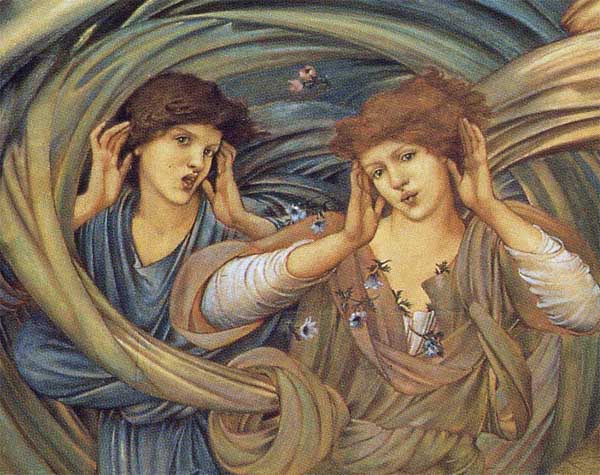

Sponsa de Libano is inspired by the Song of Solomon: ‘Awake O North wind; and come then south; blow upon my garden that the spices thereof may flow out.’ (Song of Solomon 4:16)

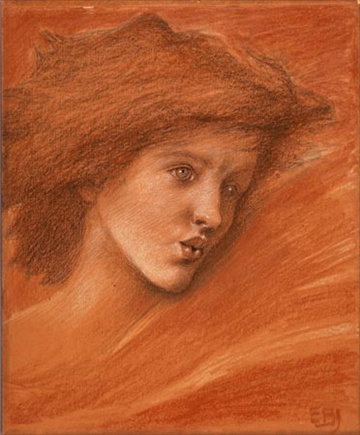

“I drew the South wind one day and the North wind the next. Such a queer little model I had, a little Houndsditch Jewess, self-possessed, mature and worldly, and only about twelve years old. When I said to her, ‘Think of nothing and feel silly and look wild and blow with your lips,’ she threw off Houndsditch in a moment, and thousands of years rolled off her and she might have been born in Lebanon, instead of the Cockney which she was. I will shew you the pictures.” –Sir Edward Burne-Jones in a letter to Lady Rayleigh, quoted from The Memorials of Sir Edward Burne-Jones, vol. II

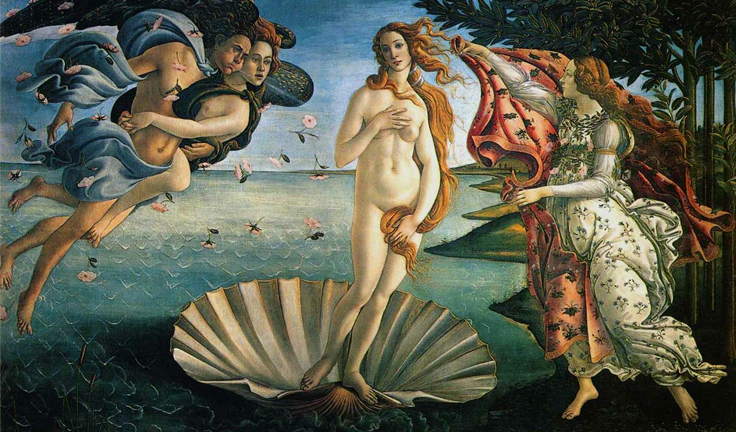

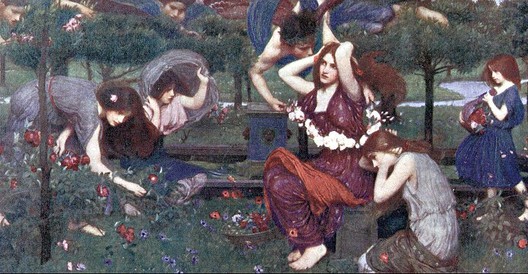

The North and South winds, seen in the detail below, remind me of Botticelli’s works The Birth of Venus and Primavera. This is not a surprise or a great discovery, it is well documented that Burne-Jones loved the works of Botticelli.

Author Fiona MacCarthy delves into his admiration for the Italian artist in The Last Pre-Raphaelite and points out that Burne-Jones was an early aficionado, prior to Ruskin’s lectures and Pater’s writings that helped make Botticelli both a household name and a symbol of the Aesthetic Movement.

Burne-Jones first viewed Botticelli’s work in 1859 during his first Italian sojourn. As MacCarthy points out, he clung to his passion for the Renaissance artist throughout his life.

