Sir John Everett Millais’ painting The Woodman’s Daughter is based on a poem by Coventry Patmore. When first exhibited in 1851, this excerpt of the poem accompanied the work:

She went merely to think she help’d;

And, whilst he hack’d and saw’d,

The rich Squire’s son, a young boy then,

Whole mornings, as if awed,

Stood silent by, and gazed in turn

At Gerald and on Maud.

He sometimes, in a sullen tone

He offer’d fruits, and she Received them always with an air

So unreserved and free,

That shame-faced distance soon became

Familiarity. (full poem here.)

Pre-Raphaelite artists often drew upon poetry and literature for their subject matter, demonstrating how strongly visual art can be linked with the written word. Patmore’s poem tells the story of a woodman and his daughter, who accompanies her father at work. A squire’s son, wealthy and from a higher social class, watches them and offers the girl fruit. This leads to a long friendship and the pair grow up together. She later succumbs to his advances, bearing an illegitimate child. Their difference in social class means that marriage is an impossibility and she kills the infant and goes mad. Millais depicts them at the moment their acquaintance begins, with the offering of fruit, a moment that can be seen as foreshadowing their later romantic entanglement. With the offering of strawberries, Millais shows the exact point in time that will lead to her downfall.

The artist’s son, John Guille Millais, described the painting as ‘truly Pre-Raphaelite’:

“Of all the pictures ever painted, there is probably none more truly Pre-Raphaelite than one I have already mentioned — “The Woodsman’s Daughter”. It was painted in 1850 in a wood near Oxford, and was exhibited in 1851. Every blade of grass, every leaf and branch, and every shadow that they cast in the sunny wood is presented here with unflinching realism and infinite delicacy of detail. Yet the figures are in no way swamped by their surroundings, every accessory taking its proper place, in subordination to the figures and the tale they have to tell. ” –The Life and Letters of Sir John Everett Millais, Vol. I

I find the ending of Patmore’s poem haunting. It’s beautifully written yet devastating.

The moon, now gleaming sharp and bright,

From the small cloud slumbering nigh;

And, one by one, the timid stars

Step out into the sky.

The night blackens the pool, but Maud

Is constant at her post,

Sunk in a dread, unnatural sleep.

Beneath the skiey host

Of drifting mists, thro’ which the moon

Is riding like a ghost.

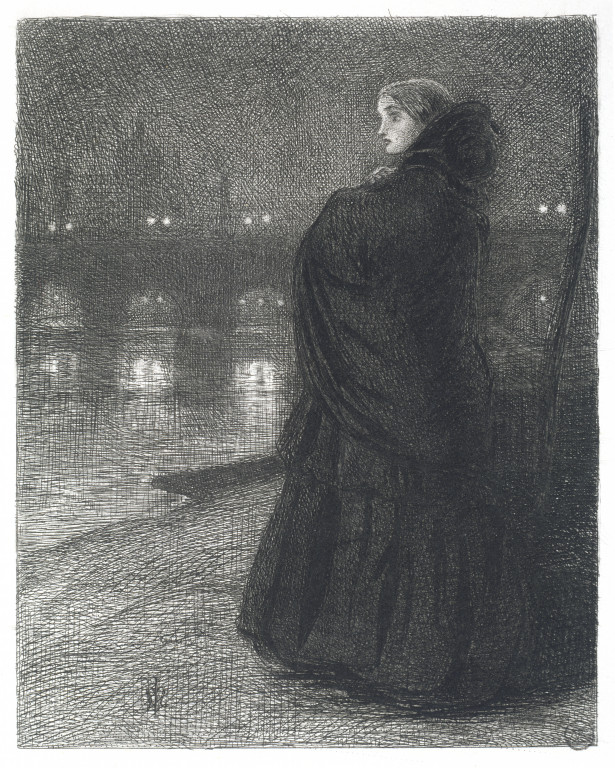

The Woodman’s Daughter is not the only time Millais tackled the issue of an unplanned pregnancy ending in tragedy. The Bridge of Sighs is delicate, full of pathos, and represents the plight of any young woman in the Victorian era who has been unfortunate enough to lose her virtue. Both works bring to mind the double standard that persists in many cultures to this day: no one seems to mourn a male who loses his virtue, yet a female with a past is forever tainted.

Based on the poem by Thomas Hood, The Bridge of Sighs describes a young woman who commits suicide by plunging to her death from Waterloo Bridge. The poem hints that the woman was thrown out of her home due to an illegitimate pregnancy, a common occurrence that was severely frowned upon by Victorian society. Such a pregnancy was seen as a disgrace to an entire family and often parents felt that there was no other choice than to shun their daughter and cut off contact completely.

To be an unwed mother was a fate worse than death, as cliche as that sounds. Had she lived to give birth to her child, she faced destitution and life as a social pariah. However, her death in the poem restores both her beauty and innocence, as we see in this passage:

Make no deep scrutiny

Into her mutiny

Rash and undutiful:

Past all dishonour,

Death has left on her

Only the beautiful.

Sadly, a death such as this is not seen only in poems and fiction. Reports of young womens’ bodies found drowned were common in newspapers of the time, which seems to have been a source of inspiration for G.F. Watts’ painting Found Drowned.

In Found Drowned, Watts shows the deceased woman under Waterloo Bridge, her legs still dangling in the Thames. A locket rests in her hand. Although the city in the background is partially masked by fog, a single bright star can be seen in the sky. One cannot help but stare at her lifeless body and outstretched arms. Although intended for a Victorian audience, we should still feel deep empathy in Watts’ subject. This is such a waste. That a society could be so structured and so rigid that those who in the most need of help and compassion felt that their only recourse was death.

In she plunged boldly—

No matter how coldly

The rough river ran—

Over the brink of it,

Picture it—think of it,

Dissolute Man!

Lave in it, drink of it,

Then, if you can!Take her up tenderly,

Lift her with care;

Fashion’d so slenderly,

Young, and so fair!