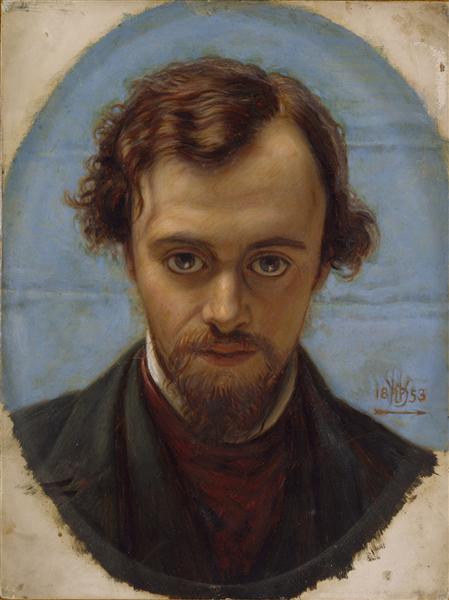

While re-reading Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Family Letters, edited by his brother William Michael Rossetti, I was struck by this passage about DGR’s reading habits.

First of all, I love William Michael’s descriptors. Saying Rossetti ‘drunk deep of an author’ and ‘surged through its pages like a flame’ presents a reading life that mirrors the way I feel about my own, a passionate and consuming drive, a journey that never ends.

I thought using the passage to create a Rossetti reading list would be a fun pursuit. I’ve read many of them, definitely not all, but to read as a way to explore Rossetti further seems a worthy endeavor. You may remember the reading list I created from William Allingham’s diaries. Here’s how WMR described his brother’s reading.

***

“Rossetti’s taste for reading, in all the days of his youth, was never stationary; it continued shifting and developing. After having drunk deep of one author, he went on to another. In 1844 someone told him that there was another poet of the Byronic epoch, Shelley, even great than Byron. He brought a small pirated Shelley, and surged through its pages like a flame. I do not think that he ever afterwards read much of Byron; although as much as his mind matured, he was not inclined to allow that the poet of such an actuality as Don Juan could be deemed inferior to the poet of such a vision as Prometheus Unbound. (Not indeed that he approved of Don Juan, as regards the spirit in which it is written. Early in 1880 he went so far as to tell me he considered it a truly immoral and harmful book.) Keats followed not long after Shelley, in 1846, or perhaps 1845. My brother considered himself to have been one of the earliest strenuous admirers of Keats, but this can only be correct in a certain sense. The Old British Ballads and Mrs. Browning were read with endless enjoyment; also Alfred du Musset (I have previously mentioned Victor Hugo), Dumas (dramas, and afterwards novels), Tennyson, Edgar Poe, Coleridge, Blake, Sir Henry Taylor’s Philip van Artvelde, Thomas Hood–more especially some of his serious poems, such as Lycus the Centaur and The Haunted House, and the semi-serious Miss Killmansegg and her Precious Leg, though some of his roaring jocularities were also much in favour. As to Dr. Hake’s nebulous but impressive romance, Vates, some details will appear elsewhere. Hoffman’s Contes Fantastiques (in French), and in English Chamisso’s Peter Schlemihl, and Lamotte-Fuque’s Undine and other stories, represented the Teutonic element in romance and legend.”

