Inspired by artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s passion for wombats, every Friday is Wombat Friday at Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood. “The Wombat is a Joy, a Triumph, a Delight, a Madness!” – Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Thaddeus Fern Diogones Wombat is a willing assistant here at Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood. Sure, he can be easily distracted and he has a tendency to hide when I need him most but, for the most part, he’s a wombatty delight. He definitely wants to learn as much as he can about the Pre-Raphaelites, so together we are going to explore Millais a bit.

T-Dub is also a romantic wombat, so I thought he might enjoy a few stories of unselfish love. The paintings I’ve shared here today were described in The Life and Letters of Sir John Everett Millais as follows:

“The Huguenot” was the first of a series of four pictures embracing “The Proscribed Royalist”, “The Order of the Release” and “The Black Brunswicker”, each of which represents a more or less unfinished story of unselfish love, in which the sweetness of woman shines conspicuous.

The full title of the painting is actually A Huguenot, on St. Batholomew’s Day Refusing to Shield Himself from Danger by Wearing the Roman Catholic Badge. Try saying that three times fast.

Huguenots were French Protestants and in the 1570s, they ran the risk of death if they did not masquerade as Catholics by wearing a cross on their hats and a white band on their arm. Here the Huguenot, even as he gazes into his love’s eyes and gently cradles her head, steadfastly refuses the white band.

The model for the Huguenot was Major-General Arthur Lempriere, who said :

“It was a short time before I got my commission in the Royal Engineers in the year 1853 (when I was about eighteen years old) that I had the honour of sitting for his famous picture of ‘The Huguenot’. If I remember right, he was then living with his father and mother in Bloomsbury Square. I used to go up there pretty often and occasionally stopped there. His father and mother were most kind.

“After several sittings I remember he was not satisfied with what he had put on the canvas, and he took a knife and scraped my head out of the picture, and did it all again. He always talked in the most cheery way all the time he was painting, and made it impossible for one to feel dull or tired. I little thought what an honour was being conferred on me, and at the time did not appreciate it, as I always have since.”

The girl in ‘The Huguenot’ was Anne Ryan, who also posed in The Proscribed Royalist. She’s a mystery I will probably never solve. Just take a look at this passage written by Millais’ son.

“A lovely woman (Miss Ryan) sat for the lady in “The Huguenot”, Mrs. George Hodgkinson, the artist’s cousin, taking her place on occasion as a model for the left arm of the figure. Alas for Miss Ryan! her beauty proved a fatal gift: she married an ostler, and her later history is a sad one. My father was always reluctant to speak of it, feeling perhaps that the publicity he had given to her beauty might in some small measure have helped (as the saying is) to turn her head.”

What was Miss Ryan’s sad history? What was so terrible that Millais would never speak of it and his son would only allude to it in the book? (T-Dub is beginning to form ideas here which I feel are wholly inappropriate for a young wombat. He is prone to flights of fancy.)

As mentioned, Miss Ryan also appears in the next painting of the series, The Proscribed Royalist.

Writing about the painting, Millais said:

I have a subject that I am mad to commence (The Proscribed Royalist), and yesterday took lodgings at a delightful little inn near a spot exactly suited for the background. I hope to begin painting Tuesday morning, and intend working without coming to town at all till it is done. The village is so very far from any railway station that I have no chance of getting to London in rainy weather. My brother is going to live with me part of the time, so I shall not be entirely a hermit.

Millais and his brother stayed at “George Inn” at Bromley and they made quite an impression on the innkeeper, Mr. Vidler. Mr. Vidler was apparently very proud of his signboard, a representation of St. George slaying the dragon. A storm severely damaged the sign and the Millais brothers painted him a new one. Flattered by the large number of people who admired the new sign, from then on Mr. Vidler made a point to bring the sign in at night for safety.

Artist Arthur Hughes posed for the Royalist. At this point, the background was finished and Hughes posed in the Millais home on Gower Street.

The Proscribed Royalist, 1651 (1853) is a painting by John Everett Millais which depicts a young Puritan woman protecting a fleeing Royalist after the Battle of Worcester in 1651, the decisive defeat of Charles II by Oliver Cromwell. The Royalist is hiding in a hollow tree, a reference to a famous incident in which Charles himself hid in a tree to escape from his pursuers. Millais was also influenced by Vincenzo Bellini‘s opera I Puritani.

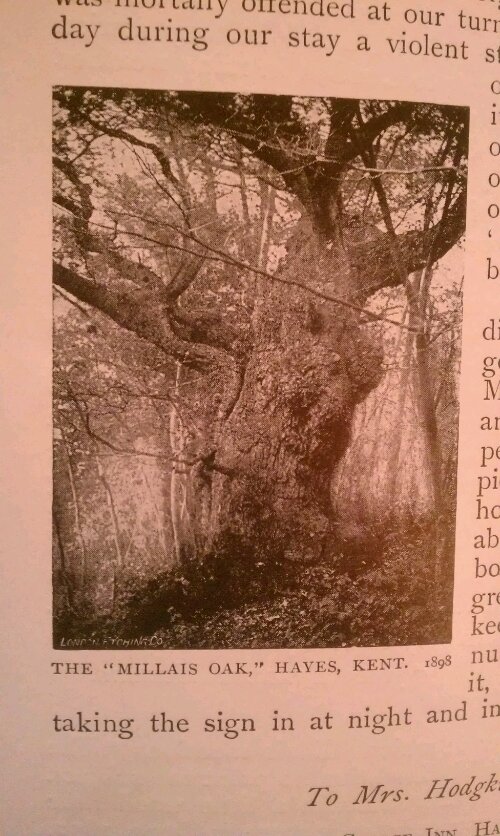

Millais painted the picture in Hayes, Kent, from a local oak tree that became known as the Millais Oak (Wikipedia)

