While from the quivering bough the bird expands

His wings. And lo! thy spirit understands

(from A Vision of Fiammetta, Dante Gabriel Rossetti)

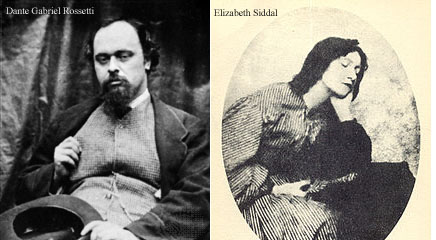

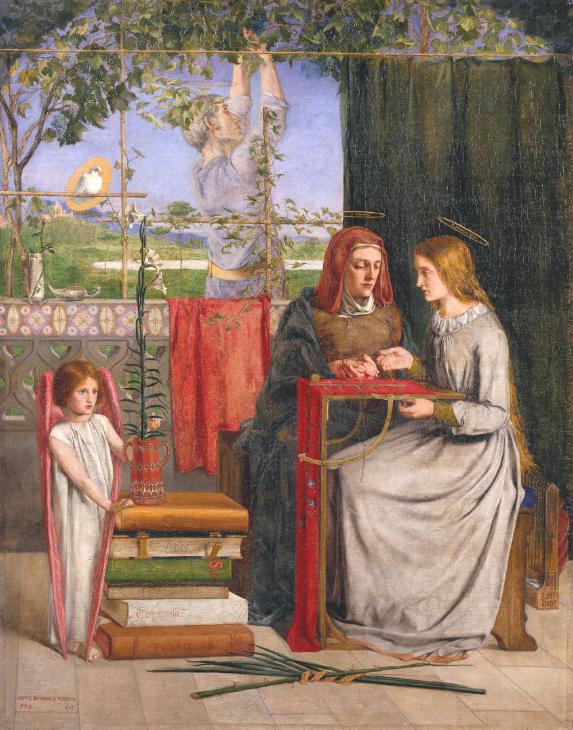

Birds appear frequently in both Rossetti’s paintings and poems. In the late 1860s, after his wife Elizabeth Siddal’s death, Rossetti began to be plagued by health and mental problems. A chaffinch landed on his hand while visiting poet William Bell Scott. Scott was apparently perplexed when Rossetti shared his belief that Lizzie’s spirit had migrated into the bird. Did Rossetti really believe that souls migrate into birds after death? Or was this a new notion, brought on by the stress of his ill health? At the time of this visit to Scott, Charles Augustus Howell (known as the worst man in London) was determining what steps were necessary to have Lizzie’s body exhumed in order to retrieve Rossetti’s poems. Perhaps viewing the bird as Lizzie allowed him to see her disinterment as not disturbing her in any way, as her soul was now flying free in the chaffinch.

In Beata Beatrix, his posthumous tribute to Lizzie, he paints her as Beatrice, Dante’s unrequited love in Vita Nuova. There is more than one version of this work. In one, a white dove brings Beatrice a red poppy. In another, the bird is red and the flower white. The poppy is significant due to the fact that Lizzie died of a Laudanum overdose. (Laudanum is an opiate which is derived from poppies. See Poppies: Sleep, Death, Remembrance.) In effect, the bird acts as a messenger that delivers into her hand the source of the substance that killed her.

‘Dove’ was one of Rossetti’s pet names for Lizzie. In a Valentine poem written for her, he calls her ‘dear dove divine’. He often drew a dove as a heiroglyph to represent her in letters. In one letter to his sister, poet Christina Rossetti, he mentions a black silk dress Lizzie had recently made for herself and calls her a “rara avis in terra,” quoting the Satires of the classical Roman poet Juvenal, who wrote of “a rare bird in the lands, and very like a black swan.”

In his soul/bird comment to William Bell Scott and in Beata Beatrix, birds seem to have supernatural significance to Rossetti. However, birds were prevalent in his work years prior to Lizzie’s death. In his 1855 poem, Beauty and the Bird, the inspiration was Victorian actress Ruth Herbert.

Beauty And The Bird

She fluted with her mouth as when one sips,

And gently waved her golden head, inclin’d

Outside his cage close to the window-blind;

Till her fond bird, with little turns and dips,

Piped low to her of sweet companionships.

