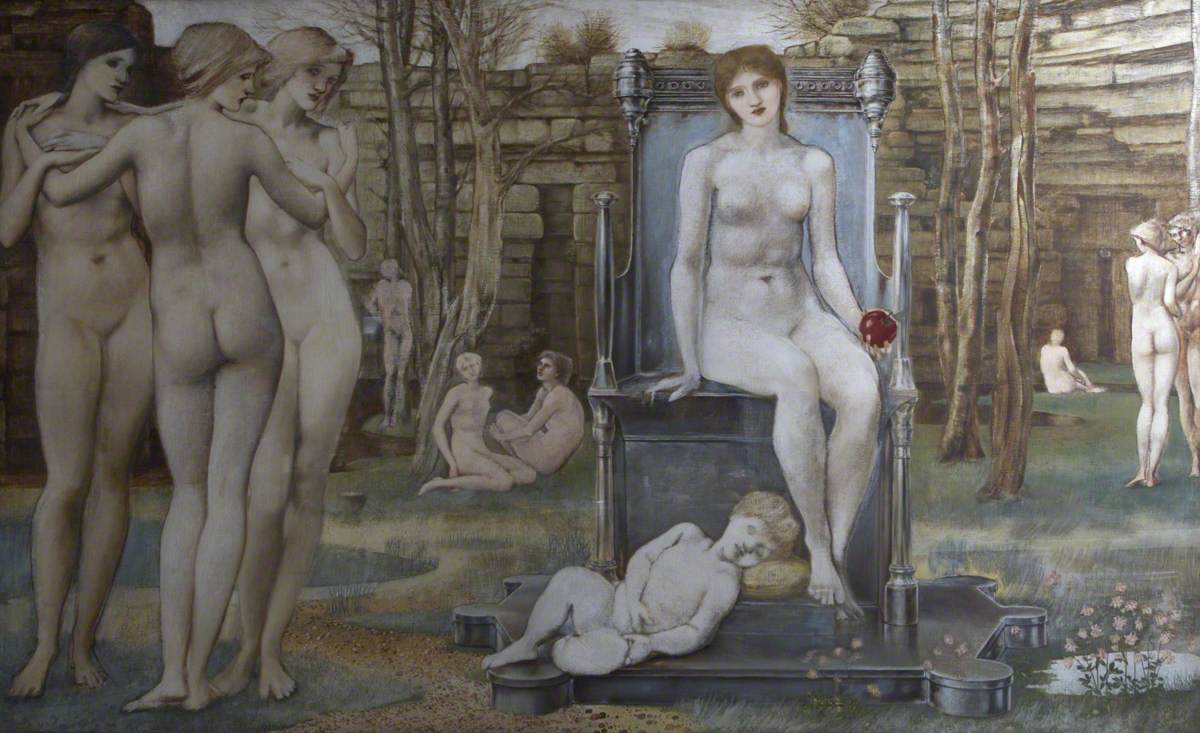

In her memorials of her husband, Georgiana Burne-Jones gives us a glimpse into the creation of Venus Concordia (pictured above).

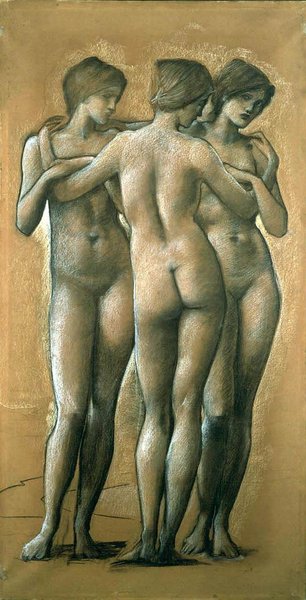

“After ‘The Fall of Lucifer’ was finished, ‘Venus Concordia’, long patiently waiting its turn, was taken up again. With the three Graces who stand together at the right hand of the Goddess Edward took endless pains, to make them beautiful in themselves, yet subordinate to the beauty of Venus. And again, the beauty of each one of them must be measured, none transcending the other. As he stood altering the outermost of the Graces one morning, he said: “In my anxiety to make it a good figure in itself, I’ve made it too independent of the others, and it’s become an isolates figure instead of part of the group, and that won’t do, we musn’t indulge in favorite passages in a work.” In the pencil design for this picture he had filled the background with happy lovers, a scheme which when he began to paint it he decided to alter. As he rearranged the figures he said: “They must be quieter than the people in the drawing are, and we cannot have so many of them. I musn’t make them too amorous either: Love’s asleep you see (he lies as a sleeping infant at his mother’s feet), and only Beauty is going on till he wakes up. They are waiting for him to wake up and then they can begin.” “Oh,” said Mr. Rooke, that’s what I had not noticed; did you always intend that?” E. “From the very first.”

–Memorials of Edward Burne-Jones, vol. I

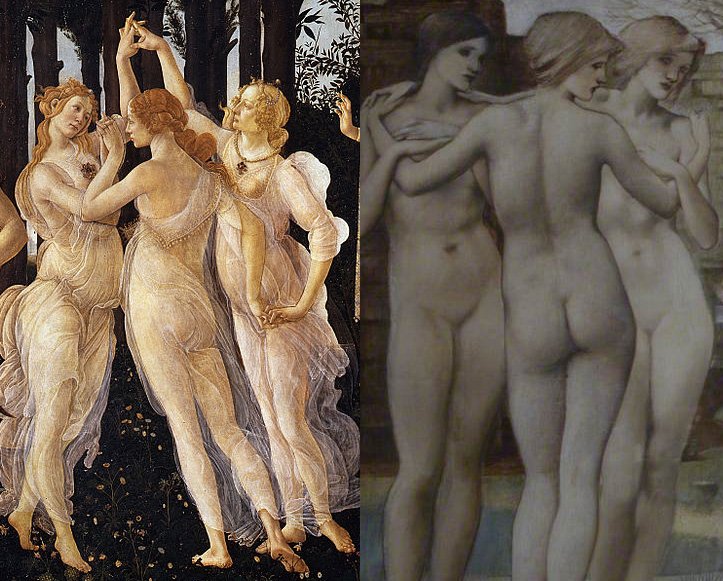

Venus Concordia’s three Graces have a certain similarity to Botticelli’s Graces in La Primavera.

Whenever I encounter the three Graces in art, they are almost always touching. They dance in tandem; they stand is if they are one body.

In writing about Venus Concordia, Georgiana Burne-Jones also took the opportunity to share her husband’s thoughts on how the human body is best portrayed.

The thought of ‘Venus Concordia’ with her attendant Graces recalls a saying of Edward’s about pictorial treatment of the human form: “A woman’s shape is best in repose, but the fine thing about a man is that he is such a splendid machine, so you can put him in motion, and make as many knobs and joints and muscles about him as you please.”

Which brings to my mind a sentence from John Berger’s Ways of Seeing which is, sadly, still true: “…men act and women appear.”