Pre-Raphaelites sought fidelity to nature in their works, recreating the natural world with painstaking attention to detail. They did not, however, limit themselves to realistic subjects.

Their paintings often placed supernatural or fantasy subjects from mythology and literature into realistic settings. Such depictions with their vivid hues and photographic realism resulted in works that were startlingly original.

John Everett Millais’ Shakespearean painting of Ferdinand being lured by Ariel is a beautiful example of supernatural fantasy in Pre-Raphaelite art, for example.

Prior to the formation of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Dante Gabriel Rossetti was already captivated by supernatural themes and this can be seen in his own work throughout his life. His reading tastes skewed towards the supernatural.

In addition to an early love for Faust and Mephistopheles, Rossetti cut his teeth on tales such as Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué’s Undine, Wilhelm Meinhold’s books Sidonia the Sorceress and The Amber Witch, and stories by E.T.A. Hoffman. It is interesting to note that what many of these works have in common other than their supernatural theme is the use of a strong, important female character. Women are central figures in Rossetti’s own works, from his paintings to his writings of poetry and prose. In Hand and Soul, for example, he uses the supernatural figure of a beautiful woman to personify the human soul.

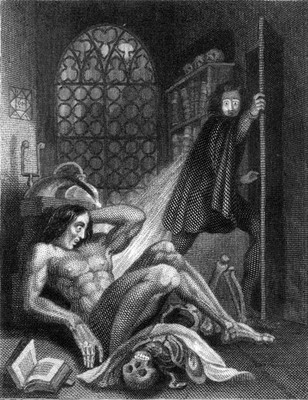

An early inspiration for Rossetti was the artist Theodore von Holst (1810-1844) whose works were frequently derived from macabre and supernatural stories.

Von Holst was the first artist to illustrate Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and he painted works based upon the writings of some of Rossetti’s favorite writers, including la Motte Fouqué. Rossetti described him as the ‘Edgar Poe of painting’, high praise indeed as Rossetti was enamored by the fantastic and macabre works of Poe.

Rossetti’s poem The Card-Dealer was inspired by von Holst’s painting The Wish, seen above.

Could you not drink her gaze like wine?/Yet though its splendour swoon/Into the silence languidly/As a tune into a tune,/Those eyes unravel the coiled night /And know the stars at noon. (Full poem here)

Rossetti also had a fondness for artist William Blake and in 1847, he purchased the deceased artist’s notebook after having borrowed the necessary ten shillings from his brother, William Michael Rossetti.

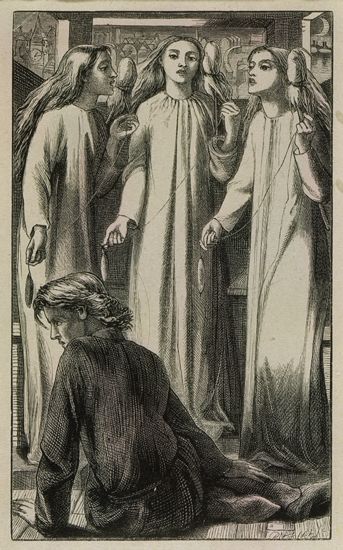

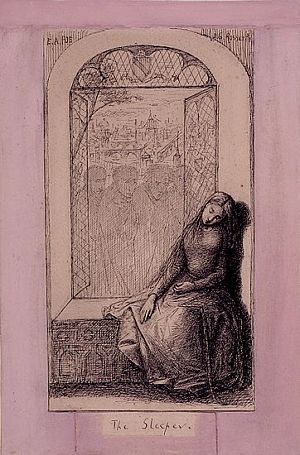

His appreciation for the works of Edgar Allan Poe prompted Rossetti to illustrate several Poe works including The Raven, The Sleeper, and Ulalume.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti was inspired by Edgar Allan Poe’s The Raven when he wrote The Blessed Damozel.

Poe alluded the subject of The Raven, saying “When it most closely allies itself to Beauty: the death then of a beautiful woman is unquestionably the most poetical topic in the world, and equally is it beyond doubt that the lips best suited for such topic are those of a bereaved lover.” This concept of beauty, death, and the separation of lovers was the impetus for Rossetti’s Blessed Damozel.

In 1860, while on his honeymoon with Elizabeth Siddal, Rossetti explored the supernatural theme of doppelgangers in his work How They Met Themselves, a curious image that he referred to as his ‘bogie’ drawing.

A pair of Medieval era lovers take a romantic walk in the woods, only to encounter themselves. According to lore, to see your doppelganger is a foreshadowing of your death.

