Author Henry James had seen Rossetti’s paintings of Jane Morris during a visit to Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s studios. Upon seeing Jane in person, he had this to write:

“A figure cut out of a missal – out of one of Rossetti’s or Hunt’s pictures – to say this gives but a faint idea of her, because when such an image puts on flesh and blood, it is an apparition of fearful and wonderful intensity. It’s hard to say [whether] she’s a grand synthesis of all the pre-Raphaelite pictures ever made – or they a “keen analysis” of her – whether she’s an original or a copy. In either case she is a wonder. Imagine a tall lean woman in a long dress of some dead purple stuff, guiltless of hoops (or of anything else, I should say) with a mass of crisp black hair heaped into great wavy projections on each of her temples, a thin pale face, a pair of strange, sad, deep, dark Swinburnish eyes, with great thick black oblique brows, joined in the middle and tucking themselves under her hair, a mouth like “Oriana” in our illustrated Tennyson, a long neck, without any collar, and in lieu thereof some dozen strings of outlandish beads – in fine Complete. On the wall was a large nearly full-length portrait of her by Rossetti, so strange and unreal that if you hadn’t seen her, you’d pronounce it a distempered vision, but in fact an extremely good likeness.”

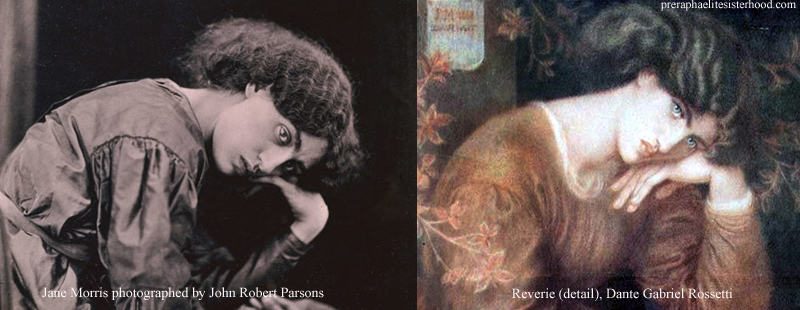

We might ask the same question presented by James: are Rossetti’s paintings of her a keen analysis? While it is often remarked upon that Rossetti has a tendency to stylize his portraits of women, Jane Morris on canvas is still recognizable as the real Jane Morris. Even though he adds those particular Rossettian touches of serpentine necks and cupid’s bow lips, Jane is still Jane. In the comparison below we can see that he has made her features more delicate, but the photograph of her shows that apart from this Rossetti stayed somewhat true to her features.

