The hills grow darker to my sight

And thoughts begin to swim. (from Elizabeth Siddal’s poem At Last)

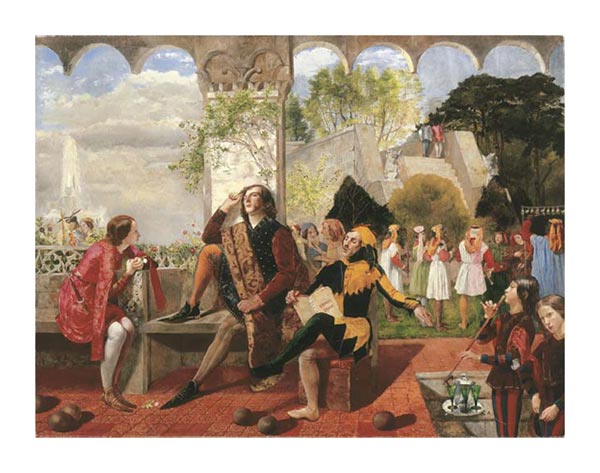

Lizzie was discovered in millinery shop, a simple girl who was tall for the time and had a mass of red-gold hair. Her first sitting was for Walter Deverell’s Twelfth Night.

On this day in 1829, Elizabeth Eleanor Siddall was born (she dropped a letter L from her name when she became an artist). I write about her frequently on this site; she’s a woman I admire immensely. You can visit my other site, LizzieSiddal.com to see a timeline of her life, view her paintings, and read her poems. One of my favorites is her powerful yet bitter poem Love and Hate.

She wasn’t famous in her own lifetime. Although she did sell a few pieces of art and secured the patronage of critic John Ruskin, she was unable to meet her full potential. Her poems were never published while she was alive. As a result, she is overshadowed both by the ghostly legend that surrounds her and by the reputation of her husband. What we know about her is only in relation to him. The picture is not a full one and the gaps only add to her mystery.

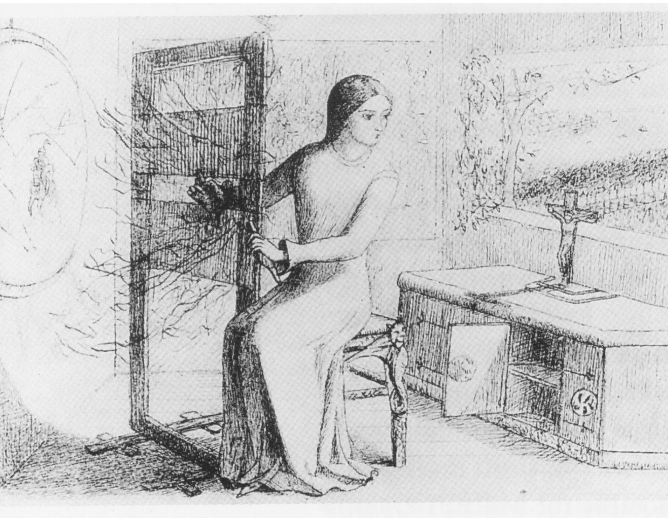

She didn’t produce a large body of work and what survives shows a raw, unfinished talent. Her paintings and drawing are simple in execution and, at times, they show a distinct Medieval influence. As an artist, she is often dismissed and her work is assumed to be heavily influenced by her mentor and husband Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Is this completely fair, though? To be sure, they probably influenced each other a great deal. As her tutor, Rossetti helped shape her artistic eye. Yet it doesn’t escape my notice that with women artists, people can be quick to assume that their work was largely helped by some man in their life. When I see an image by, say, Joanna Boyce Wells posted on Facebook, I always see a comment asking “how much did her brother have to do with this?” Yet when work is posted by a male artist, no one seems to question that the work is not solely his own.

The Pre-Raphaelites are known for several depictions of the Lady of Shalott. Did you know that one of the earliest Pre-Raphaelite depictions of the Lady of Shalott was a drawing by Elizabeth Siddal?