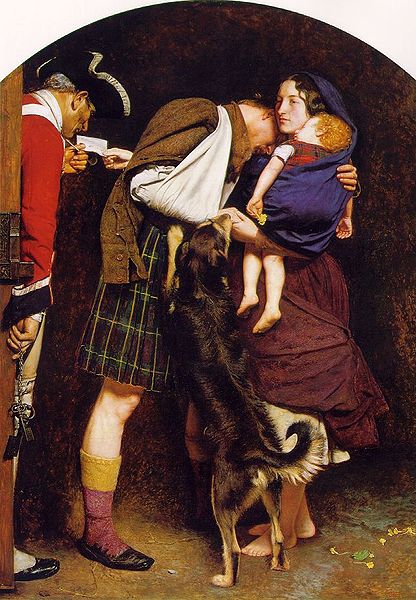

The next picture is The Order of Release. It’s significant because Millais used his future wife Effie as a model, but at this point in time she was married to art critic John Ruskin. In The Huguenot, the woman desires to protect her love. In The Proscribed Royalist, she secrets him away. In The Order of Release, she delivers the necessary order for her husband (a Scottish Highlander) to be released from prison.

It seems the only difficulty Millais had with this painting was the child and the dog. “All the morning I have been drawing a dog, which in unquietness is only to be surpassed by a child. Both of these animals I am trying to paint daily, and certainly nothing can exceed the trial of patience they occasion. The child screams upon entering the room, and when forcibly held in its mother’s arms struggles with such successful obstinacy that I cannot begin my work until exhaustion comes on, which generally appears when daylight disappears.”

Several fashionable ladies claimed to be the model for the female while five or six distinguished officers boasted that they posed for the Brunswicker. Charles Dickens’ daughter Kate (later Kate Perugini) was the sole model for the sweetheart and a private soldier from the Albany Street Barracks was the Brunswicker. According to Millais, the pair never posed together. The soldier posed with a lay-figure. Kate posed against a man of wood.

“I made your father’s acquaintance when I was quite a young girl. Very soon after our first meeting, he wrote to my father asking him to allow me to sit to him for a head in one of the pictures he was then painting, ‘The Black Brunswicker’. My father consenting, I used to go to your mother and father’s house, somewhere in the North of London, accompanied by an old lady, a friend of your family. I was very shy and quiet in those days, and during the ‘sittings’ I was only too glad to leave the conversation to be carried on by your father and his old friend; but I soon grew to be interested in your father’s extraordinary vivacity, and the keenness and delight he took in discussing books, plays, and music, and sometimes painting–but he always spoke less of pictures than of anything else– and these sittings, to which I had looked forward with a certain amount of dread and dislike, became so pleasant to me that I was heartily sorry when they came to an end and my presence was no more required in the studio.

As I stood upon my ‘throne’, listening attentively to everything that passed, I noticed one day that your father was much more silent than usual, that he was very restless, and a little sharp in his manner when he asked me to turn my head this way or that. Either my face or his brush seemed to be out of order, and he could not get on. At last, turning impatiently to his old friend, he exclaimed, ‘Come and tell me what’s wrong here, I can’t see anymore, I’ve got blind over it.’ She laughingly excused herself, saying she was no judge, and wouldn’t be of any use, upon which he turned to me. ‘Do you come down, my dear, and tell me’, he said. As he was quite grave and very impatient, there was nothing for it but to descend from my throne and take my place beside him. As I did so I happened to notice a slight exaggeration in something I saw upon his canvas, and told him of it. Instantly, and greatly to my dismay, he took up a rag and wiped out the whole of the head, turning at the same time triumphantly to his old friend. ‘There! that’s what I always say; a fresh eye can see everything in a moment, and an artist should ask a stranger to come in and look at his work, every day of his life. There! get back to your place, my dear, and we’ll begin all over again!–Kate Dickens Perugini in The Life and Letters of Sir John Everett Millais

Clad in a ballgown, a young sweetheart tries to stop her love from leaving for battle. One hand on his chest, the other attempting to close the door as he opens it. Millais described the painting as the “perfect pendant for The Huguenot“. It seems as if the striking Brunswickers uniforms were what made an impression on Millais. Solid black with a death’s head and cross-bones, I can see why it lit his imagination.

They were nearly annihilated but performed prodigies of valour… I have it all in my mind’s eye and feel confident that it will be a prodigious success. The costume and incident are so powerful that I am astonished it has never been touched upon before. (Sir John Everett Millais)

Each of these paintings is a story without an end, a mere slice of a tale. The outcomes are as secret to us as the fate of model Anne Ryan. What happened to the Huguenot? Did the Royalist escape? Can we assume the family in The Order of Release lived out the rest of their days without further tragedy? Could the Brunswicker have returned to his lover, unscathed by the battle? Ultimately, we will just have to be satisfied with the mere glimpse Millais gave us of these unfinished stories of unselfish love.