Women are central figures in Pre-Raphaelite art, and this has given rise to the concept of a “Pre-Raphaelite Woman.” I frequently see the term in the media, usually describing an actress or singer with long curly hair. Florence Welch is often described as Pre-Raphaelite, a look she has embraced.

But was there a unified ideal? If we look beyond the canvasses and see the living models who posed for them, we see different types of women. To the credit of the Pre-Raphaelites and their followers, not just one standard was idealized. Women of different shapes and sizes were inspirations, and the strengths of each have merged into what we now recognize as the Pre-Raphaelite Stunner.

While I abhor the act of reducing a woman by referring solely to her physical appearance, let’s look at a few of the models and how their images shaped what we now describe as “Pre-Raphaelite.”

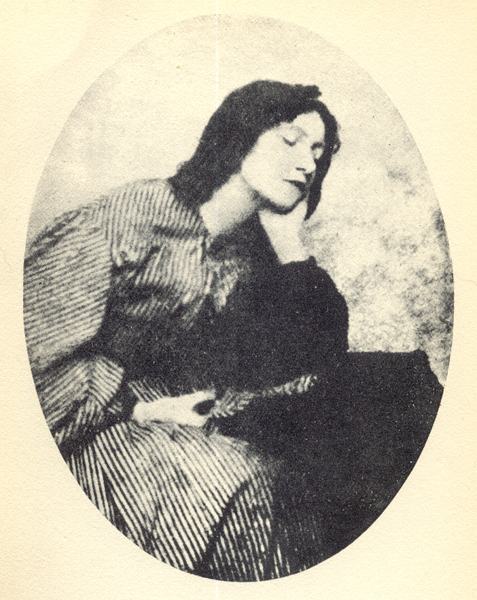

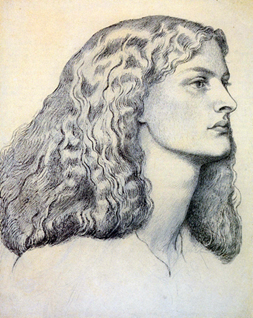

Elizabeth Siddal

One of the earliest models was Elizabeth Siddal. Discovered while working in Mrs. Tozer’s millinery shop, Siddal first appeared in Walter Howell Deverell’s painting Twelfth Night. She went on to model for William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais (as his famous Ophelia). Eventually she posed only for Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Siddal became his pupil and embarked on a promising art career of her own. Their on/off relationship lasted nearly a decade before they finally married in 1860.

Always described as being in ill-health, Siddal was addicted to the opiate Laudanum. A stillborn daughter was the tragedy that sealed her fate and Siddal’s depression sent her further into the depths of addiction, resulting in her overdose death in 1862.

Her passing affected Rossetti for the rest of his life. Seven years later, while struggling with mental health issues, Rossetti had her grave exhumed in order to retrieve the poems he had buried with her. It was a sad, tumultuous time in his life and that one act has forever linked Siddal’s name with a tinge of the macabre.

At the beginning, though, her features inspired Rossetti’s work. In the words of his sister Christina Rossetti’s poem In An Artist’s Studio, “He feeds upon her face by day and night.”

In a similar vein, fellow artist Ford Madox Brown described Rossetti’s repeated and obsessive drawings of Siddal as a “monomania.” In a letter to Madox Brown, Rossetti confided that when he first saw her, he felt “his destiny was defined.” I’m sure he meant on a personal level, but on a professional level it certainly does seem that the destiny of his work was defined when she became his muse. Her features are discernible in most of his drawings and paintings of the 1850s.

Elizabeth Siddal was not a conventional Victorian beauty. A petite frame was prized at the time and she was considered quite tall. Red hair was also not in favor, yet Rossetti and other Pre-Raphaelite artists depicted flowing red locks with such magnificence that they challenged the notion that red hair was both ugly and unlucky.

Later, Siddal’s hair would become famous when Charles Augustus Howell reported that it had continued to grow after death, supernaturally filling her coffin. While obviously untrue, it has become another Pre-Raphaelite tale that has passed into legend.

While Rossetti fed upon her face (how parasitic that sounds) and was inspired by his muse’s features, it is interesting to see how Elizabeth Siddal viewed herself.

