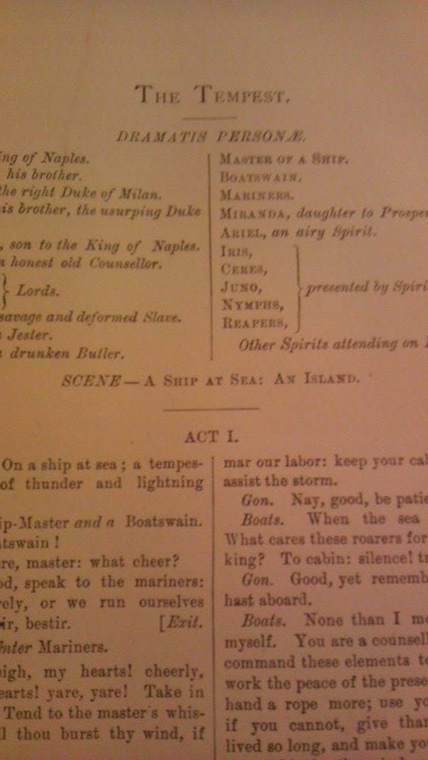

In The Tempest, Shakespeare tells us the story of Prospero, duke of Milan. Prospero was dethroned by his brother Antonio and abandoned at sea with his three year old daughter Miranda. Eventually they landed on an enchanted island, where the sole inhabitant is the creature Caliban. Prospero works his magic and places Caliban and all other spirits on the island under his control, including the spirit Ariel. Ariel is described as an ‘ayrie spirit’ (Air spirit) and was confined in a cloven pine by the witch Sycorax until Prospero broke the spell. Interestingly, Shakespeare isn’t clear about when Prospero became a sorcerer. Before or after landing on the island?

Years later, Prospero used his magic to create a tempest that caused his brother Antonio as well as Ferdinand, Sebastian, and others to become shipwrecked on the island.

When Millais painted Ferdinand he used fellow Pre-Raphaelite F.G. Stephens as his model. Stephens describes his experience posing for the painting in The Life and Letters of Sir John Everett Millais:

“In the summer and autumn of 1849 he [Millais] executed the whole of that wonderful background, the delightful figures of the elves and Ariel, and he sketched in the Prince himself. The whole was done upon a pure white background, so as to obtain the greatest brilliancy of the pigments. Later on my turn came, and in one lengthy sitting Millais drew my most un-Ferdinand-like features with a pencil upon white paper, making, as it was, a most exquisite drawing of the highest finish and exact fidelity. In these respects nothing could surpass this jewel of its kind. Something like it, but softer and not quite so sculpturesque, exists in the similar study Millais made in pencil for the head of Ophelia, which I saw not long ago, and which Sir W. Bowman lent to the Grosvenor Gallery in 1888.”

My portrait was completely modelled in all respects of form and light and shade, so as to be a perfect study for the head thereafter to be painted. The day after it was executed Millais repeated the study in a less finished manner upon the panel, and on the day following that I went again to the studio in Gower Street, where ‘Isabella’ and similar pictures were painted. From ten o’clock to nearly five the sitting continued without a stop, and with scarcely a word between the painter and his model. The clicking of his brushes when they were shifted in his palette, the sliding of his foot upon the easel, and an occasional sigh marked the hours, while, strained to the utmost, Millais worked this extraordinary fine face. At last he said, “There, old fellow, it is done!” Thus it remains as perfectly pure and as brilliant as then –fifty years ago– and it now remains unchanged. For me, still leaning on a stick and in the required posture, I had become quite unable to move, rise upright, or stir a limb till, much as I were a stiffened lay-figure, Millais lifted me up and carried me bodily to the dining-room, where some dinner and wine put me on my feet again. Later the till then unpainted parts of the figure of Ferdinand were added from the model and a lay-figure.”

The subject of the painting is Ferdinand, son of the King of Naples. When the King’s ship wrecks upon Prospero’s island, Ferdinand was separated from the rest of his shipmates. He was led by Ariel’s enchanting music to Prospero’s cell where he meets Miranda. Miranda believes him to be a spirit at first, ‘nothing natural I ever saw so noble’. Ferdinand speaks to her as ‘the goddess on whom these airs attend’.

Although not strictly a Pre-Raphaelite, the works of John William Waterhouse are definitely Pre-Raphaelite in style. He painted Miranda from The Tempest twice; both works depict her as she looks upon the storm created by her father.

The first one is beautiful, but his later Miranda is the most captivating. Waterhouse has captured the drama of nature, the waves exhibit the strength of the storm that will soon capsize the ship and its passengers. Miranda’s face is half-turned, so we can not read her expression. We can only use Shakespeare’s lines to learn her feelings:

If by your art, my dearest father, you have

Put the wild waters in this roar, allay them.

The sky, it seems, would pour down stinking pitch,

that the sea, mounting to th’ welkin’s cheek,

Dashes the fire out. Oh, I have suffered

With those that I saw suffer. A brave vessel

Who had, no doubt, some noble creature in her

Dashed all to pieces. Oh, the cry did knock

Against my very heart!

Thankyou for this!