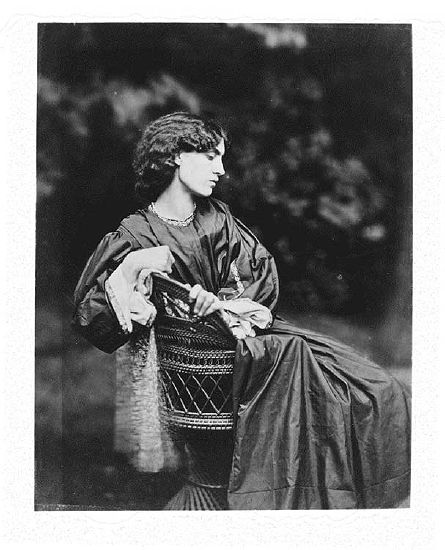

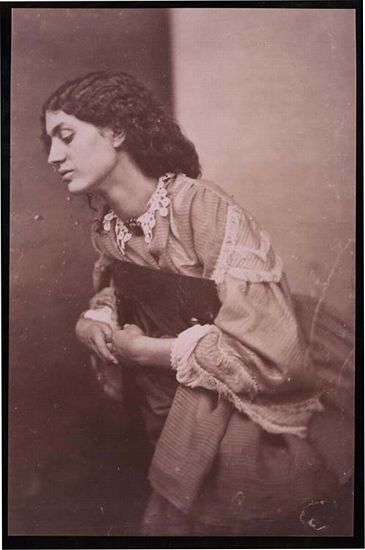

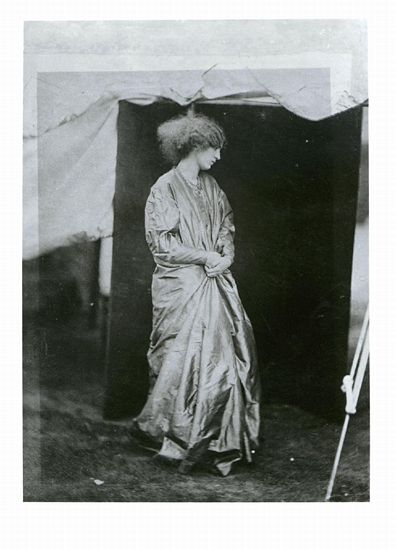

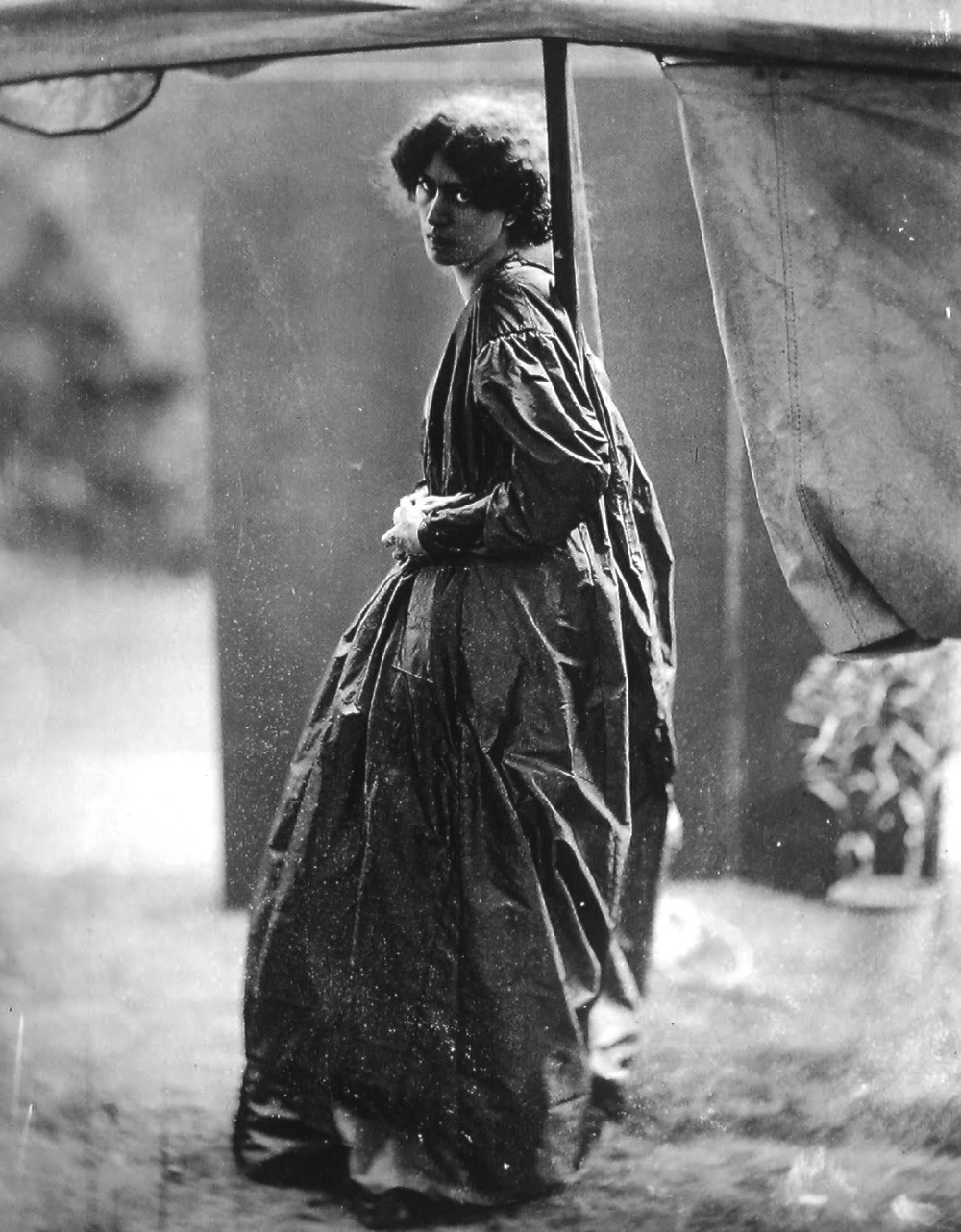

In 1865, Rossetti arranged for John Robert Parsons to photograph Jane in the garden of Tudor House. A marquee was erected and Jane is seen posing under it. Other photos were taken of her against a black background, reclining on a couch, and sitting in a chair. Many photographs were taken that day; I will only include a few here.

My favorite of the photographs is the one below. Her eyes appear unwavering, almost as if she has sized us up and found us wanting. In Rossetti’s works she often appears enigmatic and hard to read. Playwright George Bernard Shaw described her as “the silentest woman he had ever met” and this photograph seems to capture this mysterious aura that seemed to surround Jane. As in Rossetti’s painting Astarte Syriaca, I draw inspiration from the image of Jane.

In her biography of Rossetti, Jan Marsh draws a comparison between these photos and Felix Nadar’s images of actress Sarah Bernhardt.