Her self-portrait embraces the Pre-Raphaelite maxim of “truth to nature” yet it would never be described as what we consider the typical Pre-Raphaelite female. She portrays herself in a forthright manner; Siddal’s portrayal of herself is unflinching.

For more on Siddal, I recommend Lucinda Hawksley’s biographyand two books by Jan Marsh: Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood (no relation to this site) and The Legend of Elizabeth Siddal.

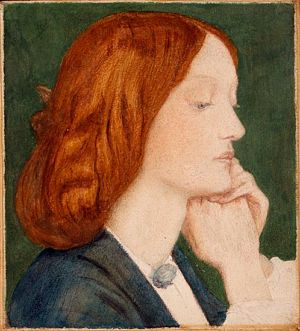

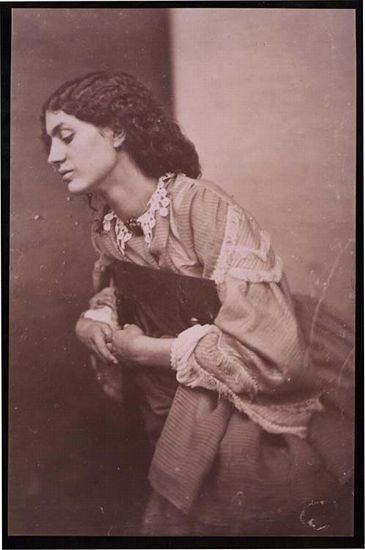

Annie Miller

Annie Miller was William Holman Hunt’s muse. Like Elizabeth Siddal, Miller’s image appears in early Pre-Raphaelite works. Hunt intended to marry her (eventually) and set about having her take lessons to become more refined. Although he set about to improve her life, their relationship did not end well and marriage never took place. Hunt was not overly pleased with her behavior while he traveled to the Middle East to paint. (For that matter, Elizabeth Siddal wasn’t ecstatic about Miller’s relationship with Rossetti.)

It is Rossetti’s images of Miller that I will share below, since Hunt removed Miller’s likeness from his paintings of her, including The Awaking Conscience and Il Dolce Far Niente.

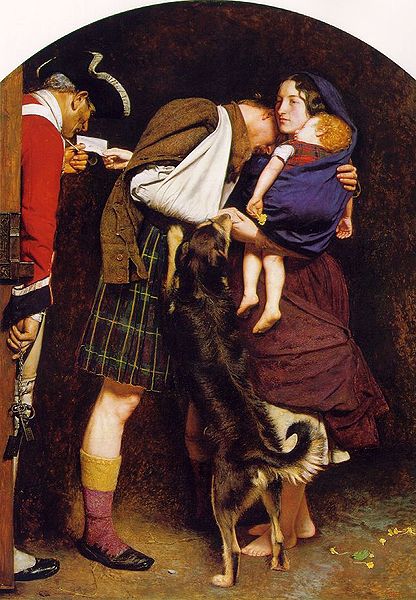

Effie Millais

Effie was trapped in a cold, loveless marriage to art critic John Ruskin when artist John Everett Millais fell in love with her. After a legal annulment (and the humiliation of having to prove her virginity), Millais and Effie were married. (See Pre-Raphaelite Marriages: Ruskin, Effie and Millais.)

Emma Thompson has written and starred in a movie about Effie’s marriage in which Dakota Fanning appears as Effie, often available for streaming on Amazon. The best biography I have read about the Effie/Ruskin/Millais triangle is Effie: The Passionate Lives of Effie Gray, John Ruskin and John Everett Millais by Suzanne Fagence Cooper; I highly recommend it.

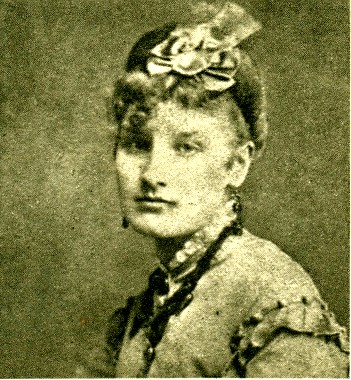

Fanny Cornforth

Fanny Cornforth may have been Rossetti’s truest female friend. Often disparaged by those close to Rossetti, she appears to have been unwavering in her loyalty. Her entry into his life inspired a new, sensuous aspect to his work. The first and most obvious example is Bocca Baciata (The Kissed Mouth). The title itself embraces physical pleasure.

