As a little girl, I enjoyed Nancy Drew, Wonder Woman, and Princess Leia, all of whom had moments of peril where they were helped by men, but more often than not relied on their own intelligence and courage to navigate situations and save the day. Yet I also enjoyed adventures of knights and maidens that could be seen by many people as examples of sexist tropes that worn out their welcome.

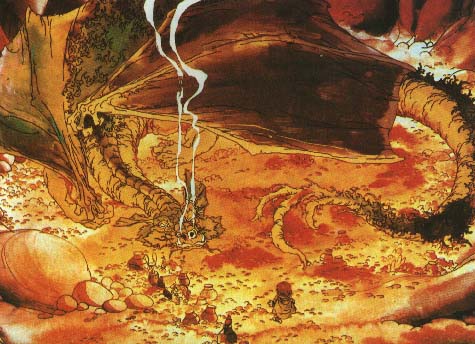

When we see images of knights, maidens, and dragons, it is easy to dismiss them as archaic images of a man rescuing the helpless, weaker sex.

Thinking about this sort of tale, I realize the danger lies not in the story itself, but in treating it as if it is the only story. It becomes a dangerous cliche, a pattern that seeps into the collective consciousness and teaches both males and females that women can’t be the heroines of our own tales.

In poring over Victorian paintings of dragons and damsels, I want to challenge my perceptions of the images and see what, if anything, I can reinterpret and apply to my own experiences. Dragons are a profound metaphor, and metaphors help me process life.

Dragon imagery takes on a deeper meaning if we look at the creature as something to conquer within ourselves. In Joseph Campbell’s The Power of Myth, his notion of the dragon as ego is an apt one that resonates with me.

“MOYERS: How do I slay the dragon in me? What’s the journey each of us has to make, what you call “the soul’s high adventure”?

CAMPBELL: My general formula for my students his “Follow your bliss.” Find where it is, and don’t be afraid to follow it.”

MOYERS: Is it my work or my life?

CAMPBELL: If the work that you’re doing is the work you chose because you enjoy it, that’s it. But if you think, “Oh, no! I couldn’t do that!” That’s the dragon locking you in. “No, no, I couldn’t be a writer,” or “No, no, I couldn’t possibly do what So-and-so is doing.”

MOYERS: In this sense, unlike heroes such as Prometheus or Jesus, we’re not going on our journey to save the world but to save ourselves.

CAMPBELL: But in doing that, you save the world. The influence of a vital person vitalizes, there’s no doubt about it. The world without spirit is a wasteland. People have the notion of saving the world by shifting things around, changing the rules, and so’s on top and so forth. No, no! Any world is a valid world if it’s alive. The thing to do is bring life to it, and the only way to do that is to find your own case where the life is and become alive yourself.

MOYERS: When I take that journey and go down there and slay those dragons, do I have to go alone?

CAMPBELL: If you have someone who can help you, that’s fine, too. But, ultimately, the last deed has to be done by oneself. Psychologically, the dragon is one’s own binding of oneself to one’s ego. We’re captured in our own dragon cage. The problem of the psychiatrist is ti disintegrate that dragon, break him up, so that you may expand to a larger field of relationships. The ultimate dragon is within you, it is your ego clamping you down.

Also, dragons are greedy creatures, obsessing over and hoarding gold they have no actual use for. Their faults, such as viciousness and avarice, are quite human characteristics – abhorrent aspects of ourselves.

My first vivid memory of a dragon was from The Hobbit, specifically the Rankin-Bass animated version of Tolkien’s classic. I watched it several times in my childhood and my brother and I owned the book/cassette version, which I listened to repeatedly. This is no damsel-in-distress tale, it’s the tale of a reluctant adventurer whose ability to survive a perilous journey surprises even himself.

Smaug and Bilbo’s exchanges delighted me because they spoke in riddles, warily challenging each other. Beneath their mutual mistrust, there seemed to be an undercurrent of respect.

Smaug was a beautiful dragon to me, frightening in his jeweled, orange-gold magnificence. He was fiery and fierce, and too arrogant to realize he had a weak spot that would prove to be his downfall.

Without a dragon to outwit, Bilbo may have lived the entirety of his life safely ensconced in his hobbit-hole. A good life, to be sure, but a life in which he would never have learned that he was capable of a grand adventure.

Perhaps we have dragons within us to conquer but, like Bilbo, this just might lead us to greater deeds than we could have ever imagined. Dragons can be scary, but every little victory brings us one step closer to our best selves.

The challenge of the dragon is the challenge of the self, causing us to explore parts of our souls that we rarely encounter, unless visited by catastrophe.

I should not disparage dragons completely, though. My son Donovan, who turns twenty-one today, had a passion for them as a boy. I can still conjure up the magical memory of him at age five, squeezing his eyes shut and desperately wishing that a dragon would come live with him. (A blue and green dragon with iridescent scales, to be exact.)

A dragon like that, in the mind of a child, is filled with hope, promise, and magic. A boy who wishes for a dragon companion could never slay the dragon; he desires to nurture and love the dragon.

Perhaps that is the true lesson. Don’t kill the dragon; endeavor to understand it.