gentle queenly sound:

‘O true as steel come now and talk with me,

I love to see your step upon the ground

“‘Unwavering, also well I love to see

That gracious smile light up your face, and hear

Your wonderful words, that all mean verily

“‘The thing they seem to mean: good friend, so dear

To me in everything, come here to-night,

Or else the hours will pass most dull and drear;

“‘If you come not, I fear this time I might

Get thinking over much of times gone by,

When I was young, and green hope was in sight:

“‘For no man cares now to know why I sigh;

And no man comes to sing me pleasant songs,

Nor any brings me the sweet flowers that lie

“‘So thick in the gardens; therefore one so longs

To see you, Launcelot; that we may be

Like children once again, free from all wrongs

“‘Just for one night.’ Did he not come to me?

What thing could keep true Launcelot away

If I said, ‘Come’? there was one less than three

“In my quiet room that night, and we were gay;

Till sudden I rose up, weak, pale, and sick,

Because a bawling broke our dream up, yea

“I looked at Launcelot’s face and could not speak,

For he looked helpless too, for a little while;

Then I remember how I tried to shriek,

“And could not, but fell down; from tile to tile

The stones they threw up rattled o’er my head

And made me dizzier; till within a while

“My maids were all about me, and my head

On Launcelot’s breast was being soothed away

From its white chattering, until Launcelot said:

“By God! I will not tell you more to-day,

Judge any way you will: what matters it?

You know quite well the story of that fray,

“How Launcelot still’d their bawling, the mad fit

That caught up Gauwaine: all, all, verily,

But just that which would save me; these things flit.

“Nevertheless you, O Sir Gauwaine, lie,

Whatever may have happen’d these long years,

God knows I speak truth, saying that you lie!

“All I have said is truth, by Christ’s dear tears.”

She would not speak another word, but stood

Turn’d sideways; listening, like a man who hears

His brother’s trumpet sounding through the wood

Of his foes’ lances. She lean’d eagerly,

And gave a slight spring sometimes, as she could

At last hear something really; joyfully

Her cheek grew crimson, as the headlong speed

Of the roan charger drew all men to see,

The knight who came was Launcelot at good need.

I really enjoyed this post. I love William Morris. Thanks.

Thank you! That means a lot to me.

I have nothing worthwhile to add, just that I LOVE YOUR SITE SO MUCH! And I just read on your about page what you said about ‘not being a scholar’ and I just want to tell you that when I read this site I can see how much you put into it and how much you love it.

I read a similar passage about “Mini Morris” riding a pony about the countryside, dressed in armor – I’ll see if I can find the exact reference (and it will bug me until I do). It thrilled me as I’ve long been lover of the Waverly Novels, having read them as a teen and it mentioned them specifically as your reference does.

A similar passage appears in “William Morris: Artist Craftsman Pioneer” by R. Ormiston & N.M. Wells

“He was an intelligent young boy, always reading but restlessly turning from one book to or one interest to another. He readily absorbed information and literature, and it is said that he had read all of Walter Scott’s Waverly novels by the age of seven. He was boisterous and given to fits of temper, but read and wrote and endless stream of chivalric romances and fairy stories. His obsession with knights and fair ladies, elves and fairies provide an early indication of his more romantic preoccupations.”

Thank you Lisa! Love the image of him ‘always reading, but restlessly turning from one book or one interest to another’.

I wonder if for Morris anyway (BJ was not keen on them at all ) the Icelandic sagas had the same type of mythology as the Arthurian legends.

Wonderful post. This is why I love William Morris. <3

Hi this is a subject close to my heart. My undergraduate dissertation explored the reinvention of Arthurian myth in Victorian literature and art, with particular emphasis on William Morris’ Defence of Guenevere and Tennyson’s Idylls of the King. You may like to compare the two poems which highlight Morris’ radical, “modern” views on women and gender opposed to Tennyson’s more conservative reactionary treatment of Guenevere. Has anyone ever visited Red House in Bexley Heath, Kent? I went there last year as I live a few miles away and it was an amazing, evocative experience. You could really imagine Morris, Janey, Rosetti, the Burne-Jones’ sitting outside dressed in full medieval regalia. The guide said this was a regular occurrence with May and Jenny also part of their re-enactments.

Thanks so much for your comment. When I was reading Le Morte d’Arthur, I kept hearing echoes of Tennyson in my head and sort of mentally comparing the two. Tennyson’s Arthurian works are highly moralized in comparison. I prefer Morris’s take on Guenevere.

Although my Comment is not strictly, or even spiritually, directly connected with the Pre-Raphaelites (sisterhood, brotherhood or other!) I much enjoyed straying into the wide conversation above, by myself using Keats’ “palely loitering” in an article I wrote today in my column: One Man’s Week, published in Uganda’s New Vision newspaper of 11 August 2018. I had quickly looked in my computer to see who had ever written an answer to Shakespeare’s “To be or not to be…” soliloquy in Hamlet, but in my haste not found anything. (Should this be ultimately true, I am laying a claim!!) By the way, the title for this week’s column is “An Answer to a Conundrum”, in my series, which has now run for a couple of decades, and some of which might come out soon in a couple of volumes.