Warning: This post contains spoilers. If you have not seen Vertigo, you might want to back away slowly because I do not want to ruin your experience You have been warned.

“Do you believe that someone out of the past, someone dead, can enter and take possession of a living being?”–Gavin Elster to Scottie in Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo

Vertigo is, in my opinion, one of Hitchcock’s best films. On the surface it begins as a thriller, but it transitions into an exploration of loss, grief, and obsession. Watch it as one who is interested in Hitchcock in a cursory way and it is simply a very good film. Watch it as an obsessive Hitchcock fan and it becomes something deeper. A glimpse into his psyche? A manifesto? It is a study in obsession and creation and lies. It misleads and delights us simultaneously. Whatever it is, I am drawn to it for the same reason I am obsessed with Pre-Raphaelite art. There are layers and complexities here, nuances to tease out and ponder.

Pre-Raphaelite works depend on their vibrant use of color, it’s one of the things that sets them apart from the formulaic Royal Academy approach that inspired the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood to rebel in the first place. While the earliest Pre-Raphaelite works are exquisite examples of jewel-like tones, it is often Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s use of the color green in his later works that I think of when I ponder my love of Pre-Raphaelite color.

As the title sequence in Vertigo unfolds, it sends a message that color is important in this film. We see a passive yet beautiful face, similar to the many images of Pre-Raphaelite women who appear lost in contemplation. The sequence focuses on her features, which summon Pre-Raphaelite comparisons to my mind. Rossetti lips. Burne-Jones eyes. The screen changes color repeatedly and it is a little off-putting. These are not soothing colors, but garish ones. Instead of lulling us into the movie-watching experience, the colors are jarring and a bit uncomfortable. We are then inundated with psychedelic spirals. On the one hand, they may represent the dizzying experience of vertigo, but they are also symbolic of the fact that we are about to be pulled into this vortex of a story as much as Scottie (Jimmy Stewart) is.

Once you start paying attention to color in the film, you notice patterns. Yellow, green, and red appear everywhere. Let’s start with Midge, Scottie’s longtime friend. Played by Barbara Bel Geddes, she is the epitome of the girl-next-door. Quick-witted and funny, she covers her longing for Scottie with a breezy manner. Yet the moment he casually, and one could say cruelly, asks her if they were once engaged, we see a stiffening. “Aren’t you ever gonna get married?” Scottie asks her. ” We were engaged once, weren’t we?” Midge looks up, ever so slightly. Is she wondering how he could have ever forgotten such a thing? There’s something deep to Midge that the confines of the story never lets us fully explore. As we get deeper into the narrative we know she is safe for Scottie. She would never have caused the pain that he experienced due to his obsession with Madeleine. Perhaps it is this reason that Hitchcock chose to introduce her to us with sunny, friendly yellow. She not only wears yellow, but her apartment is yellow. The step stool she hands Scottie is yellow.

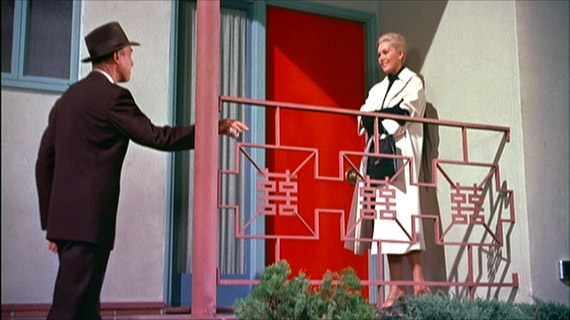

Scottie is associated with red; it often surrounds him on screen, in his furniture and clothes, and even the door of his apartment.

