Inspired by artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s passion for wombats, every Friday is Wombat Friday at Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood. “The Wombat is a Joy, a Triumph, a Delight, a Madness!” – Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Thaddeus Fern Diogenes Wombat is a sleepy bloke today, but knowing his love for history and drama I’ve chosen to wake him up with a strong and beautiful ruler that has fascinated us for centuries. There are many representations of Cleopatra, but I’d like to introduce T-Dub specifically to Victorian depictions of her.

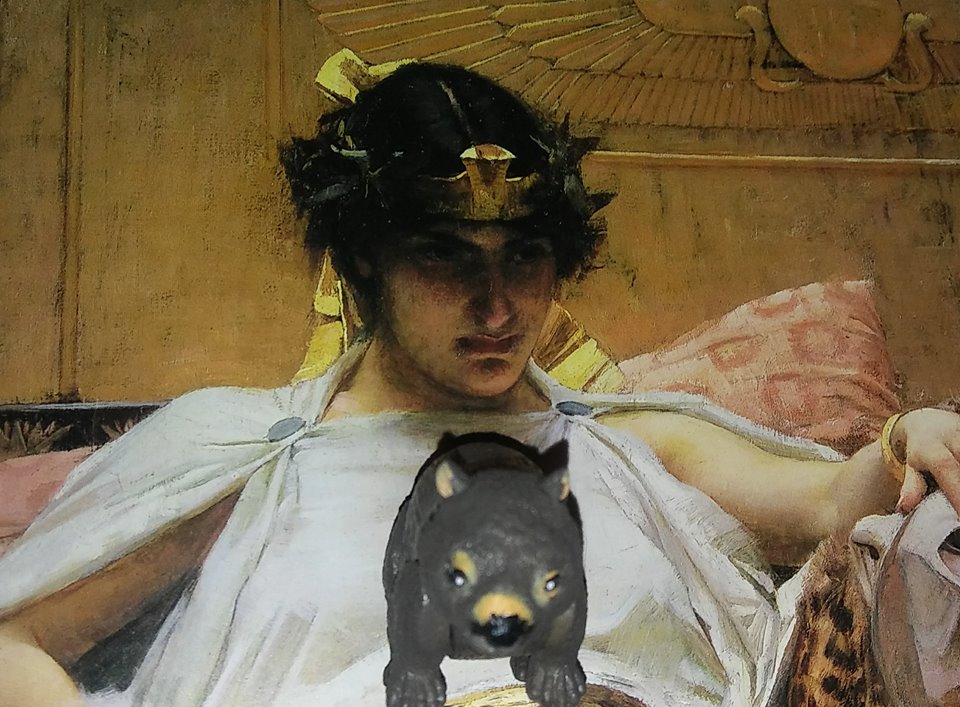

Although not technically a Pre-Raphaelite, it is obvious that the work of John William Waterhouse was heavily influenced by the Pre-Raphaelite style. His Cleopatra is reminiscent of Rossetti’s half-length portraits, complete with the unwavering gaze of a stunner. He portrays her seated on her throne in a position of power rather than choosing to illustrate the scene of her suicide, as so many artists have done.

Waterhouse displayed Cleopatra along with a quote from Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra: “Where’s my serpent of Old Nile? For so he calls me.” (Act I, Scene V)

In 1866, Frederick Sandys illustrated Algernon Charles Swinburne’s poetic vision of Cleopatra.

She treads on gods and god-like things,

On fate and fear and life and death,

On hate that cleaves and love that clings,

All that is brought forth of man’s breath

And perisheth with what it brings. (Cleopatra by Algernon Charles Swinburne, full poem here.)

The Victorians loved Shakespeare, so their perception of Cleopatra must have been shaped by Antony and Cleopatra. The play revolves around Cleopatra, who appears as a femme fatale. Such a woman was no doubt dangerous and, as such, was in direct contrast with what the proper Victorian woman should be. She could be admired from afar by an audience, but the thought of such a woman who would control her own destiny and manipulate others was not to be encouraged or tolerated within their own households. Cleopatra, a sensual and decadent ruler, provided an antithesis for the grave and wholesome influence of Queen Victoria.

Both Waterhouse’s painting and Sandys’ engraving show Cleopatra in gauzy free-flowing gowns that are not restrained by corsets. In Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s works, she is decadently adorned in leopard skin. The actresses below (Sarah Bernhardt and Lily Langtry) portrayed the Egyptian queen a bit later than the Pre-Raphaelite heyday. Their costumes are still a bit risque’ and they certainly look exotic. Yet they still cling (barely) to Victorian ideals of respectability.

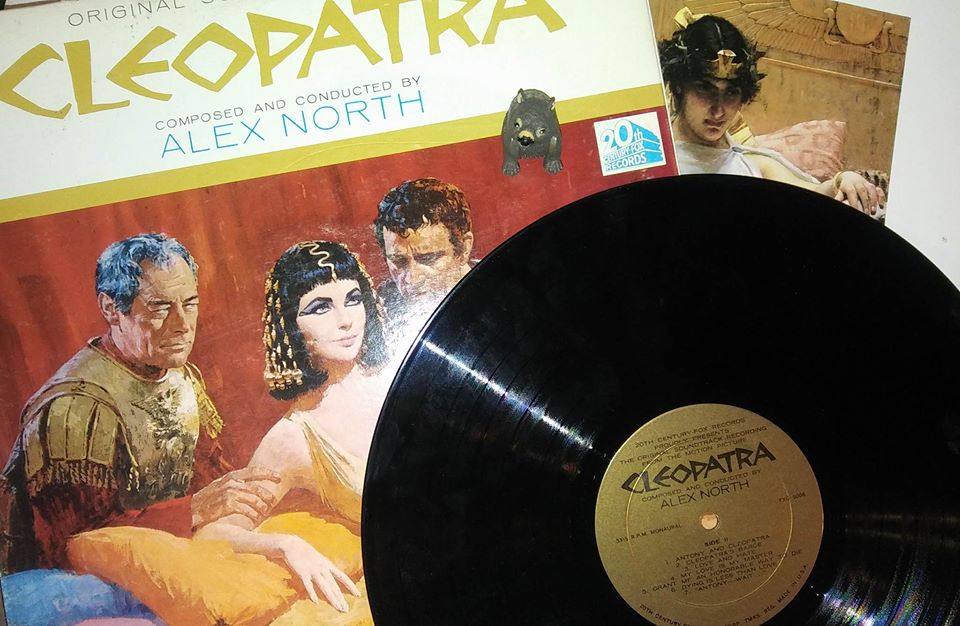

Cleopatra still fascinates us even though her legend has grown so much in over 2000 years that much of what captivates us is due to dramatic license. For many of us, Cleopatra is Vivien Leigh or Elizabeth Taylor. Both women gave commanding performances which may bear little resemblance to the life of Cleopatra herself. That should not deter us, however. It was productions such as these that encouraged my own love of history as a child and hopefully these tales still intrigue us enough that we still seek, read, and pursue.

The 1963 film Cleopatra starring Elizabeth Taylor, Richard Burton, Rex Harrison, Roddy McDowall, and Martin Landau is one of my all-time favorites and Landau’s recent passing may have been what brought Cleopatra to my mind this week. The film score, which I have on vinyl, is bold and sumptuous. I’ve told T-Dub that I’ll play it for him tonight is only he gets some actual work done today.