And when he made an end, some seed took she

And fed him from her tongue, which rosily

Peeped as a piercing bud between her lips.

And like the child in Chaucer, on whose tongue

The Blessed Mary laid, when he was dead,

A grain,—who straightway praised her name in song:

Even so, when she, a little lightly red,

Now turned on me and laughed, I heard the throng

Of inner voices praise her golden head.

The poem was written around 1855, the drawing in 1858. Both predate his marriage to Lizzie Siddal, although it is interesting to note that bird in the drawing is a bullfinch and that Lizzie had a caged bullfinch as well. Interestingly, special attention is paid to the mouth, which she ‘flutes as when one sips’. Lips are often depicted in a distinctive style in Rossetti’s works. See Those Rossetti Lips.

In Veronica Veronese, a caged bird’s song inspires the composition of music. The painting includes a passage on the frame, written either by Rossetti or Swinburne and attributed to The Letters of Girolamo Ridolfi.”Suddenly leaning forward, the Lady Veronica rapidly wrote the first notes on the virgin page. Then she took the bow of the violin to make her dream reality; but before commencing to play the instrument hanging from her hand, she remained quiet for a few moments, listening to the inspiring bird, while her left hand strayed over the marriage of the voices of nature and the soul — the dawn of a mystic creation.”

Veronica Veronese is not merely a painting of a lovely woman, it is an allegory for the creation of art. The song of the bird is pure and organic and inspires her composition. In 1877, Walter Pater would famously say that “all art constantly aspires towards the condition of music.” Although this was said several years after Rossetti completed Veronica Veronese, it fits. Rossetti’s painting attempts to capture creativity in progress. Even though the Lady Veronica looks curiously languid for one who is in the midst of inspiration, the beginnings of art are largely internal. It is her soul and her mind that are inspired.

In A Sea-Spell, the bird does not inspire a human’s music. Instead, a sea-bird is mystically drawn to the tune of a siren. See The Lure of Water-Women.

In La Pia de Tolomei, Rossetti again visits the subject of Dante’s Vita Nuova. Jane Morris appears as Pia , who was found by Dante during his travel through Purgatory, where she remains since she has died without absolution. She says to Dante “remember me, the one who is Pia;

Siena made me, Maremma undid me:

he knows it, the one who first encircled

my finger with his jewel, when he married me”

The one who “first encircled my finger with his jewel” refers to her husband, Nello, who was responsible for her death so that he could marry a Countess. Nello imprisoned her in Pietra Castle, which is the scene we see in Rossetti’s painting. Rooks, omens of death, are flying in the background.

In 1871, Rossetti witnessed a flock of starlings during a visit to Kelmscott Manor that inspired his poem Sunset Wings.

To-night this sunset spreads two golden wings

Cleaving the western sky;

Winged too with wind it is, and winnowings

Of birds; as if the day’s last hour in rings

Of strenuous flight must die. (full poem here)

Perhaps one of Rossetti’s most beautiful poems that involves birds is Winged Hours:

Winged Hours

That wings from far his gradual way along

The rustling covert of my soul,—his song

Still loudlier trilled through leaves more deeply stirr’d:

But at the hour of meeting, a clear word

Is every note he sings, in Love’s own tongue;

Yet, Love, thou know’st the sweet strain wrong,

Through our contending kisses oft unheard.What of that hour at last, when for her sake

No wing may fly to me nor song may flow;

When, wandering round my life unleaved, I

The bloodied feathers scattered in the brake,

And think how she, far from me, with like eyes

Sees through the untuneful bough the wingless skies?

Symbolism abounds in Pre-Raphaelite art. For Rossetti, it seems that the use of birds is intensely personal as well as symbolic. His use of double meanings in both poetry and painting means that we can interpret his birds in multiple ways. Perhaps the artist himself never fully understood his frequent inclusion of them. Yet there they are, another enigmatic feature in Rossetti’s art. It is repetitive symbols such as these that keep pulling me back again and again into the mysterious and beautiful world of Dante Gabriel Rossetti.