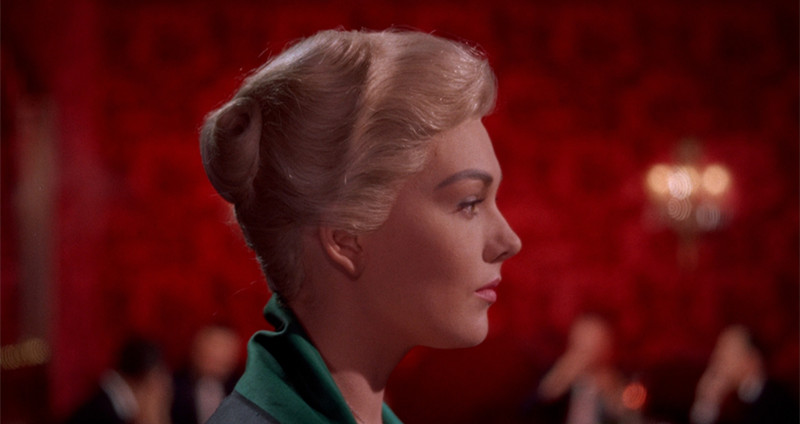

When we first see Madeleine, she is swathed in green just as beautifully as a Rossetti muse. Scottie came to the restaurant only as a favor to his old acquaintance Gavin Elster, who has asked Scottie to follow his wife. He’s concerned that she seems haunted. She loses time, wanders to strange places and goes into trance-like states. Scottie’s uninterested, at this point he’s just going through the motions.

Until he sees her.

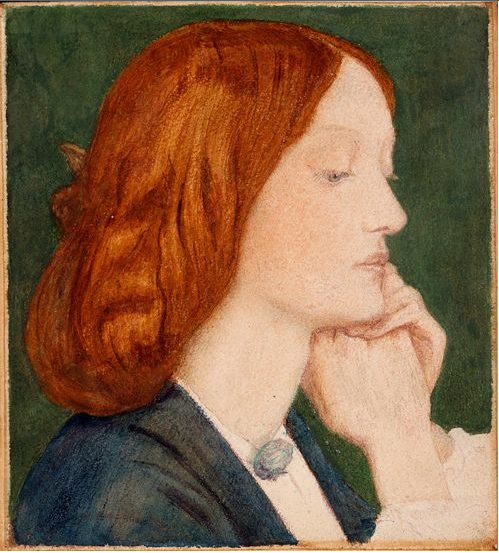

Hitchcock reveals her to us from Scottie’s point of view – Madeleine, wrapped in striking green, leans elegantly and dramatically on the table. She silently crosses the room and we see her in profile, a study in emerald contrasted with the crimson walls. Dante Gabriel Rossetti and his muse Elizabeth Siddal come to mind. In a letter to artist Ford Madox Brown, Rossetti confided that when he first saw Siddal, he felt “his destiny was defined”. The same with Scottie. Madeleine’s beauty, her movement, her profile have all begun to draw him in, and there is no going back.

The following day, Scottie starts to follow her per her husband’s request. As we watch her lead him from place to place, it is obvious that he is intrigued. He never hears her thoughts or her voice, but he is captivated. He’s infatuated with her image. Madeleine is a silent muse, an object of Scottie’s male gaze. She’s still the green-girl, surrounded by verdant Rossetti-like hues. We see it in her car and in the lighting of several scenes.

As he follows her to a cemetery, there is something melancholy and mysterious about Madeleine. There is a sadness to her that is somehow beautiful, untouchable. At this point, Scottie possibly feels a mixture of curiosity and chivalry. He wants to understand her as well as save her.

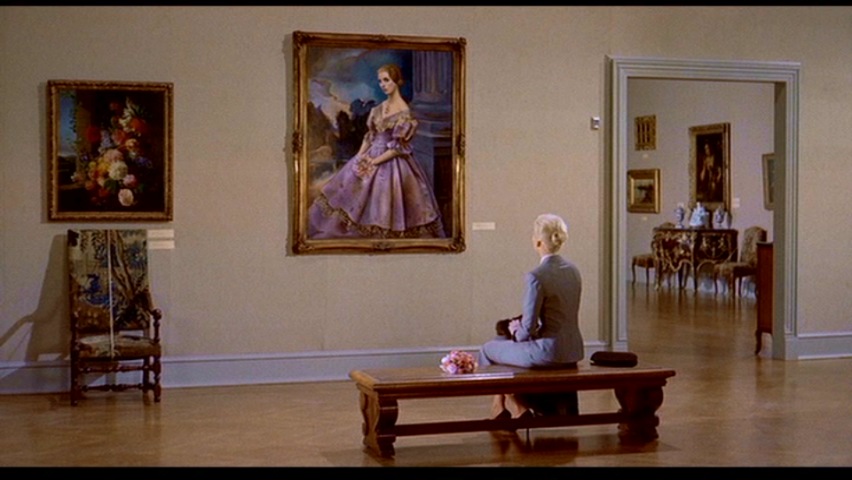

He follows Madeleine to a museum. We don’t really see her face in this scene. It is all about him, his gaze, and his interpretation of her and the painting.

