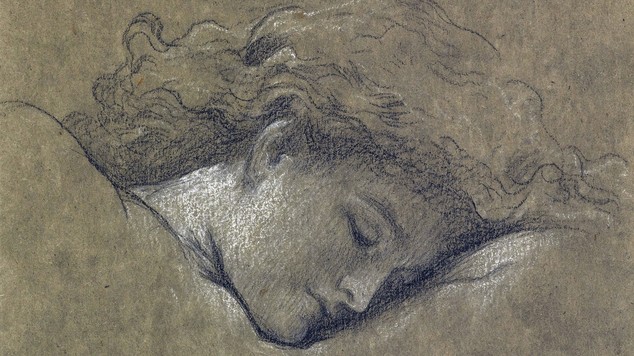

Recently, an unknown study for Leighton’s Flaming June was discovered. The discovery was almost cinematic: Pre-Raphaelite study discovered behind door in English mansion. After the discovery, the sketch sold for a whopping £135,000 through Sotheby’s.

I have a rather large framed print of Flaming June in my bedroom, so it is an image I see daily, although I am aware that the print pales in comparison to the original which is currently on display in New York.

I’ve mentioned my love of artistic studies on this site before. I feel they give a deeper glimpse into the artistic process, a private view into a world the artist might not have intended us to see. To view them is the sharing of a secret. Often I find that studies capture a depth of emotion and the models’ faces hold entire stories untold. Studies are raw and uninhibited. When I heard of the study for Flaming June, I could not stop myself from staring at her face repeatedly and searching, perhaps, for meaning.

That iconic orange gown, the flowing hair. Those are the things we usually focus on in the finished painting. It’s a gorgeous work. In the study, however, we see only her slumbering face.

I’ve blogged about slumber before. So I have decided to dip into the archives and share that post again now, in honor of Leighton’s study resurfacing.

The Art of Slumber

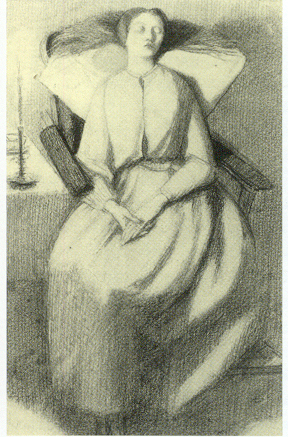

The Sleeping Model by William Powell Frith is a work that I find incredibly interesting. The tedious act of sitting for the artist has caused the model to fall asleep. Undeterred by her slumber, he paints her face as if she is awake. The mannequin sprawled in the corner behind her seems curiously alert. It’s an odd juxtaposition, the inanimate object ‘awake’ while the living model sleeps.

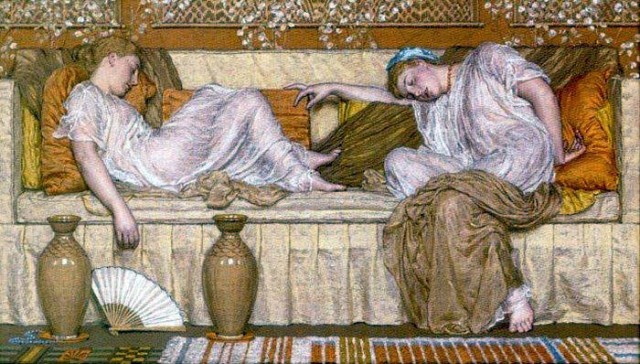

You would think that the image of someone sleeping would be a boring one. Yet images like Leighton’s Flaming June remain extremely popular. I myself have a print of Flaming June in my bedroom and an oil copy of Albert Moore’s A Sofa in my living room. Why are images of sleep so compelling?

Is it voyeuristic? We the viewers are intruding upon a woman at her most vulnerable. Especially in the case of E. Corbett’s The Sleeping Girl (above). Sleeping and partially exposed, she seems unaware that she is being watched. Or perhaps I am wrong and voyeurism is not a factor, perhaps it is simply using beauty and sleep as an illustration for that perfect dream state we all long to reach every night. That magical time where we can enter a different world, a pleasant dream where we can do and be anything. A good sleep is healing; sleep rejuvenates. And if you sleep attired in a gauzy gown arranged just so, someone may paint your picture.

The Briar Rose presents a different example. Presented within a narrative, her slumber exists in the magical world of a fairy tale. This is the sleep of enchantment, a sort of magical stasis. Burne-Jones presents the story of The Sleeping Beauty in a series of four paintings with ten adjoining panels, the fourth and final painting shown here:

The artist’s daughter Margaret posed as the sleeping princess. In the recent anthology Queen Victoria’s Book of Spells edited by Terri Windling and Ellen Datlow, Elizabeth Wein’s story ‘For the Briar Rose’ explores Margaret’s experience posing for her father. It is a lovely story and an excerpt is included in Grace Nuth’s post at The Beautiful Necessity.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti drew and painted his muses obsessively. First Elizabeth Siddal and, in later years, Jane Morris. At times he depicted both of them at rest. Both had physical complaints so it is possible that images of them resting may have something to do with discomfort.

Later he depicted Fanny Cornforth asleep in Bottles. I confess that this painting has been a source of confusion for me. I long believed it to be of Elizabeth Siddal, but now believe it is Fanny. Fanny also believed it to be of her.

Sleep has also been viewed as relative to death. I think we have a need to believe they are similar states of conciousness. We hope that death will be restful, hence our notion of Resquiat in Pace ( Rest in Peace).

Waterhouse’s Sleep and his Half-Brother Death may have been inspired by the death of the artist’s two brothers from tuberculosis.

Burne-Jones presents the death of King Arthur in The Last Sleep of Arthur in Avalon. Surrounded by attendants, Arthur’s death is likened to peace and sleep. In Georgiana Burne-Jones’ Memorials of Edward Burne-Jones, she quotes her husband as saying “The Sleep of Arthur in Avalon is my chief dream now, and I think I can put into it all I most care for.” He later said “I have no politics, and no party, and no particular hope: only this is true, that beauty is very beautiful, and softens, and comforts, and inspires, and rouses, and lifts up, and never fails.” Perphaps this is why death is often seen artistically as sleep. To soften the loss and comfort those of us left behind. As Shakespeare wondered in Hamlet, for in that sleep of death what dreams may come?

Also see Kirsty Stonell Walker’s post Bejewel my hair with coins as I sleep