The Somnambulist by Sir John Everett Millais is a captivating image and many speculate that it is inspired by the Wilkie Collins novel The Woman in White. Millais was a close friend to both Wilkie Collins and his brother, artist Charles Collins. The Life and Letters of Sir John Everett Millais, written by the artist’s son, mentions the curious incident that Collins later recreated in his novel.

“Of Wilkie Collins there is little to be said in connection with the subject of the present work, though both he and his brother Charles were for many years amongst Millais’ most intimate friends, and no one more admired his brilliant talent as a novelist. Since his famous novel, The Woman in White, appeared, many have been the tales set on foot to account for its origin, but for the most part quite inaccurate. The real facts, so far as I am at liberty to disclose them, were these: —

One night in the fifties Millais was returning home to Gower Street from one of the many parties held under Mrs. Collins’ hospitable roof in Hanover Terrace, and, in accordance with the usual practice of the two brothers, Wilkie and Charles, they accompanied him on his homeward walk through the dimly-lit, and in those days semi-rural, roads and lanes of North London.

It was a beautiful moonlight night in the summertime, and as the three friends walked along chatting gaily together, they were suddenly arrested by a piercing scream coming from the garden of a villa close at hand. It was evidently the cry of a woman in distress; and while pausing to consider what they should do, the iron gate leading to the garden was dashed open, and from it came the figure of a young and very beautiful woman dressed in flowing white robes that shone in the moonlight. She seemed to float rather than to run in their direction, and on coming up to the three young men, she paused for a moment in an attitude of supplication and terror. Then, seeming to recollect herself, she suddenly moved on and vanished in the shadows cast upon the road.

“What a lovely woman!” was all Millais could say. “I must see who she is and what’s the matter,” said Wilkie Collins, as, without another word, he dashed off after her. His two companions waited in vain for his return, and next day, when they met again, he seemed indisposed to talk of his adventure. They gathered from him, however, that he had come up with the lovely fugitive and had heard from her own lips the history of her life and the cause of her sudden flight. She was a young lady of good birth and position, who had accidentally fallen into the hands of a man living in a villa in Regent’s Park. There for many months he kept her prisoner under threats and mesmeric influence of so alarming a character that she dared not attempt to escape, until, in sheer desperation, she fled from the brute, who, with a poker in his hand, threatened to dash her brains out. Her subsequent history, interesting as it is, is not for these pages.”

In The Woman in White, artist Walter Hartright encounters a beautiful woman dressed all in white while walking in the moonlight. Troubled and needing help, she speaks with him for a few moments and her desperation touches him: “The loneliness and helplessness of the woman touched me. The natural impulse to assist her and to spare her, got the better of the judgment, the caution, the worldly tact, which an older, wiser and colder man might have summoned to help him on this strange emergency.”

The next day, Hartright meets his new pupils and is shocked that one of them, Laura Fairlie, is practically a doppelganger to the woman in white. He tells Laura and her sister Marian of the strange incident and soon the threesome are pulled into mysterious and cruel circumstances that will change the rest of their lives.

Collins and his fictional creation William Hartright were both stunned and captivated to meet a woman in distress and the strangeness of her costume added an almost supernatural flair to the incident. The entirely white ensemble must have been quite ghostly in appearance due to the moonlight and Caroline Graves (the real life woman in white) really was in trouble. Collins went on to have a complicated relationship with her that would last until his death.

Collins used the white ensemble as a literary device, playing upon the symbolism associated with the color white: goodness, innocence, purity.

The first Pre-Raphaelite painting to show a woman dressed in stark white was Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Ecce Ancilla Domini. You can not get more virginal than that.

Rossetti shows the Virgin Mary as she is visited by the angel Gabriel. Not only is she dressed entirely in white, but she is also surrounded by her white bedclothes. This raised the ire of critics who felt it was inappropriate to see Mary in bed.

Burne-Jones also used the contrast of white and black in Fair Rosamund and Queen Eleanor.

Fair Rosamund, mistress of King Henry II, is depicted in light colors that represent innocence or virginity. In contrast, Queen Eleanor wears an angry black. Despite being the wronged wife, it is the fair Rosamund that we pity. The fear is visible on her face. Rosamund is trying to flee, but it is obvious that she is going nowhere. The wronged Queen Eleanor will have her revenge.

But does white always reflect purity and innocence?

In both Lady Lilith and Fazio’s Mistress, Rossetti painted women all in white. Yet he wrote of Lilith as being a witch in his accompanying poem and the very title of Fazio’s Mistress tells us exactly who and what she is.

Although clothed in white, her gown slips provocatively off her shoulder while she combs her hair in her bedchamber. A direct contrast with how Mary is presented in her bedchamber in Ecce Ancilla Domini. White may represent purity, but in both the Lilith and the Fazio painting, their flowing hair and the exposed shoulders due to the looseness of their gowns may symbolize eroticism.

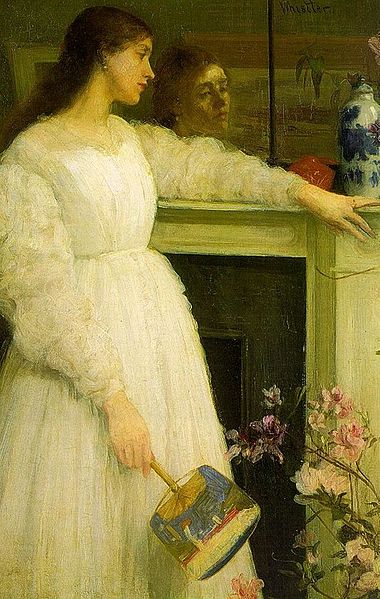

James McNeill Whistler used white as an allegory of innocence in Symphony in White, No. 1 and we can not deny the obvious similarity it has to Millais’ The Somnambulist.

“..a woman in a beautiful white cambric dress, standing against a window which filters the light through a transparent white muslin curtain – but the figure receives a strong light from the right and therefore the picture, barring the red hair, is one gorgeous mass of brilliant white.” –Whister describes Symphony in White in a letter to George DuMaurier.

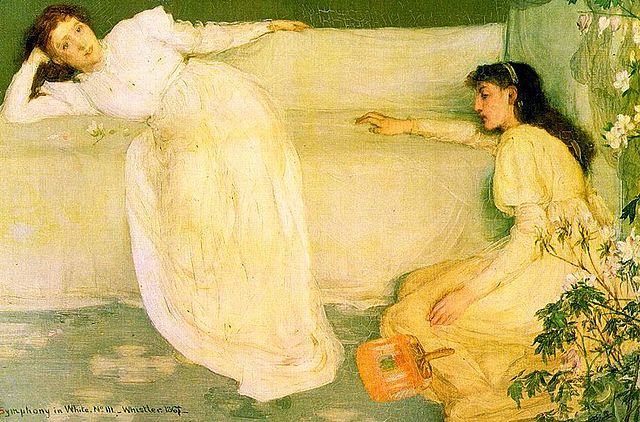

Whistler revisits his theme of white in Symphony in White, No. 2 (also known as The Little White Girl) and Symphony in White, No. 3.

In all three of his ‘Symphony in White’ paintings, Whistler used Joanna Hiffernan as a model. He may have portrayed her in virginal white, but she was his mistress. She wears a ring in Symphony No. 2, but the two were never married.

I’d like to spend the rest of this week exploring Wilkie Collins, The Woman in White, and the possible influence of the Pre-Raphaelites on his work. It’s been a few years since my last Woman in White reading, so expect more posts on it.