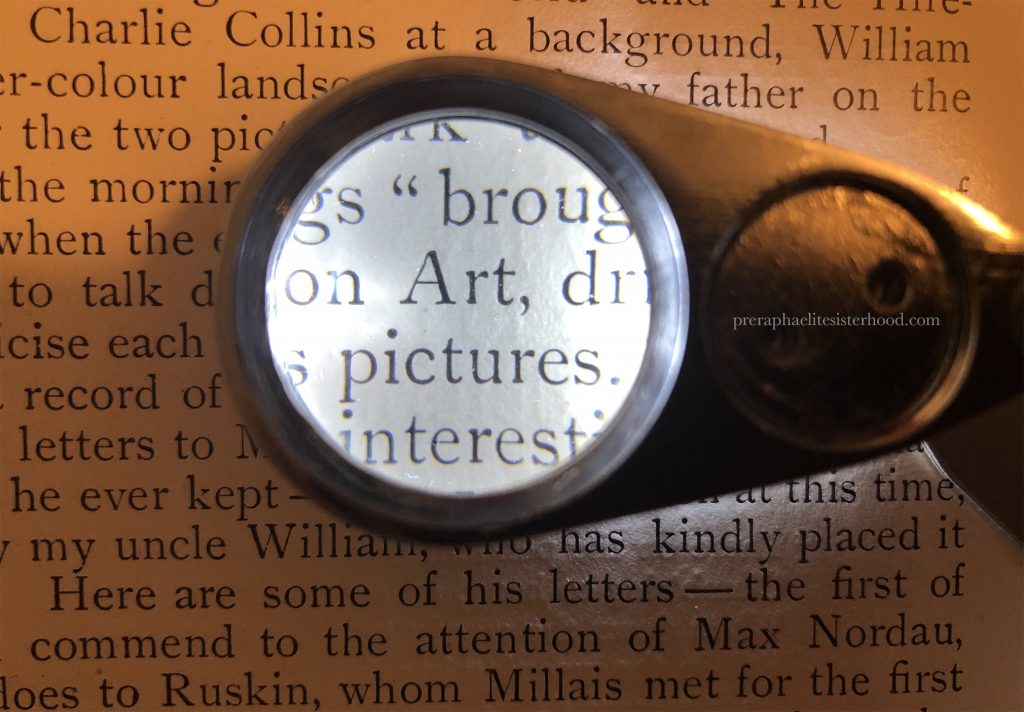

I have a loupe and I’m not afraid to use it.

Yes, a jeweler’s loupe is one of the weapons happily holstered in my artistic arsenal. I find it extremely useful and fun when exploring the art encased in quality prints and books.

Recently, I chose to wield my weapon on Mariana by Sir John Everett Millais.

My gracious, does Millais’ work stand the test of time! Let’s look through my loupe at what he did.

