In Love and Death (above) we see Death as a fully clothed adult whose face we cannot see. Love is depicted as a nude boy, vulnerable and exposed. When this painting was first exhibited in the Grosvenor Gallery in 1877, it was reviewed by Oscar Wilde:

‘a large painting, representing a marble doorway, all overgrown with white-starred jasmine and sweet briar rose. Death a giant form, veiled in grey draperies, is passing in with inevitable and mysterious power, breaking through all the flowers. One foot is already on the threshold, and one relentless hand is “tended, while Love, a beautiful boy with lithe brown limbs and rainbow coloured wings, all shrinking like a crumpled leaf, is trying, with vain hands, to bar the entrance. A little dove, undisturbed by the agony of the terrible conflict, waits patiently at the foot of the steps for her playmate, but will wait in vain, for though the face of death is hidden from us, yet we can see from the terror in the boy’s eyes and quivering lips, that Medusa-like, this grey phantom turns all it looks upon to stone; and the wings of love are rent and crushed.’ (Source)

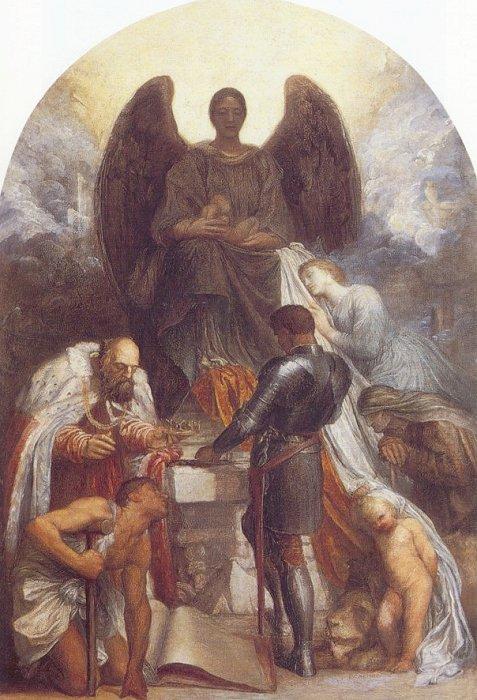

In The Angel of Death (above) Watts shows Death as the great equalizer that comes to us all. A wide variety of people appear before the stoic Angel of Death, including an infant, a knight, a king removing the crown he shall no longer need. This is an incredibly sad work that captures our human frailty in a beautiful and poignant way.

Pondering artistic representations of death may seem morbid, but I believe that there is power in exploring the mortality of our fragile existence.

All too often life has chaos to which we can bring no order. Death rarely comes when we expect it. Art is a mirror and images such as these give me a moment to reflect in a respectful way. In the midst of the chaos brought by tragedy and loss, art and literature can give us a structure through which to process pain.

The Victorian era birthed Industrialism and scientific discovery, yet people held firmly to superstition and folklore. Death closely hovered around every family, regardless of wealth or class.

Mourning was so common that there were societal rules about it that were to be strictly observed. When death is an almost palpable part of a culture, it is inevitable that it would be reflected in their literature and art.

Ghost stories and images of death were embedded in the fabric of Victorian life and neither science nor rational thought could inhibit the lure of a supernatural tale. Today our own cultural experience with death may be vastly different, yet perhaps in moments of grief, there is still solace to be found in Victorian imagery.

To die, to sleep–No more–and by a sleep to say we end the heartache, and the thousand natural shocks that flesh is heir to. ‘Tis a consummation devoutly to be wished. To die, to sleep–To sleep–perchance to dream: ay, there’s the rub, for in that sleep of death what dreams may come… –Hamlet, William Shakespeare

As usual, your essays bring to mind so many allusions to art, literature, and music that my mind races down one rabbit trail after another as I read. In this case, I cannot help but remember these lines from Thanatopsis by William Cullen Bryant:

So live, that when thy summons comes to join

The innumerable caravan, which moves

To that mysterious realm, where each shall take

His chamber in the silent halls of death,

Thou go not, like the quarry-slave at night,

Scourged to his dungeon, but, sustained and soothed

By an unfaltering trust, approach thy grave,

Like one who wraps the drapery of his couch

About him, and lies down to pleasant dreams.

Thank you much for posting that. Thanatopsis is such a beautiful and thought-provoking poem. In fact, it is one of the first poems that I fell deeply in love with when I was young. My grandmother had bought a very old volume of William Cullen Bryant’s poems at an estate sale. I loved the poem instantly. Because I was so young, I remember having to think a great deal on ‘the innumerable caravan which moves’ and what that could possibly mean. It’s a poem with the power to stay with you long after you have read it. As is his poem A Forest Hymn.

After viewing over 100 “death” paintings on the Art Renewal Center website (http://www.artrenewal.org), I have concluded that death is a subject better suited to poets than to artists. While I can appreciate the artistry of death-related paintings and even “like” a few, e.g. Gotch’s Death The Bride, not one reached out to grab my heart and physically constrict my chest and throat, let alone evoke a tear. I can think of a dozen poems about death which do just that. Two examples: The Mother And The Angel by Alexander Anderson (http://allpoetry.com/The-Mother-And-The-Angel); The Dead Lover by James Whitcomb Riley (http://www.poetry.net/poem/21052). I’m sure you can think of others.

While words could never do justice to the powerful imagery of La Ghirlandata or The Beloved, or to the deep human emotions conveyed by The Soul Of The Rose or Beata Beatrix, I have discovered that, at least for myself, poetry is a more powerful and appropriate medium for the subject of death.

P.S. If you are not already familiar with it, you may be interested in another Death The Bride painting by Lucien Levy-Dhurmer (1865-1953). His bride is a little creepier, but is still a recognizable rendition of the earlier painting by Gotch. http://www.artrenewal.org/pages/artwork.php?artworkid=15903