Where Elizabeth Siddal was said to be thin and underweight due to illness, Fanny Cornforth was plumper, healthier, and robust. Siddal would be his idealized muse, a woman to put on a pedestal and admire. But Cornforth was a woman to experience life and laughter with, a woman to enjoy unashamedly. Unfortunately for her, she was not the woman Rossetti would marry.

As the years went on, she eventually became Rossetti’s housekeeper. Her days as his muse waned as his eyes sought out a different type of beauty for his work, yet she would remain a permanent fixture in his life. For more, I’d suggest reading Stunner: The Fall and Rise of Fanny Cornforth by Kirsty Stonell Walker.

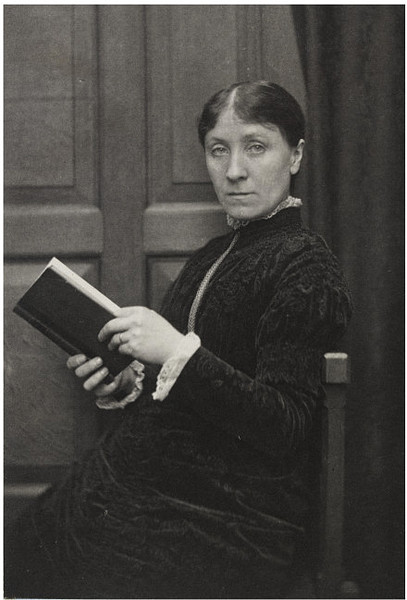

Georgiana Burne-Jones

Georgiana Burne-Jones became engaged to Edward Burne-Jones in her adolescence. She was known for her kind disposition and was a loving wife to “Ned.”

Georgiana, known as “Georgie,” was the fifth of eleven children and one of the “MacDonald sisters.” Her sister Agnes married Edward Poynter, a painter who eventually became Director of the National Gallery and, later, President of the Royal Academy. Their sister Louisa gave birth to future Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin and another sister, Alice, was the mother of Rudyard Kipling.

Maria Zambaco

Although the Burne-Joneses enjoyed a long and happy marriage, Ned did have an extramarital relationship with Maria Zambaco and she is seen repeatedly in his work. What started out as a passion turned incredibly ugly, however, and eventually his depictions of her seemed to have double meanings. (See my blog post The End of the Affair.)

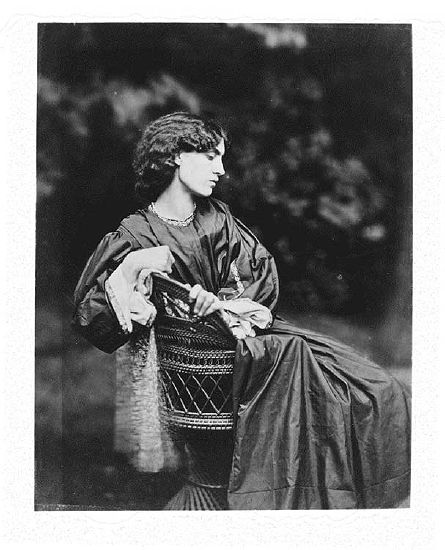

Jane Morris

Jane Morris was introduced to the Pre-Raphaelite circle in Oxford. While attending a theatre performance, she was spotted by Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones.

Later she married Rossetti’s close friend William Morris and several years after the death of Elizabeth Siddal, Rossetti and Jane Morris began a passionate romance. It’s a relationship that is still provocative and interesting to those of us interested in Pre-Raphaelite art, as William Morris apparently knew of it and while he must have been heartbroken, he was always loving and supportive towards Jane.

Rossetti’s paintings of Jane took on the same obsessive quality seen in his repeated drawings of Elizabeth Siddal years before, echoing Christina Rossetti’s poem In An Artist’s Studio. Once again, the artist feeds upon the face of a muse.

