Fatima was painted by Sir Edward Burne-Jones in 1862 and depicts the last wife of Bluebeard, the ancient serial killer who has the bodies of his previous wives hidden away. Written by Charles Perrault, the story of Bluebeard was originally published in 1697.

Bluebeard hails from the days when children’s tales were gruesome, often cautionary, tales. Burne-Jones approaches the subject of Mrs. Bluebeard as she prepares to unlock the closet forbidden to her. He captures the suspense of the moment, since she has not yet entered and we know that on the other side of the door, according to the story, lies a “floor all covered over with clotted blood, on which lay the bodies of several dead women, ranged against the walls”

Using the forbidden key, she literally unlocks her husband’s secret.

Georgiana Burne-Jones described the painting in two letters to John Ruskin:

He has begun a water-colour, which he does not mean to make more than a sketch, of Bluebeard’s wife putting the key in the closet door. It is a tall, narrow picture, only containing Mrs. Bluebeard with a long passage behind her down which she has come–and the door, of course. Edward is sitting by, and has just looked up to charge me not to tell you about Bluebeard’s wife, because you will think the skeletons are the principal features. I reply that his warning comes too late, for I have told you, but that you will think nothing of the kind, and know as well as I do that it is only the picture of Fatima.”

She briefly mentions Fatima in her next letter to Ruskin:

Bluebeard’s wife has grown apace since I gave notice of her beginning, and is almost all that her friends could wish her–at least they are polite enough to say so, and now Ned has begun a smaller water-colour of Love flinging open a lady”s window in the early morning on St. Valentine’s Day and greeting her. Love bears her a little letter in his hand.

Interesting that Burne-Jones was reluctant for his wife to mention the picture, lest Ruskin think the skeletons would be the main feature. I assume that he wanted to avoid depicting the gruesome aspect of the story and focus on the bride herself in the moment before she discovers the truth.

In contrast with other Pre-Raphaelite works and their heavily detailed backgrounds, I find the use of simplicity in Fatima to be quite effective. It enables us to focus on how alone she is and the danger of her situation. The dark corridor behind her and the narrow size of the painting itself gives a sort of tunnel vision effect. Fatima alone commands our attention.

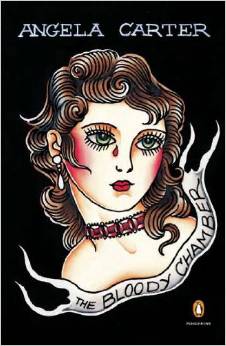

Every generation has their Bluebeard. Personally, as I look at Burne-Jones’ Fatima it is with Angela Carter’s story The Bloody Chamber echoing in my mind. If you’ve never read The Bloody Chamber: And Other Stories , I can’t urge you enough to find a copy as fast as you can. Her adult re-tellings of fairy tales are dark, often sinister, yet beautiful.

Terri Windling’s excellent essay, Blue Beard and the Bloody Chamber, is also a must read.

There is a long history of Bluebeard-like figures weaving in and out of writers’ works. Margaret Atwood’s short story Bluebeard’s Egg is a somewhat recent example (1986) as well as The Robber Bride (1993).

Prior to that, Eudora Welty wrote The Robber Bridegroom and even Charlotte Bronte’s Mr. Rochester in Jane Eyre can be viewed as a Bluebeard of sorts.

Charles Dickens penned a piece in 1860 called Captain Murderer in which the main character is a descendant of the Bluebeard family.

Bluebeard and his treachery proves to be an endless source of literary exploration.

In 1901, cinematic pioneer Georges Méliès produced, directed and starred in Barbe-bleue, a silent film in which he portrayed Bluebeard. The film can be seen in its entirety at Archive.org. As recently as 1993, Jane Campion reinterpreted the Bluebeard tale in her film The Piano.

Bluebeard performs an important role symbolically. He’s in the roots of every story where the villain has dark secrets to hide from their loved ones and is a permanent part of our culture, however well he may be obscured.

Once he has a foothold in your life, he shatters your sense of safety with cruelty and manipulation. No longer a tale for children, Bluebeard represents our worst nightmare: that the one we love and share our life with is truly unknown to us.

So what’s the deal with Margaret “Peggy” Atwood and the Pre-Raphaelites? Cat’s Eye in Draco sees all?