As I shared in The Magic Down the Rabbit Hole, immersing myself in a subject and following its trails is one of the biggest delights of my life. Since today is William Shakespeare’s birthday, I’m jumping headfirst into a few of my favourite Pre-Raphaelite works inspired by The Bard.

When listing Pre-Raphaelite images of Shakespeare, there are many to feast upon. So, for this post, I’m sharing three Shakespearean subjects that have led me down fascinating paths.

Let’s start with Millais’ painting of Portia and its connection to Dame Ellen Terry.

The model for Millais’ painting of Portia has often been incorrectly identified as Shakespearean actress Ellen Terry. The model was Kate Dolan, although the mistake was understandable as she was painted wearing Ellen Terry’s costume:

Of course I will lend you the dress (here it is.) or anything in the world that I possess, that could be of the very smallest service to you.

The dress was away in Scotland being cleaned for storing, or I should have sent it to you before–

Yours sincerely,

Ellen Terry

(Dated March 30, 1886)

Portia is the heroine of The Merchant of Venice. You may be familiar with one of her speeches:

The quality of mercy is not strain’d.

It droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven

Upon the place beneath. It is twice blest:

It blesseth him that gives and him that takes.

Reach across time and hear her perform as Portia in this 1911 recording.

It is Ellen Terry’s role as Lady Macbeth that captivates me, though. For one reason and one reason alone.

Her famous beetle-wing dress.

You may recognize it John Singer Sargent’s painting.

When it came to costuming, Dame Ellen Terry paid attention to the smallest detail. Her desire to create a gown for Lady Macbeth that would have a shimmering, serpent like appearance led to the design of this gown. Its iridescent green comes from thousands of beetle wings, a fragile affair that was recently restored.

As I read her memoirs, I was excited when I reached her performance as Lady Macbeth. The gown is so famous due to Sargent’s painting of it and I was eager to see if she would mention it.

I was not disappointed.

She not only mentions the dress, but gives a brief yet thrilling glimpse into the production.

Here is her description on Henry Irving as Macbeth:

“His view of “Macbeth”, though attacked and derided and put to shame in many quarters, is as clear to me as the sunlight itself. To me it seems as stupid to quarrel with the conception as to deny the nose on one’s face. But the carrying out of the conception was unequal.

When I think of his “Macbeth”, I remember him most distinctly in the last act after the battle when he looked like a great famished wolf, weak with the weakness of a giant exhausted, spent as one whose exertions have been ten times as great as those of commoner men of a rougher fiber and courser strength.

“Of all men else I have avoided thee.”

Once more he suggested, as only he could suggest, the power of Fate. Destiny seemed to hang over him, and he knew that there was no hope, no mercy.”

And the portion I was waiting for. Ellen Terry on the ‘Lady Macbeth’ gown:

“I am glad to think it is immortalized in Sargent’s picture. From the first I knew that picture was going to be splendid. In my diary for 1888 I was always writing about it:

“The picture of me is nearly finished, and I think it is magnificent. The green and blue of the dress is splendid, and the expression as Lady Macbeth holds the crown over her head is quite wonderful.”

Later, she continues:

“The picture is the sensation of the year. Of course opinions differ about it, but there are dense crowds round it day after day. There is talk of putting it on exhibition by itself.”

It was satisfying to see that she mentions Burne-Jones, a favorite artist of mine: “Sargent’s picture is almost finished, and it is really splendid. Burne-Jones yesterday suggested two or three alterations about the color which Sargent immediately adopted, but Burne-Jones raves about the picture.”

Further on, she shares her correspondence with her daughter concerning the gown:

From a letter I wrote to my daughter, who was in Germany at the time:

“I wish you could see my dresses. They are superb, especially the first one: green beetles on it, and such a cloak! The photographs give no idea of it at all, for it is in color that is so splendid. The dark red hair is fine. The whole thing is Rossetti- rich stained-glass effects, I play some of it well, but, of course, I don’t do what I want to do yet. Meanwhile I shall not budge an inch in the reading of it, for that I know is right. Oh, it’s fun, but it’s precious hard work for I by no means make her a ‘gentle, lovable woman’ as some of ’em say. That’s all pickles. She was nothing of the sort, although she was not a fiend, and did love her husband. I have to what is vulgarly called ‘sweat at it’ each night.”

The ‘Lady Macbeth’ gown has been mentioned online extensively:

Ellen Terry’s beetlewing gown back in limelight after £110,000 restoration

The Archeology of a dress

More on THAT dress: Victorian era dress, made with 1,000 beetle wings

And if the movie Brave is an indication, the ‘Lady Macbeth’ gown continues to inspire:

Terry was the great-aunt of actor Sir John Gielgud who describes her in his memoir: “She was a very Pre-Raphaelite actress. She had sat for painters like Rossetti, and she had known and talked with all the great men of her time–Tennyson, Browning, Ruskin, Wilde–and had learned a great deal from them. Yet she had a real humility. When you met her, you felt that she was ready to learn from children, or from anybody else with whom she came into contact. (Gielgud, John, An Actor and His Time, London: Sidgewick & Jackson, 1979)

Bring on the Ophelias

You can’t mention the Pre-Raphaelites and Shakespeare without talking about their many depictions of Hamlet’s ingenue Ophelia.