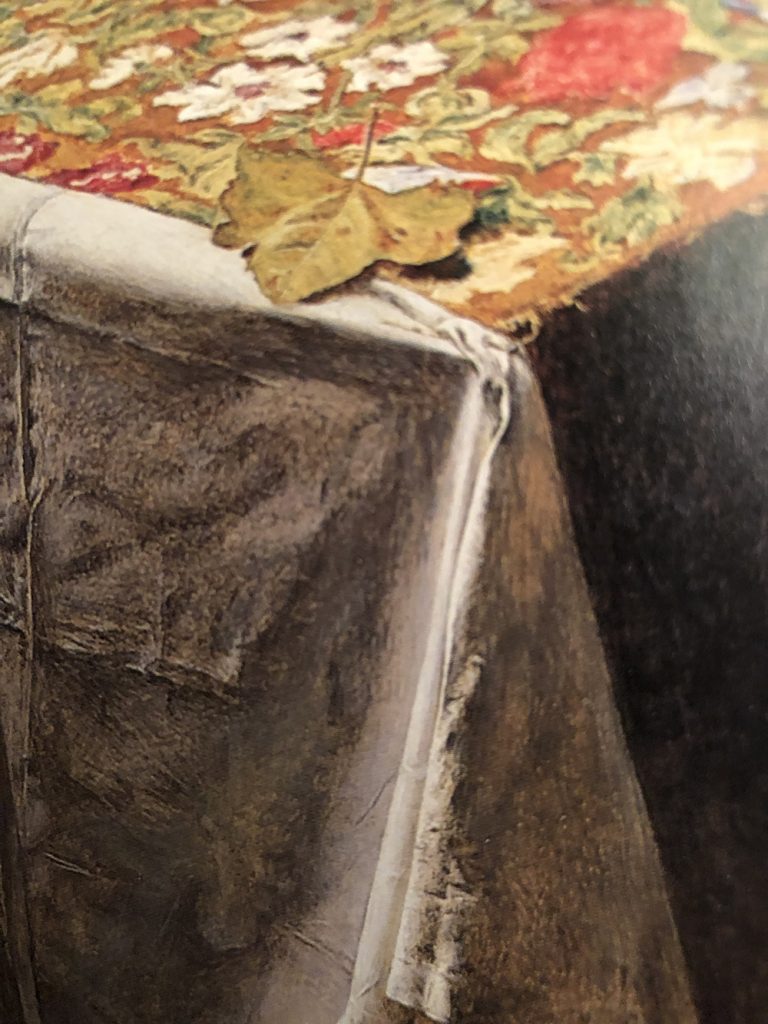

To begin, I am practically giddy about the precise folds in this cloth.

The Pre-Raphaelites were committed to creating realism in their works and one way Millais achieved this was by portraying the natural folds and cascades we see in this fabric.

Speaking of delightful textures, we must take a slight detour from Mariana to drink in the stunning, hyper-realistic creases of the gown worn in The Black Brunswicker.

Back to Mariana, Millais also captured the lush softness of her velvet gown, as well as the intricacy of the embroidery on the wall behind her.

As beautiful these details are, there are obvious limitations to the quality of reproduction of a painting within a book. Mariana’s dress is known for its electric blue hue and it is understandably difficult to capture that in a printed recreation.

Nevertheless, it remains stunning, recalling the wonder of a child delighting in The Wizard of Oz on a black-and-white TV, then being further entranced when later discovering its technicolor wonders.

Here’s the complete, vivid image from the Tate website for reference.

What a gift it is to bask in the enticing cobalt hue of her dress.

