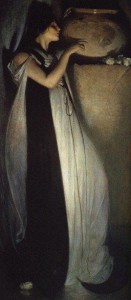

I think Sir John Everett Millais’ painting Speak! Speak! is a perfect Pre-Raphaelite image to share on Halloween. The ghost of a bride appears to her love. He reaches out to her, urging her to speak. It’s a haunting image and the concept had been on the artist’s mind for forty years before he began to paint it.

“The picture tells its own tale. It is that of a young Roman,who has been reading through the night the letters of his lost love; and at dawn, behold, the curtains of his bed are parted, and there before him stands, in spirit or in truth, the lady herself, decked as on her bridal night and gazing upon him with sad but loving eyes. An open door displays the winding stair down which she has come; and through a small window above it the grey dawn steals in, forming, with the light of the flaring taper at the bedside, a harmonious discord, such as the French school delight in, and which Millais used to good effect in his earlier picture, ” The Rescue”. — The Life and Letters of Sir John Everett Millais

Like his fellow Pre-Raphaelite artists, Millais took great pains to find just the right furniture and props to create Speak! Speak! You may be familiar with the extremes he took when painting Ophelia, where model Elizabeth Siddal posed in cold water for hours and grew quite ill as a result (I have an article about Siddal and Ophelia in the current issue of Shakespeare Magazine if you’re interested) For Speak! Speak! Millais purchased an old four-poster bed and attempted to borrow an antique lamp from a museum. Upon learning that borrowing the lamp was forbidden, the artist actually drew the object and had an iron worker create a perfect facsimile. Millais’ son remarked that from beginning to end of the work, his father took a romantic interest in the picture.

“Punch had an amusing note on the painting that Millais used often to chuckle over, the suggestion being that it represented a young man whose wife had run up a fearful bill for diamonds, and this so haunts him that he has a nightmare in which she appears in her finery.” –The Life and Letters of Sir John Everett Millais

The painting, for me, also brings to mind Wilkie Collins’ book The Woman in White. It’s one of my favorite Victorian mysteries and the author and Millais were great friends. Here Millais has created that same spectral presence of a startling woman in white. For more on The Woman in White and other paintings using the symbolism of white-clad ladies, see Gowns so White and Fair.

How They Met Themselves is an image of the uncanny, another perfect choice for All Hallow’s Eve. Here artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti explores the supernatural theme of doppelgangers. It is a curious work and he referred to it as his ‘bogie’ drawing. A pair of Medieval era lovers take a romantic walk in the woods, only to encounter themselves. According to lore, to see your doppelganger is a foreshadowing of your death. The original version of How They Met Themselves was inscribed with the dates 1851 1860, 1851 being the early days of his relationship with Elizabeth Siddal. They married in May of 1860 and she died two years later of a Laudanum overdose. Her life was quite sad towards the end because of their stillborn daughter and her struggle with addiction. Images such as Rossetti’s ‘bogie’ drawing and Millais’ Ophelia, which Siddal posed for, cement her in the public eye as being a death-like figure. The fact that Rossetti later had her exhumed doesn’t help. Upon her death, he had buried his manuscript of poems with her. She was exhumed seven years later so that he could publish them. This morbid act adds to her mystique, but overshadows her work. (SeeElizabeth Siddal: Laying the ghost to rest)

Today also happens to be the birthday of poet John Keats, whose work was so admired by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood that he was among those added to their list of ‘Immortals’, a list that served as a sort of creed and embodied great men whose works were inspirations to follow.

In the art of the Pre-Raphaelites, we see a marriage of visual art and literature. Their early works are filled with scenes from the literary world, taken from authors such as Shakespeare, Tennyson, and Keats. These works demonstrate the interconnection of artistic expression and the written word in a way that goes far deeper than merely illustrating the text. When they painted a depiction based on a Keats poem, they breathed life and brilliant color into the painting making it almost a synthesis of the poem itself. In William Holman Hunt’s Isabella and the Pot of Basil, we don’t see the backstory at all. We aren’t shown her lover Lorenzo, or her brothers who murdered him. But despite what is left out, the painting is a powerful one that my words fail to describe. In person it is arresting; Isabella is practically life size and she’s painted so vividly that I almost had to stop myself from reaching out to touch her face. The room she stands in beckons to you; the tiled floor looks as if it would be cold on your feet. The majolica pot, symbolically decorated with a skull, almost dares you to lightly touch it. Her lover’s head is buried inside. She embraces it, her hair mingling with the basil leaves. It’s a painting of all-consuming grief. It’s a painting that encompasses both life and death. And in this one work, Holman Hunt has touched upon the germ of Keats’ poem. In doing so, he keeps the poem alive. Viewers, having seen the painting, will return to the words. Readers, gripped by the poem, may seek the painting out. It’s a glorious cycle.

And she forgot the stars, the moon, and sun,

And she forgot the blue above the trees,

And she forgot the dells where waters run,

And she forgot the chilly autumn breeze;

She had no knowledge when the day was done,

And the new morn she saw not: but in peace

Hung over her sweet Basil evermore,

And moisten’d it with tears unto the core — John Keats

Other Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood posts that may tickle your Halloween fancy:

Did Elizabeth Siddal inspire Bram Stoker?

Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the Supernatural

Waterhouse’s Magic Circle and The Crystal Ball

More on Pre-Raphaelite art and John Keats:

Love, Death, and Potted Plants