When John Everett Millais painted Ophelia he chose to depict her in the moments just before she drowns, a bold choice as most previous artists portrayed Ophelia before she ever enters the water. This isn’t the only striking aspect of his painting, however.

In the midst of this picture of death, the plant life is rich and colorful.

Each plant, whether background or foreground, is given equal attention and no detail is spared. The botanical aspects of Ophelia are so important that Millais chose to paint the background prior to adding in the figure, which was a very unusual move.

Elizabeth Siddal posed as Ophelia and developed pneumonia while laying in a bathtub. You can learn more about her at my website LizzieSiddal.com, my thoughts on the fifteenth anniversary of the site, and a recent tribute written in honor of her birthday.

It’s safe to say both Elizabeth Siddal and the character of Ophelia have been the greatest rabbit holes of my life.

While Millais’ Ophelia is dear to my heart, the Pre-Raphaelites gave us several Ophelias to choose from, only a few of which I will share here.

The play’s the thing…

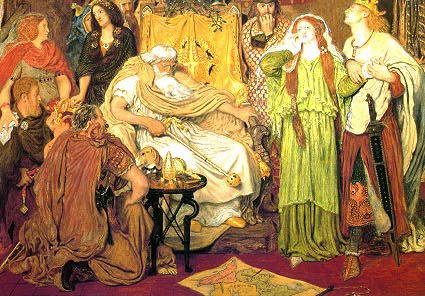

Ford Madox Brown’s paintings of King Lear excite me, because they were born from the passion of a viewer who was captivated by the performance of the play. Lucinda Hawksley describes this in Essential Pre-Raphaelites:

“Ford Madox Brown’s fascination for Shakespeare’s King Lear began in 1843 (reputedly after seeing William Charles Macready playing Lear on the London stage). Brown began to sketch scenes from the play feverishly — producing 16 in one year. Henry Irving, who later played Lear to great acclaim, became the owner of several of these.”

I blogged about this when Carrie Fisher died because this is the kind of tale that resonates with me deeply.

An artist was swept away by an outstanding performance, a performance that inspired him to feverishly create his own images of the saga.

Today, most of us see movies more often than a live production. When we want, we can easily own the movie for us to watch again and again.

What of Ford Madox Brown’s experience? A play is a different animal entirely. Performances differ from night to night; with each new audience a new experience is created.

Brown’s work as an attempt to capture what was inspired by that one performance. He may not have painted the exact actors, scenery or costumes from that performance, but he painted the passion for the story of King Lear that the performance inspired.

In Will of the World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare, author Stephen Greenblatt proposes that Shakespeare was possibly contemplating retirement –and thinking about its perils– when he wrote King Lear. “The tragedy is his greatest meditation on extreme old age; on the painful necessity of renouncing power; on the loss of house, land, authority, love, eyesight, and sanity itself.” Greenblatt describes it well. It is one of the most tumultuous Shakespearean dramas I have ever seen.

I’ve read King Lear in its entirety. It is a beautiful text to read, but I was left feeling somewhat dissatisfied. Shakespeare did not write his plays to be read, he wanted them to be seen, fully experienced by the senses.

I wanted to be involved in the story as Ford Madox Brown was. Searching for an adaptation to watch, I was happy to find a production of King Lear starring Sir Ian McKellen. It is a masterful performance with a talented ensemble. I’m not alone in my admiration of it — visitor comments on the PBS Great Performances page describes King Lear as a “life-altering experience, proving, once again, how great art presented intimately and at home, can illuminate the intricacies of a classic play in startling new ways.” Reading Shakespeare can be a beautiful experience, but it can never be the same as seeing it performed. Not just performed, but performed well.

There is a life cycle to art and creativity. Shakespeare continues to inspire. As do the Pre-Raphaelites. Since starting this website, I have been lucky enough to have met many people whose work is often a nod to the Pre-Raphaelites and their associates. I love Ford Madox Brown’s representations of King Lear because it is a perfect example of how someone’s creativity will stimulate the inventiveness of others. In Act 1, Scene 1 of King Lear, Shakespeare wrote that “Nothing will come of nothing.”

It is my firm belief that Art will come from Art.

***

Interested in more about Pre-Raphaelite art and Shakespeare? I wrote an article about Elizabeth Siddal and Ophelia in this issue of Shakespeare magazine. It’s free to read online. You can follow also Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood on Facebook and Twitter.