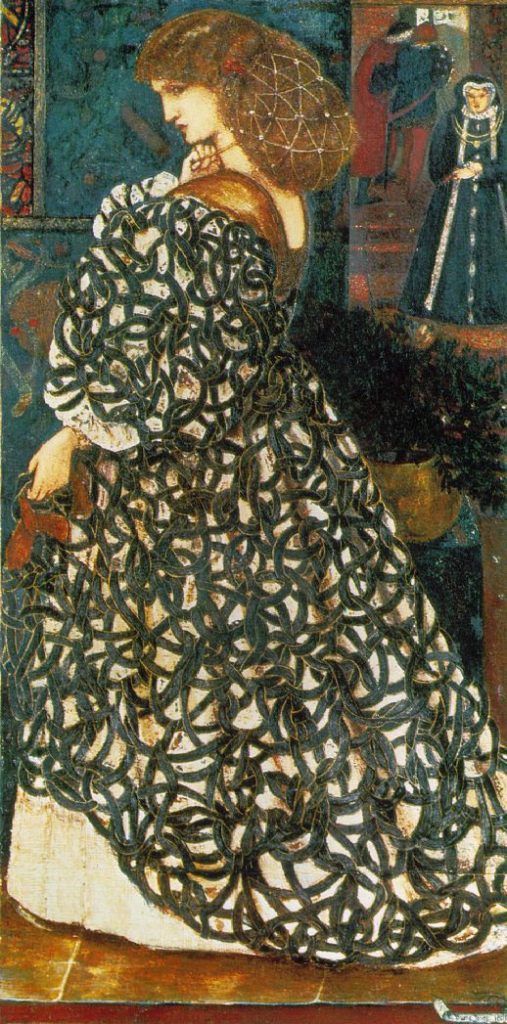

Fanny Cornforth was born Sarah Cox, the daughter of a blacksmith in Steyning. Later, she took on the name Fanny in honor of a younger sister who had died at a young age. Though she appears in some of Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s most majestic works, Fanny Cornforth is one of the most criticized and misunderstood Pre-Raphaelite models.

While attending a celebratory fireworks display held in honor of Florence Nightingale’s return from the Crimea, Fanny met the man who would change her life forever, Pre-Raphaelite artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Here’s where it gets dicey – there are two descriptions of how Fanny and Gabriel met. One is reasonably plausible; the other, while somewhat humorous, was clearly designed to paint Fanny in a certain light (pun intended).

The tale that has been most widely shared the most is this: Rossetti was visiting the fireworks exhibition at the Royal Surrey Gardens when he passed by a beautiful, busty blonde with a delightful Cockney accent. She cracked nuts with her teeth, spitting the shells at him.

This nutty account seems to have originated by poet William Bell Scott, who, although friends with Rossetti, was not there at the time. It was also repeated by Hall Caine, who did not enter Rossetti’s life until his later years.

Fanny’s version of their meeting was that Rossetti approached her and instantly loosened her hair, encouraging the locks to spill down her back. When Fanny’s cousin began to reprimand him, he explained that Fanny’s hair was so incredibly beautiful that he longed to paint it.

Given that we know that he excitedly approached Jane Morris and Alexa Wilding in similar ways (without actually dismantling their coiffures), this account seems reasonable.

Fanny has often been treated dismissively by scholars. Frequently described as a prostitute, it appears that most of the criticisms levied against her were based on her class and lack of education.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti had several models who were crucial to his work. Jane Morris captivated him with her dark, striking looks. Elizabeth Siddal was his idealized muse, put on a pedestal and revered, but Fanny was someone to experience life and laughter with, a woman to enjoy unashamedly.

Unfortunately for Fanny, she was not the woman Rossetti would marry.

She was distraught when Rossetti married Elizabeth Siddal, but as she always would, she forgave him and continued to appear in his work.

After the tragic and unexpected death of Siddal, Fanny eventually became Rossetti’s housekeeper. Since they were unmarried and since Fanny didn’t appear to try to make her life more respectable, she’s always carried the miasma of scandal.

Over time, her days as his muse waned as his eyes sought out a different type of beauty for his work, yet she would remain a permanent fixture in his life.

Fanny was nothing if not loyal, and her friendship was incredibly important to Rossetti. He gifted a great deal of his artwork to her and after his passing, she sold many of them to American collector Samuel Bancroft, which provided her security. Bancroft had an avid interest in the Pre-Raphaelites and developed a friendship with Fanny. Their correspondence, along with many letters between Rossetti and Fanny, can be viewed in the Delaware Art Museum’s digital collections.

Fanny was often ridiculed and overlooked by Rossetti’s family and friends, but she appeared to live life on her own terms as much as she could. She was brash and outspoken, but remained a true friend to Rossetti through his darkest times.

Fanny died at age 71 in Graylingwell Asylum. I encourage you to read Kirsty Stonell Walker’s poignant post about the discovery of Fanny’s final days.