Possession is an intricate novel written in 1990 by A.S. Byatt. A combination of mystery, myth, and romance, it is a book that delves into the lives of two 19th century poets and the pair of 20th century-era academics that attempt to piece together the poets’ lives. When I assess the books I have loved throughout my life, Possession is one that stands apart, gleaming in my memory in magical, jewel-like tones.

When I first read it, I was a seventeen-year-old girl with an intense literary craving. It was Sir Edward Burne-Jones’ painting The Beguiling of Merlin on the cover that drew me to the book. And after I dove in, I emerged with new eyes.

Byatt’s work has influenced me in more ways than I can possibly share. Now, at age forty-two, I have happily encountered many friends in several areas of my life who have had similar experiences with Possession. It’s a rich, complex book with many layers.

It is a friend to me, and I to it.

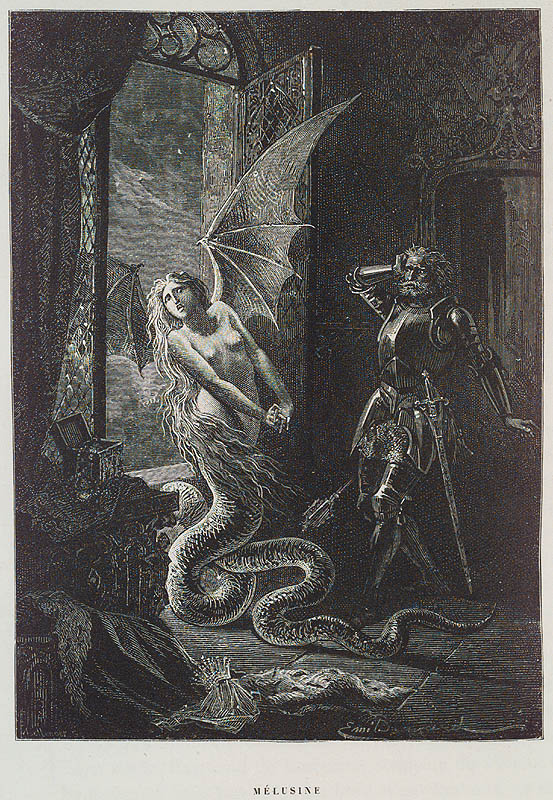

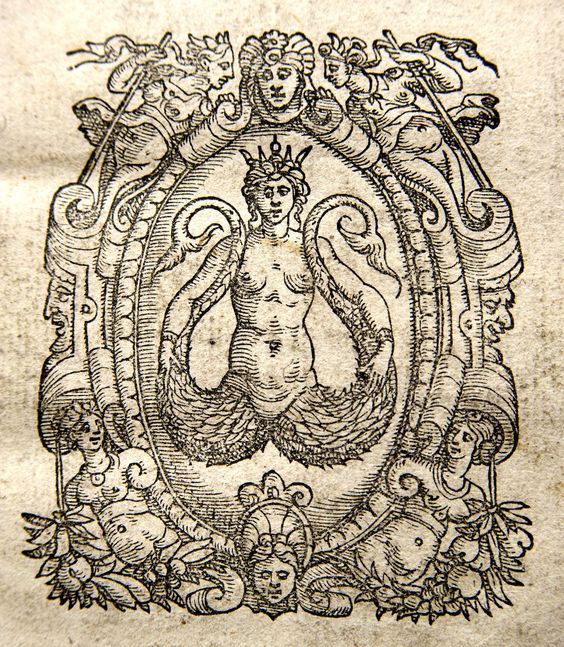

The legend of Melusine is woven into the narrative of Possession, and the symbolism of that story is something I have been unraveling a lot lately. She has been described as a serpent goddess, siren, or water fairy who married a mortal. He was unaware of her mystical nature and upon marriage, she asked him to promise to never enter her chamber on a Saturday, the day she would transform. He agreed, allowing her to keep the serpentine side of herself a secret.

Eventually, though, he broke his promise.