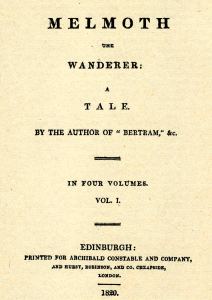

“It may have been towards 1846 that my brother came upon the prose Stories after Nature of Charles Wells, and his poetic drama of Joseph and his Brethren. These works, already half-forgotten at that date, were enormously admired by Rossetti, and the ultimate outcome of his admiration, transfused through the potent faculty and pen of Mr. Swinburne, was the republication of the drama about 1877. Earlier than most of these–beginning, I suppose, in 1844–was the Irish romancist Maturin, who held Dante Rossetti spellbound with the gloomy and thrilling horrors of Melmoth the Wanderer. He and I used often to sit far into the night reading the pages one over the other’s shoulder; and, if to stir the imagination of an imaginative youth is one aim of such a romance as Melmoth, no author can ever have succeeded more manifestly than Maturin with Dante Rossetti. There was another grim romance of his, named Montorio, which we thought a splendid pendent to Melmoth, not to speak of Women, The Wild Irish Boy, and The Albigenses; Maturin’s once celebrated verse-drama of Bertram, and some other poems of his, were eagerly inspected, but without any genuine result to correspond. Two other English novels which he read in these years with keen enjoyment were the Tristram Shandy of Stern, and the Richard Savage of Charles Whitehead; and in French, by Reybaud, Jerome Paturot a la recherche d’une Position Sociale, and, by Eugene Sue, the Mysteres de Paris, the Juif Errant, and Mathilde. In Dickens my brother’s interest may have been on the wane when Dombey and Son began in 1846, though I suppose he read David Copperfield, 1849. In his last days he was much struck with the Tale of Two Cities. To Dickens succeeded Thackeray, who was the most highly appreciated: his early tales in Fraser’s Magazine, such as Fitzboodle’s Confessions and Barry Lyndon, and The Paris Sketchbook (even before Vanity Fair appeared in 1846), also The Book of Snobs. Later on, a novel ascribed to Lady Malet, Violet or the Danseuse, was a great favorite; and he had a positive passion for Meinhold’s wondrous Sidonia the Sorceress (translated), which he much preferred to the Amber Witch of the same phenomenal author.” (See more on Sidonia in this post)

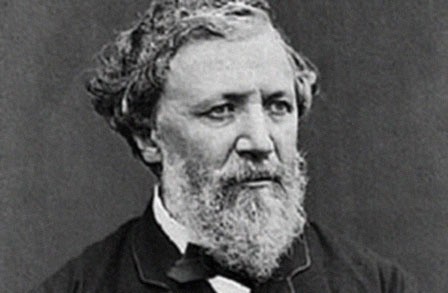

“At last–it may have been in in 1847–everything took a secondary place in comparison to Robert Browning. Paracelsus, Sordello, Pippa Passes, The Blot on the Scutcheon, and the short poems in the Bells and Pomegranates series, were endless delights; endless were the readings, and endless the recitations. Allowing for a labyrinthine passage here and there, Rossetti never seemed to find this poet difficult to understand; he discerned in him plenty of sonorous rhythmical effect, and reveled in what, to some other readers were mere crabbedness. Confronted with Browning, all else seemed pale and in neutral tint. Here was passion, observation, aspiration, and medievalism, the dramatic perception of character, act, and incident. In short, if at this date Rossetti had been accomplished in the art of painting, he would have carried out in that art very much the same range of subject and treatment which he found in Browning’s poetry; and it speaks something for his originality and self-respecting independence that, when it came to verse-writing, he never based himself upon Browning to any appreciable extent, and for the most part pursued a wholly diverse path. It should not be supposed that, in glorifying Browning, Rossetti slighted other poets previously the object of his homage. He valued them at the same rate as before, though he thought Browning a step further in advance. I need scarcely add that Shakespeare and Dante are to be excepted, for at no time would he have denied or contested the superiority of these, even to the poet of Sordello. The time of Dante had come some three years before Browning began, and the current Rossetti’s love for the Florentine flowed wider and deeper month by month.” (Read more about DGR and Dante Alighieri in the posts Shades of Dante and Embracing Dante Alighieri.)

“It may be noted that (as in a previous instance) I have not specified any books of a so-called solid kind–history, biography or voyages. Science and metaphysics were totally out of Rossetti’s ken. I do not believe he read any such books at this period–very few at any later period, among the few Boswell’s Johnson holding a high place. In current talk Rossetti did not appear to be much behind other persons when history or biography was referred to; but I hardly know what historical volumes he opened, other than Carlyle’s French Revolution, Merivale’s Roman Empire, and something of Plutarch and of Gibbon. The great Duke of Marlborough‘s English History came out of Shakespeare’s plays:Rossetti’s English and other history derived largely from the same source, supplemented by those adust chroniclers, Walter Scott, Bulwer, Victor Hugo, and Dumas. This was not to our father’s liking. I have more than once heard him say “When you have read a novel of Walter Scott, what do you know? The fancies of Walter Scott.”