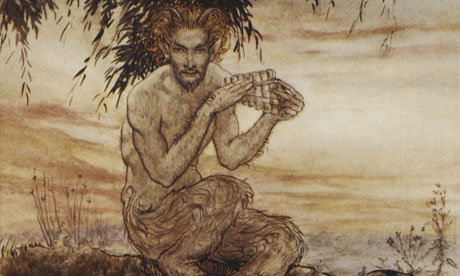

Above is a detail from Arthur Rackham’s illustration of Pan from The Wind in the Willows.

I first became enchanted by Pan when, as a little girl, I read The Wind in the Willows. I was in love with that book from the moment Mole became fed up with his spring-cleaning, left his hole, and met Ratty. Theirs is a beautiful friendship to read about, their trials with the flighty and conceited Toad, dangerous adventures in the Wild Wood, and their friendship with wise and solid Badger swept me away. And then Kenneth Grahame dropped that seventh chapter on me and I was never the same.

Pan’s appearance in The Piper at the Gates of Dawn,the seventh chapter, is not an incident that is crucial to the plot. In fact, it is frequently left out in abridged and adapted versions. Yet every time I encounter a fellow Wind in the Willows fan, they know that chapter, that moment. The quiet beauty of it lurks in their memory. I don’t care how long ago you read it, the magic is still there.

***

“This is the place of my song-dream, the place the music played to me,” whispered the Rat, as if in a trance. “Here, in this holy place, here if anywhere, surely we shall find Him!”

Then suddenly the Mole felt a great Awe fall upon him, an awe that turned his muscles to water, bowed his head, and rooted his feet to the ground. It was no panic terror – indeed he felt wonderfully at peace and happy – but it was an awe that smote and held him and, without seeing, he knew it could only mean that some august Presence was very, very near. With difficulty, he turned to look for his friend, and saw him at his side cowed, stricken, and trembling violently. And still there was utter silence in the populous bird-haunted branches around them; and still the light grew and grew.

Perhaps he would never have dared to raise his eyes, but that, though the piping was now hushed, the call and the summons seemed still dominant and imperious. He might not refuse, were Death himself waiting to strike him instantly, once he had looked with mortal eye on things rightly kept hidden. Trembling he obeyed, and raised his humble head; and then, in that utter clearness if the imminent dawn, while Nature, flushed with fullness of incredible colour, seemed to hold her breath for the event he looked in the very eyes of the Friend and Helper; saw the backward sweep of the curved horns, gleaming in the growing daylight, saw the stern, hooked nose between the kindly eyes that were looking down on them humorously, while the bearded mouth broke into a half-smile at the corners; saw the rippling muscles on the arm that lay across the broad chest, the long supple hand still holding the pan-pipes only just fallen away from the parted lips; saw the splendid curves of the shaggy limbs disposed in majestic ease on the sward; saw, last of all, nestling between his very hooves, sleeping soundly in entire peace and contentment, the little round, podgy, childish form of the baby otter. All this he saw, for one moment breathless and intense, vivid on the morning sky; and still, as he looked, he lived; and still, as he lived, he wondered.

“Rat!” he found breath to whisper, shaking. “Are you afraid?”

“Afraid?” murmured Rat, his eyes shining with unutterable love. “Afraid! Of Him! O, never, never! And yet- and yet- O, Mole, I am afraid!”

Then the two animals, crouching to the earth, bowed their heads and did worship. –(The Wind in the Willows, Kenneth Graham)

See how glorious that is? I don’t see why or how any parent could give their child an adapted version of that book. That chapter challenged me and as an eager reader I was hungry for that challenge. I did not fully understand it yet at the same time, I was captivated. That is the moment every avid reader delights in. And through the magic of reading, I can revisit that moment every time I re-read it. Touch the page, read the words and suddenly I am nine-year-old Stephanie Graham again and the feeling, the memory, is fresh. This is how books become friends. Books are time travel.

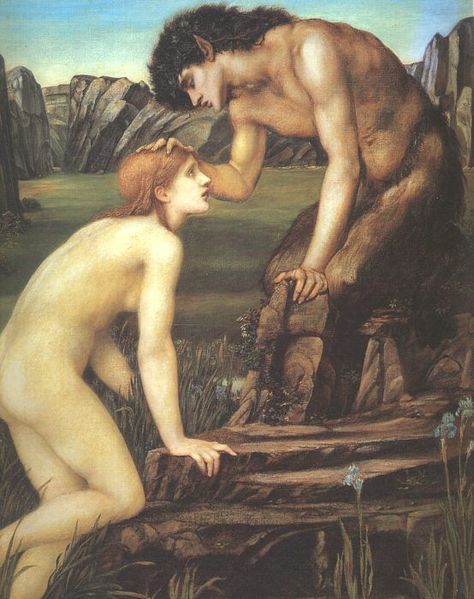

If you have ever read about Pan, you know there is another, much more adult interpretation of this demigod. I’m not going to go into his, ahem, scandalous side here. Instead, I’d like to stay true to the literary notions of Pan that first awakened the same unutterable love in me that Ratty experienced. The image of Pan and Psyche (above) is both beautiful and vulnerable. When Psyche is distraught over the loss of her love Eros, she attempts suicide in a river. She survives and the god Pan offers her comfort and advice.

Poet John Keats, who was a great inspiration to the Pre-Raphaelites wrote about Pan in Endymion. You can read the full text of his Hymn to Pan here.

In Waterhouse’s A Hamadryad, Pan appears younger and less overtly sexual as he plays his pipes for a hamadryad, a nymph that is destined to live and die with her tree. The Dryad is a supernatural being but she is still subject to the laws of nature. She will live a magical life, one with the forest until her tree dies.

Perhaps she hears him every morning until the day her tree reaches the end of its life cycle. Or perhaps his music has drawn her out from her tree. In many myths Pan as a sexual predator who respects no boundaries. But the depiction of him as a benevolent figure who plays his pipes to usher in the beauty of nature as he did in The Wind in the Willows enchants me.

He is a figure that represents the natural world and as such, he must know both light and dark, the beautiful and the ugly. If he can appreciate the sensuous, can he not also appreciate the innocent? He understands the ephemeral nature of the leaves that one day are lush and green and, months later, fall red and brittle on the forest floor. I believe this transience is what Sir John Everett Millais sought to capture in Autumn Leaves, Nature has its cycle. Perhaps Pan plays a small, yet significant, part in it. Authors like Keats and Grahame used him beautifully to illustrate their own reverence for the natural world. He appeals to me as much now as he did when I was nine. Let me hear your sweet pipings, Pan, for perhaps they usher in the dawn.

“All this he saw, for one moment breathless and intense, vivid on the morning sky; and still, as he looked, he lived; and still, as he lived, he wondered.” –The Wind in the Willows

In my absolutely biased opinion, that chapter is one of the finest things ever written in the English language.

I absolutely, wholeheartedly agree.

I love that Chapter in the Wind in the Willows. Where Mole and Ratty find the little Otter.

I still read it now and I am 58.

I love that Chapter it still gives me goosebumps when I read it