Possession was my glistening introduction to Melusine, and I fell in love with her immediately. Funny, but most of us see her almost daily. There she is, hiding in plain sight, right there in the Starbucks logo.

The logo has been updated several times over the years. Melusine’s two tails may be hidden now, but you can’t fool us; it’s still her. I think the fact that her tails are obscured in the current iteration is quite fitting, actually. It jibes with her legend since her primal, monstrous side wasn’t meant to be seen by her husband.

The story of Melusine has been popular in France and other areas of Europe for centuries. Through Possession, Byatt helped share the tale to a wider, modern audience.

It is a book of many metaphors, and Melusine is a captivating and important symbol. Reading it more than once throughout my adulthood gave me what I thought to be a solid grasp on the meaning of the Melusine legend. But my recent divorce brought fresh insights and interpretations to me.

Like the serpentine maiden transforming in her bath, the demise of a relationship brings out what can be perceived as ugly. Regrets, past choices and unconsious patterns all come bubbling to the surface, and it’s very often not pretty.

But by staying the course, a point can be reached where peace is made with the happiness and pain. A couple’s shared history becomes a figurative Melusine of sorts – lovely happy moments juxtaposed with painful ones. When we have enough distance to face these experiences objectively, we learn about each other as well as ourselves. Hopefully, we take what we learn and use it to create a healthier future.

In Possession, the character Christabel LaMotte is obsessed with Melusine. In Chapter Three, two scholars discuss her in detail:

“Who was she?”

“Christabel La Motte. Daughter of Isadore, the mythographer. Last Things. Tales Told in November. An epic called The Fairy Melusina. Very bizzare, Do you know Melusina? She was a fairy who married a mortal to gain a soul, and made a pact that he would never spy on her on Saturdays, and for years he never did, and they had six sons, all with strange defects–odd ears, giant tusks, a catshead growing out of one cheek, three eyes, that sort of thing, One was called Geoffroy a la Grande Dent and one was called Horrible. She built castles, real onesthat still exist in Poitou. And in the end, of course, he looked through the keyhole…”

In the 1990s, Roland Michell and Maude Bailey are the scholars on the trail of a possible 19th century Ash-LaMotte connection.

Maude Bailey discusses Christabel, saying “After Melusine she appears to have written no more poetry, and retreated further and further into voluntary silence”. Later, we see Randolph Henry Ash’s rhetorical observation, “Could the Lady of Shalott have written Melusina in her barred and moated Tower?” Melusine is a story of secrets and transformation, but like the Lady of Shalott, it also has elements of isolation and loneliness.

Christabel describes herself as the Lady of Shalott in a letter to Ash:

“I have chosen a way — dear Friend — I must hold to it. Think of me if you will as the Lady of Shalott — with a narrower wisdom — who chooses not the Gulp of outside air and the chilly river-journey deathwards — but who chooses to watch diligently the bright colors of her Web — to ply an industrious shuttle — to make — something — to close the shutters and the peephole to —

You will say, you are no threat to that. You will argue — rationally. There are things we have not said to each other beyond the — One — you so starkly — Defined.

I know my Intrinsic Self. The Threat is there.

Be patient. Be generous. Forgive.”

She is gently letting him know of her need for isolation and privacy in order to write. She is Melusine, knowing she needs her bath chamber as a private space to be who she is.

In the myth, Melusine has a dual nature: she is lightness and dark – both beautiful and repulsive.

Folklore is filled with the unlikely marriages of swan maidens, frog princes, beauties and beasts. Melusina follows that fairy-tale pattern of marrying someone other.

Perhaps we are supposed to be as fearful of her as her husband was when he discovered her secret, yet my instinct now is to celebrate her. To me, she represents the parts of ourselves that we are ashamed of and hide away, sometimes unknowingly, until we learn to embrace and take responsibility for our own growth and empowerment.

If I look at her as a symbolic role model for women, I have to ask myself how we can apply her story to our modern lives. If we are lucky, we choose partners in life who trust and encourage our empowerment no matter what they see through that metaphorical keyhole.