The original version of How They Met Themselves was inscribed with the dates 1851 and 1860, 1851 being the early days of his relationship with Siddal.

They married in May of 1860 and she died two years later of a Laudanum overdose. Her life was quite sad towards the end because of their stillborn daughter and her struggle with addiction. Images such as Rossetti’s ‘bogie’ drawing and Millais’ Ophelia, which Siddal posed for, cement her in the public eye as being a death-like figure. (The fact that Rossetti later had her exhumed doesn’t help.)

Upon her death, he had buried his manuscript of poems with her. She was exhumed seven years later so that he could publish them. This morbid act adds to her mystique, but overshadows her work. (See Elizabeth Siddal: Laying the ghost to rest)

Supernatural and spiritual themes were explored by Rossetti on canvas as well as lyrically in his poems.

This spilled over from his creative life into his real one in the late 1860s as he attempted to communicate with his late wife through seances. He once believed that her spirit had migrated into a bird he encountered while visiting poet and friend William Bell Scott. (This story is shared in the previous blog post The Worst Man in London.)

This was a troubling time in Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s life and he was gripped by mental distress and paranoia. I don’t think his supernatural leanings were a comfort for him during this period. He claimed that Elizabeth Siddal would have given the poems buried with her back to him if it had been physically possible, yet I believe that having her exhumed haunted him. He made it quite clear that he did not want to be buried with her in Highgate Cemetery after his death.

Perhaps art had begun to imitate life in a disturbing way. Years earlier, Rossetti had made a study of Bonifazio’s mistress where an artist’s model dies while the artist paints her picture.

Neglecting her, the artist focuses solely on his creation until he finds out that she is dead and it is too late to save her. It can be seen as an eerie foreshadowing of his wife’s death. In fact, the sentiments he expressed when placing his poems in her coffin were that he had often been working on them instead of taking care of her.

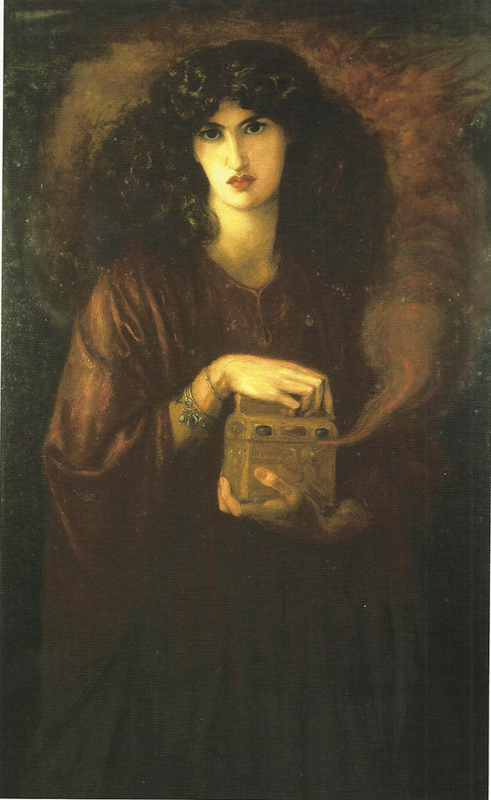

Through his early taste for supernatural fiction and art, it’s as if the young Rossetti was assembling an internal framework that would later inform his own work, resulting in paintings with a mysterious mixture of symbolism, beauty, and the fantastic. Chief among these is beauty because with Rossetti beauty was a religion.

His female forms symbolize more than human beauty of a physical nature.

When I look at Rossetti’s later works, it’s not just that they are paintings of women that he was sometimes involved with physically.

They represent beauty of a higher form, meant to be something that inspires and elevates our souls.

As I mentioned before, in Rossetti’s short story Hand and Soul the beautiful female form represents the soul of the artist itself. Perhaps this is beauty as a symbol for our own soul, beauty to be discovered within our true selves and then expressed as art. Don’t get me wrong, his later works are earthly delights, very physical and sensuous. Yet I still feel they carry his early idea of portraying the soul through beauty.

Tales of Rossetti’s romantic life often influence the way we look at his work. If you look at his many paintings of Jane Morris, for example, as only an artist’s paintings of his illicit paramour then you completely miss the larger message that it’s the appreciation and pursuit of beauty that transcends and transforms the human condition. The fact that he often mixes this notion of beauty with elements of the supernatural adds a somewhat poignant note to this message because it entwines beauty with death, something that Rossetti could not seem to escape and appears frequently in his work.