Unlike The Divine Sarah, Jane was not a conventional beauty. Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s notions of beauty were decidedly different than the Victorian status quo. The great muses in his life had striking and unique features that did not fit with the societal norms of the time.

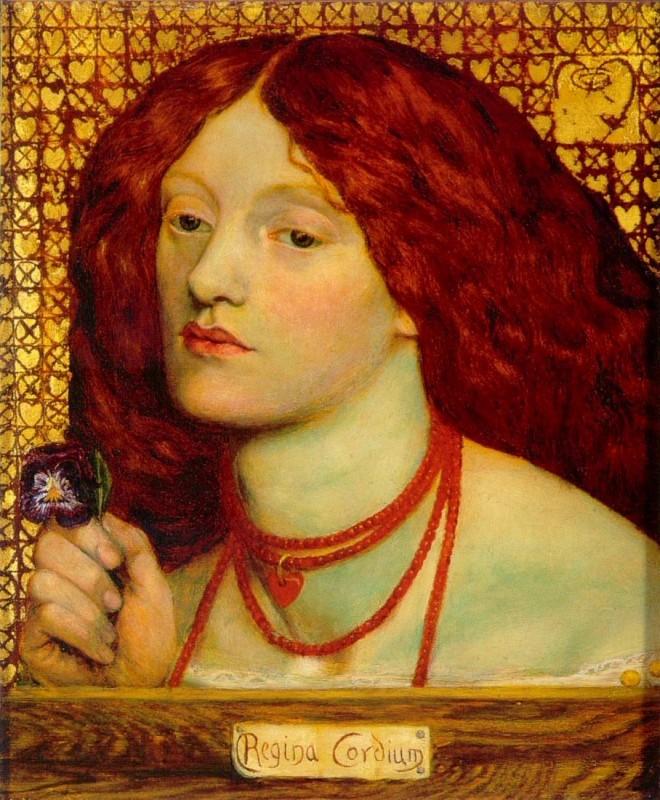

Years earlier, Rossetti painted and drew Elizabeth Siddal obsessively.

Siddal had been discovered by Walter Deverell while she worked in a millinery shop and although the story of her discovery has been embellished, she was not discovered because of her beauty. In The Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood, Dr. Jan Marsh points out that it was Siddal’s plainness that prompted Deverell to include her in his painting Twelfth Night. She then went on to pose for other Pre-Raphaelite artists, the most famous example being John Everett Millais’ painting of Ophelia.

After her relationship with Rossetti began, she sat for him exclusively while pursuing her own artistic career. Rossetti married her in 1860, although she died a mere two years later. Her influence on Pre-Raphaelite art was unmistakable and it is partly because of this (and her tragic death) that her legendary beauty was then described in hindsight.

Rossetti’s images of Elizabeth Siddal are beautiful and haunting.

Pre-Raphaelite images of women with gorgeous red hair helped to challenge the perception that red locks were both ugly and unlucky.

Rossetti’s works brought out the delicacy and beauty that he saw in Siddal’s features, but when it came to her own self-portrait she chose to present herself honestly and plainly.

It is the simple nature of Siddal’s portrayal of herself that inspired the title of Valerie Meachum’s play about the Pre-Raphaelite model and painter: Unvarnished.

I recently read an article about Jane Morris that described her as the ‘ideal Pre-Raphaelite beauty’, but it should be pointed out that there was no unified ideal among the Pre-Raphaelite circle.

Women of different shapes and sizes were inspirations and the strengths of each have merged into what we now recognize as the Pre-Raphaelite Stunner. While I have only used Jane Morris and Elizabeth Siddal as examples in this post, many women painted by the Pre-Raphaelites represented beauties that were unconventional for the time.

What does this mean for us? Rossetti saw something compelling and beautiful in the women he painted and he magnified those features in his works. Like Rossetti, perhaps we should not be dictated by societal views of what is beautiful.

Perceptions of beauty should be individual and unique. Let’s try to resist narrow definitions imposed upon us by society and media. Perhaps it’s not something we can change in society as a whole, but we can definitely change the way we think about ourselves and how we judge the physical appearance of others.

It starts with us changing our own inner voice. The idea of our own worth should not come whispered to us from outside sources, like the curse in The Lady of Shalott.

Many critics have raised concern that Pre-Raphaelite art is a creation of and for the male gaze, a valid critique that we must discuss and explore. However, it is also worth contemplating the unconventional aspects of the beauty presented in Pre-Raphaelite works and how we can interpret them in our own lives today.

“Taking joy in living is a woman’s best cosmetic.”–Rosalind Russell

Thanks for your wonderful blog! Do you know if there is any biography of Jane Morris translated in italian? If not, what’s the best english biography in your opinion?