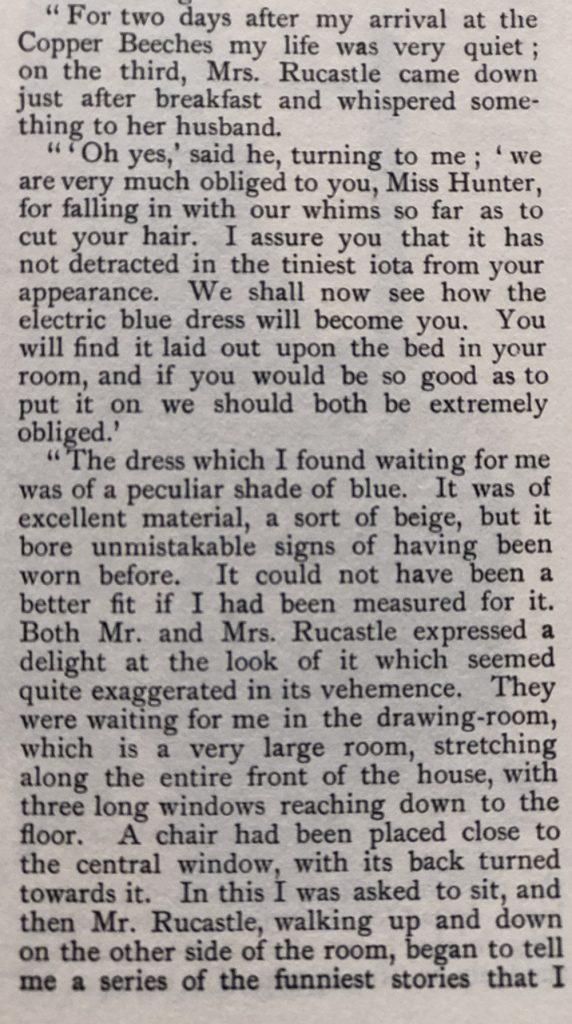

When I see that deliciously intense blue, I think of the Sherlock Holmes tale, The Adventure of the Copper Beeches. Violet Hunter, my absolute favorite female character out of all the Holmes stories, is asked by her new employer to don a mysterious blue dress. Doyle describes it as “electric blue,” and the reason behind her wearing it turns out to be nefarious indeed.

There’s nothing untoward in Mariana’s dress, however. Simply a sense that its wearer is worn out.

Mariana, from Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure, was rejected by her fiancee and was pining away in isolation. Once her dowry was lost at sea, she surrendered to seclusion.

Tennyson wrote about Mariana twice, first in his 1830 poem Mariana and again in Mariana in the South. The poet captured her sense of helplessness and loss. Millais then takes it further and expands the concept, showing her as she stretches in an attempt to ease her weariness, both physical and mental.

We hear more from the esteemed artist himself:

“The picture represents Mariana rising to her full height and bending backwards, with half-closed eyes. She is weary of all things, including the embroidery-frame which stands before her. Her dress of deep rich blue contrasts with the red-orange color of the seat beside which she stands. In the front of the figure is a window of stained glass, through which may be seen a sunlit garden beyond; and in contrast with this is seen, on the right of the picture, an oratory, in the dark shadow if which a lamp is burning.”

–The Life and Letters of Sir John Everett Millais (1899)

The stained glass windows facing Mariana in the painting were modeled on the actual windows from Merton Chapel, Oxford, shown in the photo below.

Did you, by chance, notice the little mouse in the corner of the painting? My snoopy loupe did.

All day within the dreamy house,

The doors upon their hinges creaked;

The blue fly sung in the pane; the mouse

Behind the mouldering wainscot shrieked,

Or from the crevice peered about.

Old faces glimmered through the doors,

Old footsteps trod the upper floors,

Old voices called her from without

–”Mariana,” Tennyson

Millais’ son recounts how that mouse portrayal came to be:

“But where was the mouse to paint from? Millais’ father, who had just come in, thought of scouring the country in search of one, but at that moment on obliging mouse ran across the floor and hid behind a portfolio. Quick as lightning Millais gave the portfolio a kick, and on removing it the poor mouse was found quite dead in the best possible position for drawing it.”

–The Life and Letters of Sir John Everett Millais (1899)

Other than the interloping mouse, Mariana is utterly alone.

There’s a verdant garden of growth beyond those windows, yet only dry, brittle leaves have infiltrated her sequestered world.

Like the Lady of Shalott, Mariana lives a secluded existence. Her isolation and sense of despair lends itself well to that particularly Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic. Among the many Isabellas, Ophelias, and endless Ladies of Shalott, Mariana fits right in with the tragic female stories depicted on the canvasses of the Pre-Raphaelite circle.

She only said, ‘My life is dreary-

He cometh not’ she said

She said ‘I am aweary, aweary –

I would that I were dead.’

– Mariana, Alfred, Lord Tennyson

Mariana is an evocative Pre-Raphaelite masterpiece that showcases Millais’ particular prowess. Filled with contrasting, vibrant hues and realism, Millais also packed in the perfect amount of details and symbolism to make it thrilling for the viewer to read the painting as one would a written narrative.

He not only invites you in, he takes you there. And a loupe enhances the experience.