La Belle Dame sans Merci translated from the French means “the beautiful lady without pity” or “the beautiful lady without mercy”. It is possible that the poem is based on the ballad of ‘True Thomas’, also known as ‘Thomas the Rhymer’, which tells how a man was enchanted by the queen of Elfland and lured to her home, where he had to serve her for seven years. If Keats did indeed base his poem on the ‘True Thomas’ ballad, he takes up that story after the seven years are over and the spell is no longer binding.

It’s a beautiful poem that is full of romantic language and embodies the folk-lore theme of the Fairy Lover. I met a lady in the meads,/Full beautiful–a faery’s child;/Her hair was long, her foot was light,/And her eyes were wild. The word ‘wild’ is repeated three times in the poem, possibly an indication that the beautiful lady in the meads cannot and will not be tamed. Beware of wild animals.

Keats uses two speakers: the first is the anonymous narrator who spies the knight ‘alone and palely loitering’ in a barren landscape where ‘no birds sing’. He sets the tone of the knight’s suffering, letting us know how haggard and woe-begone he is. The next speaker is the knight, who tells how he met the enchantress in the meads. Struck by her beauty, he sets her on his steed and she sings a faery song, thus beginning her spell. They spend the afternoon together while he adorns her with floral garlands and bracelets. She draws him in further as “She looked at me as she did love,/And made sweet moan. But she does not love. Not of the mortal world, she captivates and ensnares. When she takes the knight to her elfin grot, he sees visions in his sleep of pale kings, princes and warriors — her previous conquests who warn him that “La belle Dame sans Merci hath thee in thrall!”

The knight, who we can assume was once vibrant and strong, has been abandoned by his faery love and now wanders a desolate landscape. Is the poem a warning about hopeless love affairs? Is it a cautionary tale about the dangers of giving your heart too quickly because of physical beauty? Or perhaps we could look at La Belle Dame sans Merci as an allegory, that she stands for something that may seem inviting at first, but can consume and take over your life. Drugs, perhaps. Or an obsession.

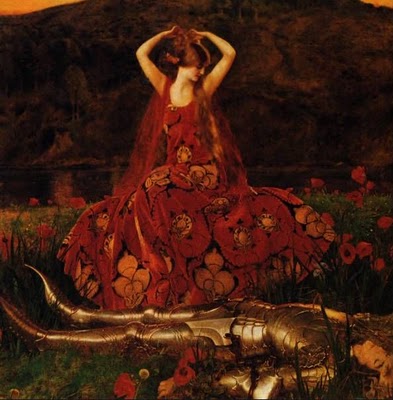

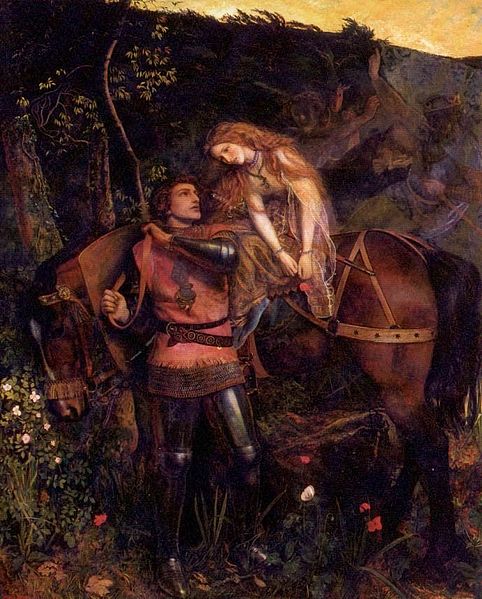

Above left is La Belle dame sans Merci by John William Waterhouse. On the right is a stunning recreation featuring Grace Nuth. Note the heart on the sleeve and the hair with which she ensnares her knight. Photographer: Richard Wood. Knight: Patrick Neill. Grace appears in many images that embrace the Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic and I encourage you to look at her work on her facebook page, Sidhe Etain. If you are interested in incorporating mythic themes into your home life, you should check out her blog Domythic Bliss. Domythic Bliss is currently celebrating the second annual Mythic March.

Above left is La Belle dame sans Merci by John William Waterhouse. On the right is a stunning recreation featuring Grace Nuth. Note the heart on the sleeve and the hair with which she ensnares her knight. Photographer: Richard Wood. Knight: Patrick Neill. Grace appears in many images that embrace the Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic and I encourage you to look at her work on her facebook page, Sidhe Etain. If you are interested in incorporating mythic themes into your home life, you should check out her blog Domythic Bliss. Domythic Bliss is currently celebrating the second annual Mythic March.