At this point in the film, we don’t know that everything is a lie. We don’t need to see her face because what she feels about the painting isn’t genuine. She’s merely playing a part, with Gavin Elster as the artist in the background constructing a tableau. Once you watch Vertigo for the second time and understand the machinations involved, the museum scene takes on new significance. We follow Scottie’s eyes, we see the mental connections he makes as he is pulled further into the deception. The connections aren’t real, they are artfully planned.

Madeleine’s carefully pinned hair is just as important as the loose, wild tresses in Pre-Raphaelite imagery are. Her hair conveys a message; it displays her connection and obsession to the mysterious and long-dead Carlotta.

The jewelry Carlotta wears in the painting is important as well. It will resurface later, but apart from its usefulness as a plot device, the jewelry in her portrait reminds me of Rossetti’s repeated use of jewelry in several of his works. The necklace in Fair Rosamund and Bocca Baciata, for example. Or his repeated use of the spiral hair pin.

Earlier, Madeleine has purchased a sweet little bouquet of flowers. Interestingly, she did not leave the flowers at Carlotta’s grave. When we see the flowers in the portrait, it can be assumed that the flowers didn’t need to be placed on the grave because Madeleine herself is Carlotta.

Scottie turns to Midge to fill in the gaps of Carlotta’s story. When she introduces him to bookshop owner Pop Leibel, Scottie is told the sad tale of Carlotta, who went mad when her child was taken away by her lover. Carlotta committed suicide and apparently she is reaching across the branches of her family tree and possessing the unsuspecting Madeleine, her great-granddaughter. Carlotta is mad with grief, like a Pre-Raphaelite Ophelia.

Madeleine’s bouquet presents an interesting parallel to Ophelia, Hamlet’s tortured ingenue. Depicted repeatedly by Pre-Raphaelite artists, Ophelia’s sad tale is filled with flowers, water, and death. When a trance-like Madeleine visits Fort Point, she tears up the bouquet and sprinkles the remnants into the bay. The flowers float there, a visual reminder of Ophelia’s flowers floating along with her in her watery grave, her clothes ‘spread wide and mermaid-like’. Madeleine jumps into the bay in an apparent suicide attempt, making the Ophelia parallel complete.

Scottie carries her, wet and dripping, to his car. She is a rescued Ophelia, a Lady of Shalott saved from that whispered curse. The knight has, according to his code of chivalry, rescued her from drowning.

Scottie brings her to his apartment and in this scene, they speak to each other for the first time. Notice that their colors are now swapped, Madeleine is in red while he is in green.

“Their true name is Sequoia sempervirens — always green, everliving,” Scottie says of the trees when they visit Big Basin. “What are you thinking?” he asks. Madeleine answers, “Of all the people who’ve been born and who died while trees went on living. I don’t like it, knowing that I have to die.” Madeleine traces the rings of a felled tree. “Somewhere in here I was born…and there I died. It was only a moment for you, you took no notice.”

When Madeleine invokes these things, she is crafting a spell and Scottie is falling further and further into her magic. She is more than an actress here as she leans against the massive trunk. She is a dryad among the trees, inviting and pulling him into madness that he does not yet understand.

The pair visit mission San Juan Bautista together. It is here that Madeleine runs up into the bell tower and plunges to her death while a helpless Scottie is unable to save her due to his fear of heights and vertigo. Her death devastates him, and suffering from what a doctor describes as acute melancholia and guilt, he spends time in a hospital to recover from the loss.

Later, he becomes obsessed with the memory of Madeleine and constantly retraces their steps. He sees blondes everywhere and from a distance they resemble her, but upon closer examination the truth is delivered swiftly to him that she is gone, irreversibly gone.

Or is she? Outside a flower shop he sees Judy Barton, as unlike Madeleine in demeanor and class as she could be, save for her beautiful face. The vivacious redhead’s demeanor is a stunning contrast to Madeleine’s cool blonde comportment, yet her facial features are the same. The first time we see Judy, she is clothed in green. Brighter green than Madeleine, but green just the same.