He kept Botticelli with him, an ideal and a safeguard. In the bleaker years back home he kept on yearning to return to Botticelli like an old friend or a lover, with growing desperation: ‘I want to see Botticelli’s Calumny in the Uffizi dreadfully, and the Spring in the Belle Arte, –and the Dancing Choir that goes hand in hand up to heaven over the heads of four old men, in that same dear place.’–The Last Pre-Raphaelite, Fiona MacCarthy

Zephyrus, the god of the west wind, blows Venus toward dry land. Embracing him is Flora, goddess of flowers. Together they encourage the growth of new life.

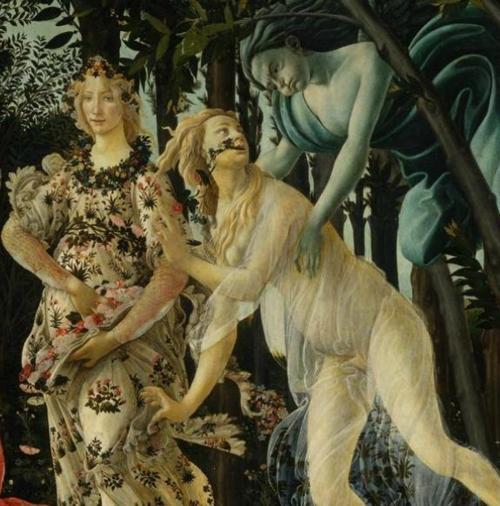

I find a section of Primavera similar to Sponsa de Libano as well, although I have to admit that this connection is a more of a stretch since both the composition and subject matter are different than The Birth of Venus and Sponsa de Libano. Instead of two figures blowing wind toward the main figure of the painting, Botticelli’s figures are facing each other as Chloris is abducted by Zephyrus.

Interestingly, they are the same characters as seen in The Birth of Venus. In the detail above, Flora is on the right. She is next to her previous incarnation, Chloris, being abducted by Zephyrus.

I enjoy Burne-Jones’ personification of the North and South winds. Waterhouse is another Victorian artist who created wind-themed images that I adore, mainly his works Flora and the Zephyrs and Boreas.

“ZEPHYROS (or Zephyrus) was the god of the west wind, one of the four directionalAnemoi (Wind-Gods). He was also the god of spring, husband of Khloris (Greenery), and father of Karpos (Fruit).”–via Theoi.com

Zephyrus kisses Flora’s arm as he wraps a garland of white roses around her. Although she is surrounded by beautiful nymphs, his focus on Flora is constant. This is a story of transfiguration: Flora is transformed into the goddess of flowers.

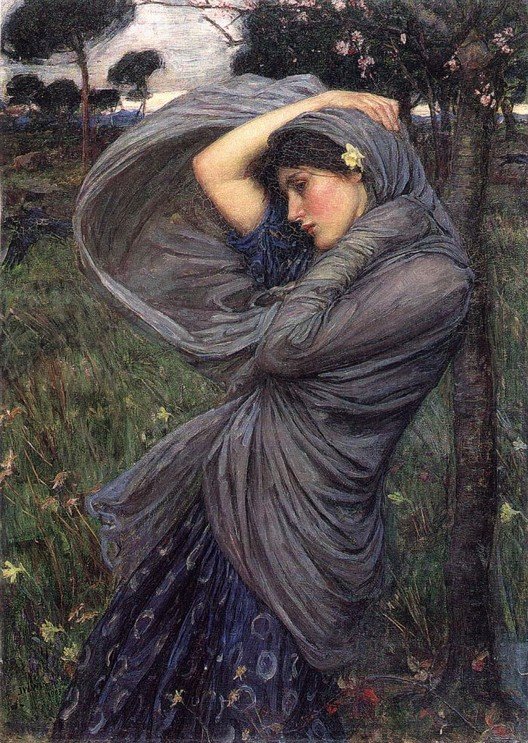

In a tale told by Ovid, Boreas was the North Wind and the brother of Zephyrus. Smitten with the maiden Oreithyia, who rejected him, he abducted her as she was picking flowers and married her.

Waterhouse depicted Flora in a posture that could be interpreted as open and receptive to Zephyrus. There’s a different attitude in Boreas: swathed in her drapery, Oreithyia has her arms lifted in a protective pose, attempting to shield herself from the wind. It almost seems to mimic the fetal position.

Waterhouse also visits wind as a subject in 1903’s Windflowers. Here her arms are less protective and more indicative of the personal chaos of being caught in the wind as she attempts to both hold her hair in place and keep control of her skirt and flowers.

Zephyrus The Awakener

Come, thou awakener of the spirit’s ocean,

Zephyr, whom to thy cloud or cave

No thought can trace! speed with thy gentle motion! –Percy Bysshe Shelley