When the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood formed, they met with resistance and negativity from throughout the art world. Charles Dickens was an especially harsh critic of their work and wrote a scathing review in his magazine Household Words, where he was particularly vicious towards the work of John Everett Millais.

Art critic John Ruskin was intrigued by the PRB and their principles reflected his own. He quickly published a rebuttal towards the brutal commentary levied towards them, saying that the brotherhood “may, as they gain experience, lay in our land the foundations of a school of art nobler than has been seen for three hundred years”.

The Pre-Raphaelites, especially Millais, were grateful for Ruskin’s support and he became both a mentor and friend to them.

Ruskin’s young wife, Euphemia “Effie” Gray Ruskin, was a spirited and charismatic woman with intelligence and wit. But she was also trapped in an unhappy, loveless marriage.

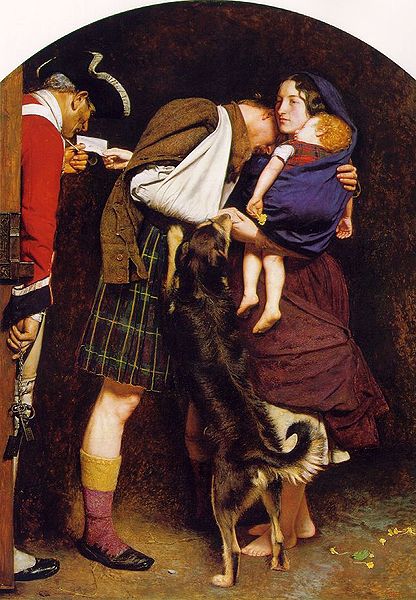

Millais and Ruskin’s friendship blossomed – together Effie and her husband commissioned Millais’ painting The Order of Release, and Effie gladly posed for it.

Ruskin was a cold husband and his parents, who coddled him, were harsh and judgmental toward Effie.

When Millais and his brother traveled with the Ruskins to Scotland, he softened towards Effie as he began to realize that her marriage was not all that it seemed.

Effie’s painful secret was that in five years of marriage, her virginity was still intact.

Ruskin was bitter when Effie wanted to vacate the marriage, and she had to submit to the humiliation of a medical examination to prove that their marriage had never been consummated.

Their subsequent annulment was the scandal of the season and a great source of embarrassment for not only Ruskin and Effie, but their extended families.

In 1855, Effie and Millais married.

Despite the fact that she confided to her diary that Millais wept uncontrollably while they exchanged their vows, he seems to have loved married life. He wrote to William Holman Hunt, “I can not enumerate the advantages now – Man was not intended to live alone.”

In later years she blamed her nervousness and insomnia on her years spent with Ruskin, although the eight children she and Millais had in quick succession must have also exacted a toll on her.

Effie was a loving wife who successfully put the past behind her. She would have been more successful if the memories of society had not been so acute – due to her annulment, Queen Victoria refused to allow her to be presented at court, although in 1896 she did grant Effie a private audience as Millais lay dying of throat cancer. Effie died the following year.

Effie’s marriages are still a topic of interest. The fact that her story has been told onscreen recently in both Emma Thompson’s film Effie Gray (2014) and the BBC program Desperate Romantics (2009) shows that even in our modern era where scandals usually contain more scurrilous notes, Effie’s marriage is still able to captivate us as much as it did her contemporary Victorians.