Then the truth is revealed to us – Scottie never met the true Madeleine, and Judy was playing her part all along. Yet Judy loves Scottie and decides to go on pretending in the hopes that he might love her too. Like an artist who can’t see his muse for who she really is, but only for what he can mold her into, Scottie is focused on Judy solely for the possibilities she embodies. He can use her to resurrect the woman he believes he lost; a woman who never existed. As Christina Rossetti said in her poem In An Artist’s Studio, “Not as she is, but as she fills his dream.”

In An Artist’s Studio, Christina Rossetti

One face looks out from all his canvasses,

One selfsame figure sits or walks or leans;

We found her hidden just behind those screens,

That mirror gave back all her loveliness.

A queen in opal or in ruby dress,

A nameless girl in freshest summer greens,

A saint, an angel;—?every canvass means

The same one meaning, neither more nor less.

He feeds upon her face by day and night,

And she with true kind eyes looks back on him

Fair as the moon and joyful as the light;

Not wan with waiting, not with sorrow dim;

Not as she is, but was when hope shone bright;

Not as she is, but as she fills his dream.

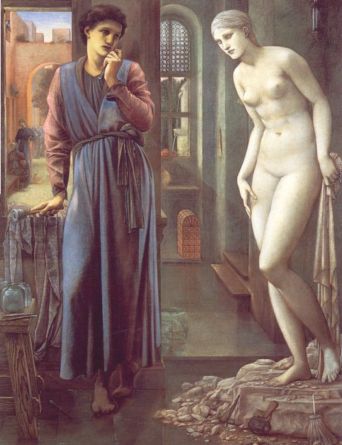

Scottie, in his attempt to recreate Madeleine, becomes a Pygmalion figure. The sculptor, dissatisfied with local women, created a statue so perfect and lovely that he prayed to Aphrodite to give him a wife as perfect as his creation. Aphrodite heard his prayers and brought his statue to life. The tale dates back to Ovid’s Metamorphoses and inspired George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion, which in turn was the basis for the musical My Fair Lady.

Vertigo is perhaps a darker exploration of this Pygmalion-esque obsession. Yet if Scottie is Pygmalion, then perhaps Hitchcock is too. In film after film, he crafted and molded the “Hitchcock blonde” so intensely and frequently that now we associate her sleek, sophisticated coolness with his work as much as we associate Elizabeth Siddal and Jane Morris with the works of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Women are central figures in both Hitchcock’s and Rossetti’s work. Paint the women out and there isn’t much left to explore.

When Scottie discovers the truth, he takes Madeleine/Judy back to the scene of the crime. In a frenzied scene, Hitchcock orchestrates a suspenseful trek up the staircase as Scottie confronts Judy. Ironically, once he realizes he has conquered his vertigo, Judy is startled by a nun entering the tower.

Judy falls to her death, the third plunging fatality to torment Scottie.

We’ve reached the end, but it never feels like the end for me. Like a painting, the imagery and the narrative linger in my head. There’s so much to think about with Vertigo that I experience it in a backward fashion, starting with Judy’s death and following the thread of everything that led before.

What is this film, exactly? It’s a doppelganger tale. It’s an exploration of fetishism and obsession. And it’s a good old-fashioned murder story. There are layers and symbolism to unpack and explore. The tragedy of it haunts me as much as any Ophelia painting. Hitchcock created a film that speaks to us in the same way as a Rossetti masterpiece. “I don’t want to die. There’s someone within me and she says I must die,” Madeleine cries to Scottie as he embraces her.

This is pure Pre-Raphaelite melodrama to me and I love each and every second.

Great post! I enjoyed it so much! Xx Robin

Thank you!

It’s such a kick experiencing life vicariously through your Pre-Raphaelite eyes!

I commented over on IG, but I loved this article. I love Vertigo and had made the same observations about color and spirals, but I’d never connected it to the Pre-Raphaelite’s. I think Rossetti’s “How The Met Themselves” could be included here. That meeting of our doppelgängers is a precursor to death.

Simply superb in all aspects

JD

Thank you!

Really interesting and unusual take on Vertigo!!

Thank you! Glad you enjoyed it!

Thank you for this! So informative.

Loved this! I was struck by the scene when Scottie sees Madeleine for the first time; I thought, “This scene is familiar.” It’s just like a Sherlock Holmes film when Sherlock sees the woman he must follow for the first time. She is in an elegant restaurant with a man. The film (though black & white) is “The Woman in Green.”