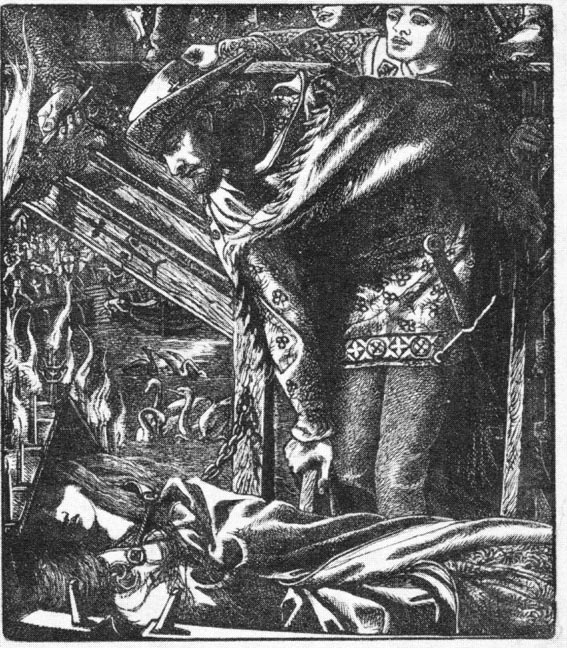

We can see her facial features in Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s 1857 drawing for Edward Moxon’s illustrated collection of Tennyson’s poems, making Siddal an artist who both created her own Lady of Shalott as well as appearing as the Lady of Shalott at a later date.

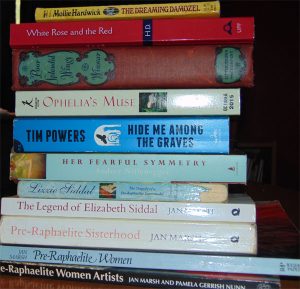

The story of Elizabeth Siddal is a compelling and sad one that lends itself well to fiction. In 1990 Mollie Hardwick, creator of Upstairs Downstairs, wrote The Dreaming Damozel, a mystery that has main character Doran Fairweather, an antique dealer, drawn deeper and deeper into an obsession with both Rossetti and Siddal. Fiona Mountain inventively used Siddal’s life as the catalyst for a modern day mystery in her 2002 book Pale as the Dead, featuring her protagonist Natasha Blake as a detective with a twist. She’s a genealogist who can solve both the mysteries of your ancestors and any crime that crosses her path (I highly recommend both Pale as the Dead and the sequel Bloodline). Audrey Niffenegger gave Siddal a brief cameo appearance in Her Fearful Symmetry, a tale that revolves around Highgate Cemetery, Siddal’s final resting place. Siddal and the entire Rossetti clan get the vampire treatment in Tim Powers’ book Hide Me Among the Graves. Author Rita Cameron wrote Ophelia’s Muse, a novelized version of the relationship between Siddal and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Most recently, Kate Forsyth explored Siddal and the Pre-Raphaelite circle in Beauty in Thorns.

The story of Elizabeth Siddal is a compelling and sad one that lends itself well to fiction. In 1990 Mollie Hardwick, creator of Upstairs Downstairs, wrote The Dreaming Damozel, a mystery that has main character Doran Fairweather, an antique dealer, drawn deeper and deeper into an obsession with both Rossetti and Siddal. Fiona Mountain inventively used Siddal’s life as the catalyst for a modern day mystery in her 2002 book Pale as the Dead, featuring her protagonist Natasha Blake as a detective with a twist. She’s a genealogist who can solve both the mysteries of your ancestors and any crime that crosses her path (I highly recommend both Pale as the Dead and the sequel Bloodline). Audrey Niffenegger gave Siddal a brief cameo appearance in Her Fearful Symmetry, a tale that revolves around Highgate Cemetery, Siddal’s final resting place. Siddal and the entire Rossetti clan get the vampire treatment in Tim Powers’ book Hide Me Among the Graves. Author Rita Cameron wrote Ophelia’s Muse, a novelized version of the relationship between Siddal and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Most recently, Kate Forsyth explored Siddal and the Pre-Raphaelite circle in Beauty in Thorns.