Alexa Wilding

When Rossetti spotted Alexa Wilding on a busy street, he immediately approached her to sit for him. She was quite tall, and even though he painted works featuring Alexa during the same time period he was painting Jane, they could not be more different in looks. They were physically different types, yet Rossetti would embellish and add his characteristic touches to both – those Rossetti lips, strong arms, and lengthened necks.

Kirsty Stonell Walker has written an excellent fictionalized account of Alexa’s life, A Curl of Copper and Pearl.

What about Pre-Raphaelite beauty in today’s woman?

It may seem as if I am pitting these women against each other and sizing them up according to physical appearance – that is not my intention at all. Rather, I’m trying to demonstrate that what we perceive today as Pre-Raphaelite beauty is, in fact, an amalgamation.

The Pre-Raphaelites were a varied group, and their individual perceptions of what was aesthetically pleasing have blended together into something beautiful and bold.

That is a liberating and inspiring concept. It tells us that we are each Pre-Raphaelite Stunners. It took several types of women to develop the Pre-Raphaelite ideal; it takes women of all types to make up our world.

Resist the narrow definitions of beauty that society uses to define us. Embrace what you feel are your strengths and silence the negative voice that finds fault. Look in the mirror, strike a pose, and know you are beauty personified.

Amen, sister! I was about to say that one thing uniting them was not fitting the conventional standard of beauty, but even that isn’t true when you consider Annie or some Alexa.

Hooray for the Sisterhood in all its glorious variety!

I love that Pre-Raphaelite art fell just outside the norms of conventional beauty for the time, and then went on to inspire the next generation (Art Nouveau, etc). And especially in Lizzie Siddal and Jane Morris’ case, the fact that they dressed without corsets and similar restrictions of the day is admirable.

Hello Stephanie. I am new to your lovely site and want to say that I enjoyed this post tremendously! Being an artist myself, I have long loved and taken inspiration from Pre-Raphaelite art. But just in the last year, I have dug deep to find out anything and everything about the immortal women who truly made these paintings beautiful. (I feel that I am “feeding upon their faces” and lives!) Again, wonderful post and I am so glad to have found your site!

Merissa

A wonderful blog. And I always thought that the male Pre-Raphaelites preferred only those women who would die for their art!

Wonderfully interesting post! Thanks for showing how the pre-raphaelite models did encompass a range of types. However, the problem remains that they are all young and beautiful, and in the case of Rossetti and Burne Jones, heavily stylized to the point of almost looking unreal. I suppose this is one of the criticisms of pre-raphaelite art – it shows an unreal, fantasy world – it doesn’t show the real world or real people as they actually are. Apart from Millais who moved on to portraiture, I can’t think of any pre raph works depicting middle aged or older women. Compare this with Rembrandt and the Dutch masters who really knew how to bring out the beauty and character in an old persons face and in everyday life.

This was so inspiring! People always said me I wasn’t pretty because I don’t the current beauty ideal, but thanks to you now I see that there’s so many ways of being beautiful and one just have to find hers!

Thank you so much!

Hello,I check your new stuff named “What is the ‘Pre-Raphaelite Woman’?” daily.Your writing style is awesome, keep doing what you’re doing! And you can look our website about proxy list.

Research on “why do so many pre-Raphaelite women have red hair?” led me to your website and gave me a very clear answer on that subject. I am trying to advise a friend who has to do a flower arrangement inspired by “Soul of the Rose” by Waterhouse. Clearly red flowers will have to feature in the arrangement. I have a broader interest, in that I live in Ewell Village, well known to the Pre-Raphaelites as they all visited Holman Hunt’s Uncle’s farm next to the village church (only its simple wooden barn survives) Ewell (it means “spring”) is the source of the Hogsmill River, which springs full-sized in the grounds of a local park in the heart of the village and it is this river in which the drowning Ophelia is shown in Millais’s painting (though the site was further away).

So, thanks for your help! this sort of research is invaluable and fascinating to your readers. EVN

This was a great article. The information is well organized regarding the artists, their muses, relationships, and timeline. I, too, am attuned to the pre raphaelite woman ideal and agree that we are all individuals innately endowed with the quality of beauty.