Much of the Pre-Raphaelites’ work presents a narrative often inspired by literature and myth, but there are also a number of Victorian artworks are not just the telling of a story, but a depiction of a story being told.

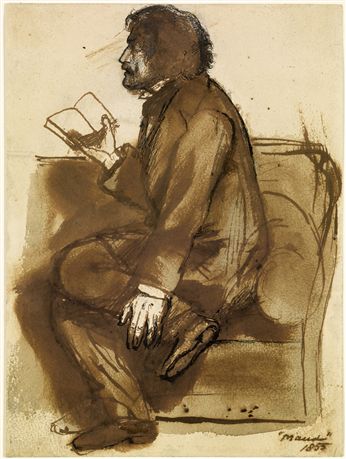

In the example above, Dante Gabriel Rossetti rapidly sketched Tennyson as he read his poem Maud to a group of friends.

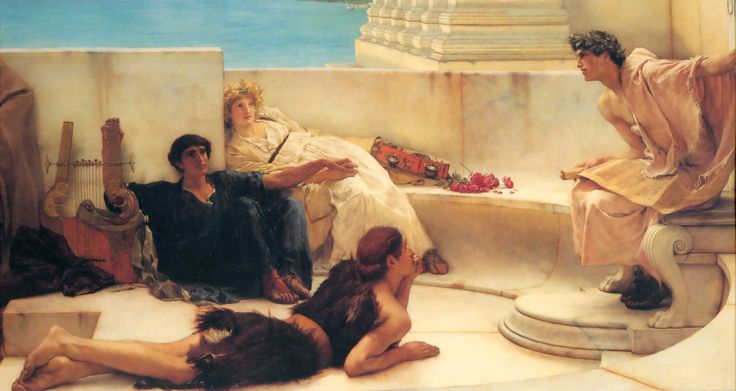

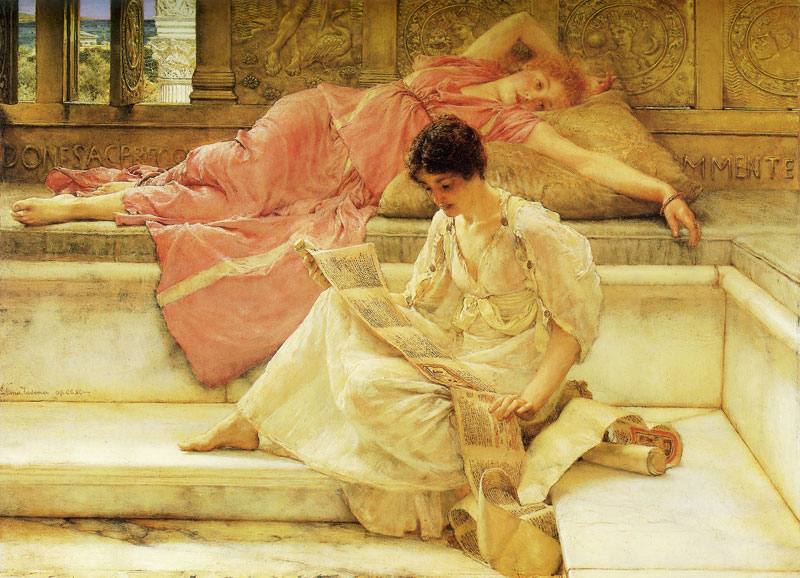

In the Alma-Tadema paintings below, we have two examples of a narrator/listener dynamic. The threesome listening to a reading of Homer is rapt and engaged. However, the single listener in The Favourite Poet presents a sort of languid attitude. Does the poetry inspire her or provoke thought and emotion? We can’t tell.

Perhaps my favorite example of storytelling in art is Sir John Everett Millais’ The Boyhood of Raleigh. You can see that the man is sharing the tale with gusto and physicality, he gestures strongly towards the sea. The two boys lean forward attentively and are absorbed in his words.

The Boyhood of Raleigh is not merely random boys listening to a story. It’s an example of how stories inspire and lead to great things.

One of the boys is intended to be a young Sir Walter Raleigh listening to an adventure of the sea and exploration.

F.G. Stephens, art critic and a founding member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, described Millais’ painting in a review the year it was released. “This work glows in the warm light of the Devonshire sun, and shows the sunburnt, stalwart, Genoese sailor – one of those who were half pirates, half heroes, such as Kingsley has delighted countless boys by describing – seated, with his brawny, bronzed shoulders towards us, on a sea wall, while before him, and at ease upon the floor, are Raleigh and his brother, listening eagerly and with rapt ears to the narration of wonders on sea and land.” (The Life and Letters of Sir John Everett Millais, vol. II)