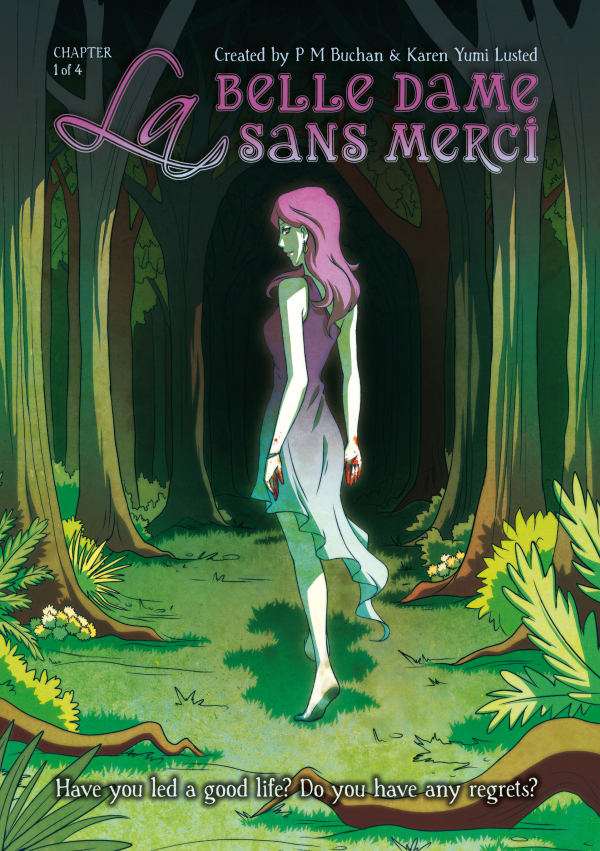

I’ve recently learned about a new graphic novel based on La Belle Dame sans Merci:

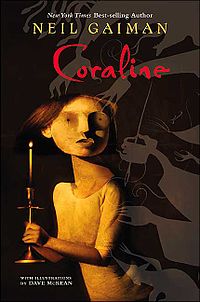

I’m intrigued by online speculation that the ‘beldame’ in Coraline may be loosely based on La Belle Dame sans Merci. I’ve enjoyed both the book and the movie and can see definite parallels between Gaiman’s “other mother” and the beautiful lady without mercy. Both would pull you into another world, taking over your very life and soul if you let them. And both the knight and Coraline encounter previous victims: the knight through a vision while he slumbers, Coraline meets their ghosts while trapped in a closet. The “other mother” cast them aside once bored with them, much like the beautiful lady of the meads did to the knight. Lucky for our knight that he did not end up with buttons for eyes.

Also see: Kirsty Stonell Walker’s La Belle Dame sans Merci post.

La Belle Dame sans Merci

O what can ail thee, knight-at-arms,

Alone and palely loitering?

The sedge has withered from the lake,

And no birds sing.

O what can ail thee, knight-at-arms,

So haggard and so woe-begone?

The squirrel’s granary is full,

And the harvest’s done.

I see a lily on thy brow,

With anguish moist and fever-dew,

And on thy cheeks a fading rose

Fast withereth too.

I met a lady in the meads,

Full beautiful—a faery’s child,

Her hair was long, her foot was light,

And her eyes were wild.

I made a garland for her head,

And bracelets too, and fragrant zone;

She looked at me as she did love,

And made sweet moan

I set her on my pacing steed,

And nothing else saw all day long,

For sidelong would she bend, and sing

A faery’s song.

She found me roots of relish sweet,

And honey wild, and manna-dew,

And sure in language strange she said—

‘I love thee true’.

She took me to her Elfin grot,

And there she wept and sighed full sore,

And there I shut her wild wild eyes

With kisses four.

They cried—‘La Belle Dame sans Merci

Hath thee in thrall!’

I saw their starved lips in the gloam,

With horrid warning gapèd wide,

And I awoke and found me here,

On the cold hill’s side.

And this is why I sojourn here,

Alone and palely loitering,

Though the sedge is withered from the lake,

And no birds sing.

All mythology is of the devil. No different than Disney

Care to explain your point of view, Kathy? Mythology has given us a vast literary landscape. I’m not sure why you see that as a negative thing.

The knight has consumption. The lady of the lake is consumption. She rues that. The poor fellow is dying.