Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s sonnet Life-in-Love fascinates me, especially when read with knowledge of two great loves in his life: Elizabeth Siddal and Jane Morris. The first two lines suggest that his deceased lover’s life has somehow migrated into the body of his new love: Not in thy body is thy life at all/But in this lady’s lips and hands and eyes. The last line, Lies all that golden hair undimm’d in death, evokes thoughts of Elizabeth Siddal as she reportedly appeared at her exhumation, with her famous red-gold hair filling the coffin. Remember that the exhumation was a private affair and not public knowledge. When Rossetti wrote that line it may have never occurred to him that one day readers would hear accounts of Lizzie’s disinterment or the myth of her rebellious tresses. Yet as DGR himself put it in a letter to his brother, the truth must ooze out in time.

Not in thy body is thy life at all

But in this lady’s lips and hands and eyes;

Through these she yields thee life that vivifies

What else were sorrow’s servant and death’s thrall.

Look on thyself without her, and recall

The waste remembrance and forlorn surmise

That liv’d but in a dead-drawn breath of sighs

O’er vanish’d hours and hours eventual.

Even so much life hath the poor tress of hair

Which, stor’d apart, is all love hath to show

For heart-beats and for fire-heats long ago;

Even so much life endures unknown, even where,

‘Mid change the changeless night environeth,

Lies all that golden hair undimm’d in death.

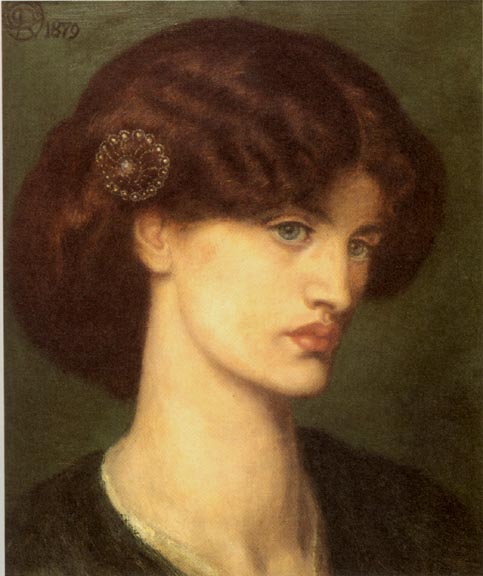

When we look back on Rossetti’s work, we can find several instances where images of Lizzie and Jane seem to blur. It is important to note that this didn’t happen abruptly. He did not come home from Lizzie’s funeral and hurtle headlong into obsessive images of Jane. This was something that evolved over several years and contrary to the narrative of Rossetti as a selfish libertine, manifested itself during a painful time when he struggled with his mental health.

Elizabeth Siddal was often in ill-health and many of Rossetti’s drawings of her in the 1850s are images of her resting. In the 1870s he would draw similar sketches of Jane when she also endured periods of illness.

Early in his relationship with Elizabeth Siddal, Rossetti seemed to idealize her and view her as his Beatrice, the love immortalized by Dante Alighieri in La Vita Nuova. Later works would feature Jane Morris as Beatrice.

With his wife no longer a living muse she becomes an even more Beatrice-like figure, unreachable in the after-life. In his posthumous tribute to her, Beata Beatrix, he painted her as Beatrice on the brink of death.

However, in later versions of the work the features become less like Lizzie’s and more like his depictions of Jane.

Whether intentional or not, at times his work appears to be a Lizzie-Jane hybrid. We can not ignore that this was during a period of mental anguish for him. Rossetti’s physical complaints –his hydrocele, growing worries about his eyesight– led to hypochondria and paranoia. He began to believe that he was going blind just as his father had towards the end of his life. Perhaps painting images with features of Lizzie and Jane were a manifestation of his mental health. Was it cathartic? His way of seeking comfort? Or is it merely coincidence?

Or perhaps they are images of neither just Lizzie and Jane, but a composite that creates Rossetti’s ideal woman. A woman that symbolizes something much deeper than mere physicality. Perhaps she is the divine feminine or as in Rossetti’s Hand and Soul, a reflection of the soul. Whatever Rossetti intended to create, in my opinion he gave us images that are beautiful and powerful, a blending of the sensual and the heavenly.