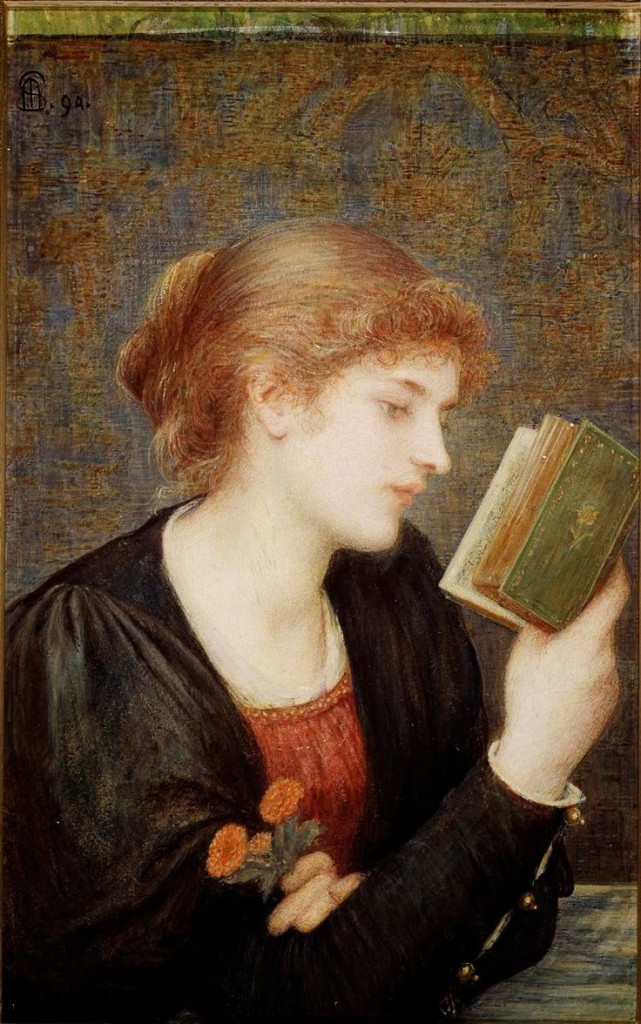

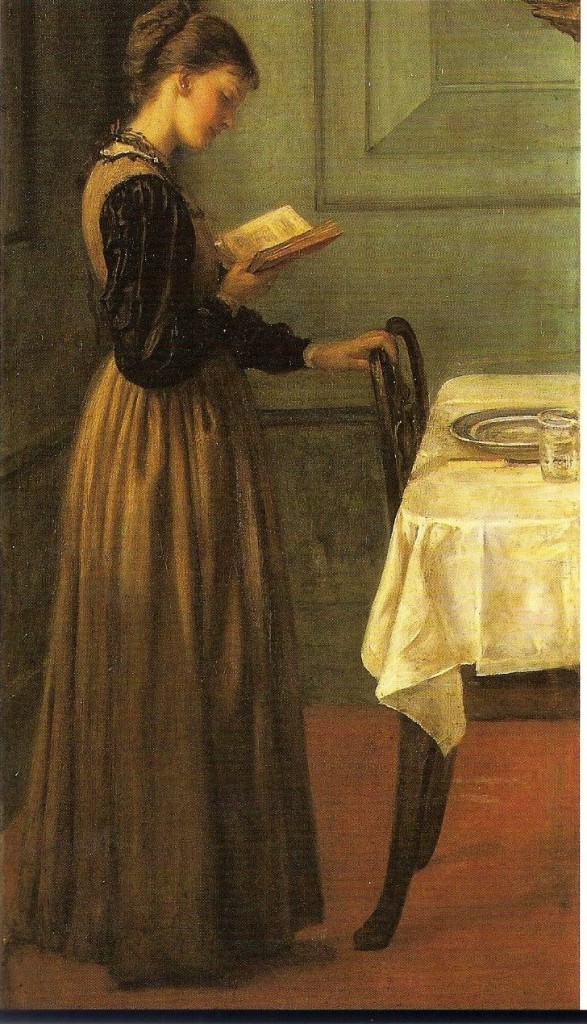

In contrast to paintings of stories being told to an audience, there are many Victorian examples of lone readers that evoke feelings of solitude and introversion.

There may seem to be no action in these works, but passionate readers will recognize what is hidden behind the stillness.The readers in these paintings are indulging in the purest form of escapism: the written word.

It is what you read when you don’t have to that determines what you will be when you can’t help it. –Oscar Wilde

Thanks for this excellent post

Thank you Marian!

I love the sketch of Tennyson reading Maud. It is so unposed, sitting on that couch in that casual way. You can just sense his excitement – ‘you’ve got to hear my new poem!’ I believe the evening was at the home of Robert and Elizabeth Browning. What a magical evening that must have been! It’s also interesting to think of Rossetti – he and the pre-raphaelites adored Tennyson’s work but you get the impression he kept them at arms length. This was probably a rare opportunity for Rossetti to meet his hero and maybe that’s why he made the sketch. Thanks for a wonderful post and some beautiful images. I like the Spartali Stillman as well. The image of the woman reading a book alone is a lovely one!

I agree! Rossetti’s sketch has a sense of urgency about it as if he was caught up in the moment and was desperate to capture Tennyson’s reading.