Siddal has even received the comic book treatment thanks to a particularly well-done comic story by Neil Gaiman, How They Met Themselves. The title is drawn from the Rossetti painting of the same name (pun totally intended). My friend Ben Perkins recently blogged about Gaiman’s comic at The Talking Oak’s Popular Victoriana Compendium.

In 1967, director Ken Russell filmed Dante’s Inferno which featured Oliver Reed as Rossetti and Judith Paris as Siddal. It’s a quirky depiction of the Pre-Raphaelite circle, very sixties and a delight to watch.

Amy Manson portrayed Elizabeth Siddal in Desperate Romantics, a wildly inaccurate romp of a series that has introduced the Pre-Raphaelites to a new audience. There were many liberties taken in this production that I can not approve of, but I will say that Manson portrays Siddal with strength and spirit. And visually, the scenes of Siddal as Millais’ Ophelia are stunning. While I have several friends that love it, I admit that I can’t help but cringe while watching it. Perhaps I am too much of a purist. You’ll have to watch it and decide for yourself.

In the theater world, playwright Jeremy Green brought Siddal to the stage in Lizzie Siddal (2013). Author Dinah Roe has a great interview with Jeremy Green about his work on her site Pre-Raphaelites in the City. And I’m proud to be friends with not one but two talented actresses who staged their own productions telling Siddal’s story: Kris Lundberg brought Siddal to life in Muse. Valerie Meachum staged Unvarnished, a one-woman show.

Fiction, movies, plays…Siddal may not have achieved recognition in her own lifetime, but she certainly has our attention now. As Rossetti’s muse, we can see her influence on his early Pre-Raphaelite works. She then boldly made the move from a muse to artist and embarked on a career that was sadly short but showed great promise. Unfortunately, many of the sad details of her life overshadow her artistic ambitions. Even so, I still think she inspires women and has become a symbol that can motivate us; she represents a woman strong enough to create her own work in a rigid, patriarchal world.

In The Legend of Elizabeth Siddal, Jan Marsh said, “in writing about Elizabeth Siddal, women are painting collective self-portraits.” I believe that is unequivocally true. For close to twenty years I have studied her, read about her, pondered her, attempted to excavate some sort of concrete knowledge of who she truly was. In doing so, I have explored myself. Perhaps Elizabeth Siddal has strangely become a conduit through which we explore our own meanings and desires. No matter how much we learn about her and discuss her, she remains unreachable. In that enigmatic state, I think we project our own needs onto her. She becomes a symbol of ourselves, maybe. The part we want to rescue. I’ve often said that when I embrace images of Ophelia, I am reaching into the past and comforting my teenage self. Perhaps when we champion Elizabeth Siddal, we as women are cheerleaders for our own work, our own creative endeavors. Fighting against the people that disappoint us in a way she couldn’t, fighting against addiction in a way she was ill-equipped to do.

Whatever Elizabeth Siddal means to us individually and collectively, today is the anniversary of her birth. On such a day, I see her mentioned widely on social media. I wonder what she would think if she knew of her influence. How would she feel if she knew she has achieved an almost cult following?

Happy Birthday, Elizabeth Eleanor Siddal Rossetti. Thank you. Requiescat in pace

You may also enjoy these posts:

Did Elizabeth Siddal inspire Bram Stoker’s Dracula?

Regina Cordium (Queen of Hearts)

The Worst Man in London (hint: who orchestrated Lizzie Siddal’s exhumation?)

What is the Pre-Raphaelite Woman?

Elizabeth Siddal: Laying the Ghost to Rest

What shapes our perception of Elizabeth Siddal?

Elizabeth Siddal and Sylvia Plath are not your Suicide Girls