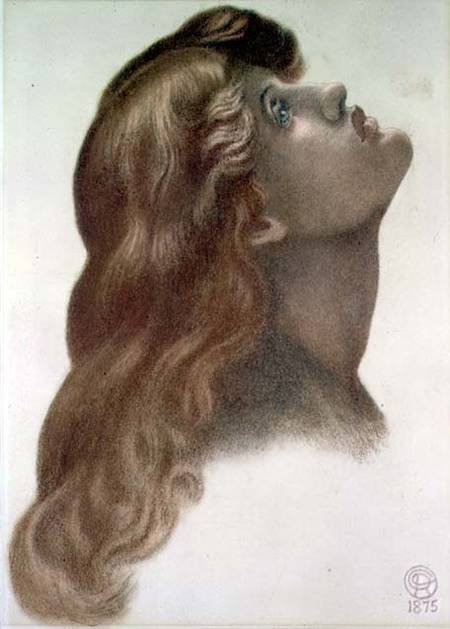

coloured chalks on paper

50×35.5

© Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford, UK

English, out of copyright

As far as Rossetti’s painting goes, I felt an actual physical reaction to the work when I saw it in person. I had seen it reproduced in books many times, but in print form, it was his Proserpine or his many images of Elizabeth Siddal that captivated me. In person, though, Astarte Syriaca had command of the room. She drew me to her fiercely as if this painted image of Jane Morris truly was imbued with some sort of mesmerizing power. It is a painting you find hard to walk away from. Ever since that moment, this has been an image that inspires me. One that I turn to again and again.

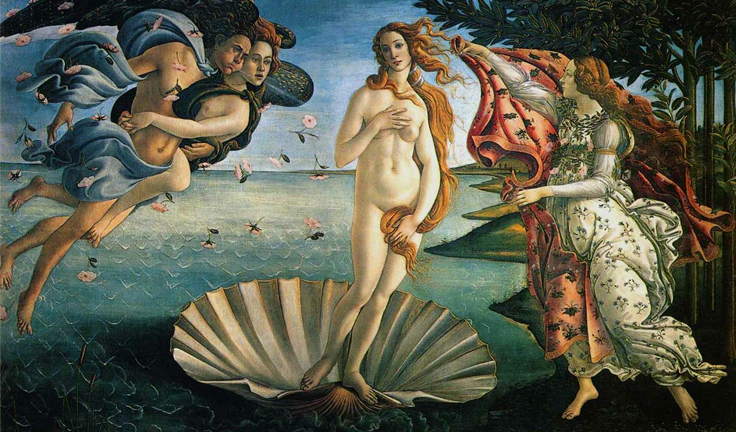

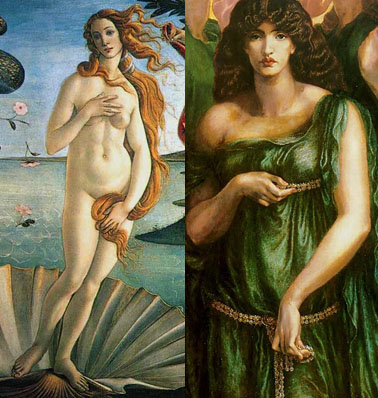

While Botticelli’s Venus is a full-frontal nude that sways lightly to the side with her head delicately tilted, Rossetti’s primordial goddess faces us head on. This is an unwavering being. She’s powerful and direct without any of the tenderness we see in Botticelli’s work. Rossetti’s goddess is no ingenue. She reigns supreme.

While Botticelli’s Venus is a full-frontal nude that sways lightly to the side with her head delicately tilted, Rossetti’s primordial goddess faces us head on. This is an unwavering being. She’s powerful and direct without any of the tenderness we see in Botticelli’s work. Rossetti’s goddess is no ingenue. She reigns supreme.

This pose, known as a ‘pudica pose’, isn’t limited to the works of Botticelli. He had certainly studied the Venus de Medici and the pose can be found in several examples of classical art.

When Rossetti used the pudica pose in Astarte Syriaca, it seems to me that he transformed it from a pose of fragile feminity to a stance of strength. Historically, the strength conveyed here was not the type of woman that girls were encouraged to emulate. Generations of women were (many still are) raised on a steady diet of damsel-in-distress tales. Long before the Barbie doll was a career gal, her existence was limited to a beauty of unattainable physical proportions and sparkly clothes. Before Brave gave us Merida, most animated movies gave us stories where the princess is never the adventurer. Merida shows girls that we can be both. Rossetti may have been attempting to tap into a darker, more primal version of a goddess, but in doing so I think he was unintentionally ahead of his time. In Astarte Syriaca he created a goddess that transcends traditional stereotypes. He gave us an example of primal feminine strength.

Pre-Raphaelite artists are responsible for giving us innumerable images of beautiful women. This is not without its detractors. Often described as languid or lifeless, many have dismissed Pre-Raphaelite representations of women as created solely for the male gaze. I champion the idea that at times, we can reclaim and reinterpret these works. As women, our enjoyment certainly carries weight as well, no matter what the original intent. We can and should draw inspiration from Pre-Raphaelite art if that’s how we feel about them. Astarte Syriaca, for me, is one such source of inspiration.

I have said that the goddess in Astarte Syriaca draws upon a beauty that is more powerful than delicate. Does this mean that I eschew the traditional ideas of feminine beauty? Not in the least. There are many aspects to our feminine nature and we should explore them all. Women are complex beings. The problem with stereotypes is that they fail to present a full picture and if we fall for them, we limit ourselves and miss a richer and deeper experience. Instead of choosing between damsel-in-distress mode or warrior mode, perhaps we should recognize that throughout our lives we have probably been both. Sometimes we need saving. Sometimes we are the savior.

Astarte Syriaca, Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Mystery: lo! betwixt the sun and moon

Astarte of the Syrians: Venus Queen

Ere Aphrodite was. In silver sheen

Her twofold girdle clasps the infinite boon

Of bliss whereof the heaven and earth commune:

And from her neck’s inclining flower-stem lean

Love-freighted lips and absolute eyes that wean

The pulse of hearts to the spheres’ dominant tune.

Torch-bearing, her sweet ministers compel

All thrones of light beyond the sky and sea

The witnesses of Beauty’s face to be:

That face, of Love’s all-penetrative spell

Amulet, talisman, and oracle, —

Betwixt the sun and moon a mystery.

There is a marriage of beauty and power in this painting which I think you have drawn out perfectly in this post. I have always wondered about the two figures in the background. Are they supposed to act as a contrast to the main figure, perhaps representing more traditional views of femininity? Interesting that one of them is based on Jane Morris’s daughter (the figure in the painting looks older than 13 which I think is how old she would have been)