Spying on her as she bathes, her husband is horrified when he sees her monstrous incarnation. Yet, is she truly monstrous? Where most people would recoil at her serpent-like nature, maybe we should look at her, face her, and deconstruct who she is.

Serpents shed their skin, constantly renewing themselves. This is a woman who remains herself, yet embraces growth and rejuvenation. That deserves respect.

Yet she is not only a serpent-goddess. She is a woman with fears and needs and insecurities. She is a wife and mother who wisely knows that she needs time to herself. And in that private time, she is free to be herself.

So, which side of Melusina is the real one? Both, of course.

How does she balance the different sides of herself? By understanding and voicing what she needs. While her husband ultimately did not respect her boundaries or the agreement they made, an aspect of the story that should not be wasted on modern women is that she voiced her needs.

She needed a day to herself. She needed a day to be herself. She needed a day to rejuvenate herself.

We struggle and muddle through our lives as best we can, but instead of hiding our flaws away in the belief that they are ugly and monstrous, let’s demand time for reflection and renewal.

We should not be objectified and defined solely by our beauty or our flaws. What matters is the work we put in to understanding ourselves.

Like a serpent-goddess, we have to outgrow the skin of that which doesn’t serve us.

Saying those things feels real and true to me. But by the same token, my observations feel shallow in comparison to all Byatt achieved in Possession.

I can not reduce Melusina into a mere parable of the benefits of taking time for self-care. She represents the ache of loss and the tragedy of hiding one’s self away, all wrapped up in a swirling, irridescent tale. She is a myth that can not be deconstructed in one sitting.

Melusine’s duality fits in to Possession seamlessly; it is a work that is itself of dual nature. Twin time periods and double meanings are the meat and potatoes of this book. So my interest in Melusine may not be about Melusine herself, but Melusine within the context of Byatt’s story.

I think Byatt does an excellent job equating more than one character with Melusine. Her Victorian poet, Christabel LaMotte, is a reclusive Melusine, whose pen is the instrument of her power. Her poetry is included in the book. Feast yourself on this delicious nugget:

Men may be martyred

Any where

In desert, cathedral

Or Public Square.

In no Rush of Action

This is our doom

To Drag a Long Life out

In a Dark Room

In the 1990s narrative of the book, the Maud Bailey character embodies Melusine. Here is where Byatt wields her power masterfully. Both Christabel and Maud are real-world representations of the fairy-serpent-goddess, but in vastly different ways.

Maud’s modern academic life differs from LaMotte’s reclusive existence in a wooded cottage. Maud is isolated not in seclusion, but while being surrounded by people. She intimidates men and is described as one who “thicks men’s blood with cold,” yet she is also shunned by her fellow feminist colleagues because they assume her naturally white-blonde hair is a dyed attempt at superficial beauty and conformity.

Maud has the otherness of a Melusine along with the drive and desire to analyze the threads of the fairy-serpent’s story as told by LaMotte. It is through piecing together LaMotte’s history that Maud discovers truths about herself.

Byatt shows us there is more than one way to embody Melusine’s power and frailty. Femininity takes many forms – the trio of Melusine, Christabel, and Maud are superb examples.

For me, the core of Possession is the pursuit of truth and knowledge. I am now starting to realize that my perception of Melusine is about that same truth – understanding who and what I am, what I stand for, and what I choose to allow in my life.

I am not delving as deeply here into the book as you might have expected. If you have not yet read it, my hope is that you will take the plunge and share your thoughts with me about the profound metaphors that weave their way through Byatt’s writing.

Warning: what is woven throughout the book has a way of planting itself into your heart. It is a delightful labyrinth and, like Melusine, it’s not at all what it appears to be on the surface.

But then, neither are we.

Fascinating! Now I need to go and reread the novel. It’s been some years, and I never made the Melusine connection you so expertly delineate here, so it will be fascinating to reread it in that light.

It is so good to find someone else who has been “possessed” by Possession. This is an insightful discussion of Melusina, Christobel and Maud Bailey. Thanks for sharing. I suppose I must be a member of the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood with a lowercase b.