Happy Birthday to William Shakespeare, born on this day in 1564. Today is also the anniversary of the Bard’s death. Dare I say it? Dying on your birthday is a dramatically Shakespearean thing to do.

When a young group of artists founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848 they drew up a list of ‘Immortals’, made up of artists and historical figures they admired and sought to emulate. Shakespeare, of course, was on that list. Pre-Raphaelite artists and their followers would return to Shakespearean subjects repeatedly. I’ll share some of my favorite Pre-Raphaelite depictions of Shakespeare’s works in this post.

Millais’ Painting of Portia and its connection to Dame Ellen Terry

The model for Millais’ painting of Portia has often been incorrectly identified as Shakespearean actress Ellen Terry. The model was Kate Dolan, although the mistake was understandable as she was painted wearing Ellen Terry’s costume:

Of course I will lend you the dress (here it is.) or anything in the world that I possess, that could be of the very smallest service to you.

The dress was away in Scotland being cleaned for storing, or I should have sent it to you before–

Yours sincerely,

Ellen Terry

(Dated March 30, 1886)

Portia is the heroine of The Merchant of Venice. You may be familiar with one of her speeches:

The quality of mercy is not strain’d.

It droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven

Upon the place beneath. It is twice blest:

It blesseth him that gives and him that takes.

You can actually hear Terry delivering her lines as Portia in this 1911 recording.

It is Ellen Terry’s role as Lady Macbeth that captivates me, though. For one reason and one reason alone. Her famous beetle-wing dress. It has been immortalized in John Singer Sargent’s painting.

When it came to costuming, Dame Ellen Terry paid attention to the smallest detail. Her desire to create a gown for Lady Macbeth that would have a shimmering, serpent like appearance led to the design of this gown. Its iridescent green comes from thousands of beetle wings, a fragile affair that was recently restored.

As I read her memoirs, I was excited when I reached her performance as Lady Macbeth. The gown is so famous due to Sargent’s painting of it and I was eager to see if she would mention it. I was not disappointed. Not just because of the mention of the dress, but because of a brief glimpse into the production. Here is her description on Henry Irving as Macbeth:

“His view of “Macbeth”, though attacked and derided and put to shame in many quarters, is as clear to me as the sunlight itself. To me it seems as stupid to quarrel with the conception as to deny the nose on one’s face. But the carrying out of the conception was unequal.

When I think of his “Macbeth”, I remember him most distinctly in the last act after the battle when he looked like a great famished wolf, weak with the weakness of a giant exhausted, spent as one whose exertions have been ten times as great as those of commoner men of a rougher fiber and courser strength.

“Of all men else I have avoided thee.”

Once more he suggested, as only he could suggest, the power of Fate. Destiny seemed to hang over him, and he knew that there was no hope, no mercy.”

And the portion I was waiting for. Ellen Terry on the ‘Lady Macbeth’ gown:

“I am glad to think it is immortalized in Sargent’s picture. From the first I knew that picture was going to be splendid. In my diary for 1888 I was always writing about it:

“The picture of me is nearly finished, and I think it is magnificent. The green and blue of the dress is splendid, and the expression as Lady Macbeth holds the crown over her head is quite wonderful.”

Later, she continues:

Excerpt from Ellen Terry’s diary: “The picture is the sensation of the year. Of course opinions differ about it, but there are dense crowds round it day after day. There is talk of putting it on exhibition by itself.”

It was satisfying to see that she mentions Burne-Jones, a favorite artist of mine: “Sargent’s picture is almost finished, and it is really splendid. Burne-Jones yesterday suggested two or three alterations about the color which Sargent immediately adopted, but Burne-Jones raves about the picture.”

Further on, she shares her correspondence with her daughter concerning the gown:

From a letter I wrote to my daughter, who was in Germany at the time:

“I wish you could see my dresses. They are superb, especially the first one: green beetles on it, and such a cloak! The photographs give no idea of it at all, for it is in color that is so splendid. The dark red hair is fine. The whole thing is Rossetti- rich stained-glass effects, I play some of it well, but, of course, I don’t do what I want to do yet. Meanwhile I shall not budge an inch in the reading of it, for that I know is right. Oh, it’s fun, but it’s precious hard work for I by no means make her a ‘gentle, lovable woman’ as some of ’em say. That’s all pickles. She was nothing of the sort, although she was not a fiend, and did love her husband. I have to what is vulgarly called ‘sweat at it’ each night.”

The ‘Lady Macbeth’ gown has been mentioned online extensively:

Ellen Terry’s beetlewing gown back in limelight after £110,000 restoration

The Archeology of a dress

More on THAT dress: Victorian era dress, made with 1,000 beetle wings

And if the movie Brave is an indication, the ‘Lady Macbeth’ gown continues to inspire:

By the way, Terry was the great-aunt of actor Sir John Gielgud who describes her in his memoir: “She was a very Pre-Raphaelite actress. She had sat for painters like Rossetti, and she had known and talked with all the great men of her time–Tennyson, Browning, Ruskin, Wilde–and had learned a great deal from them. Yet she had a real humility. When you met her, you felt that she was ready to learn from children, or from anybody else with whom she came into contact. (Gielgud, John, An Actor and His Time, London: Sidgewick & Jackson, 1979)

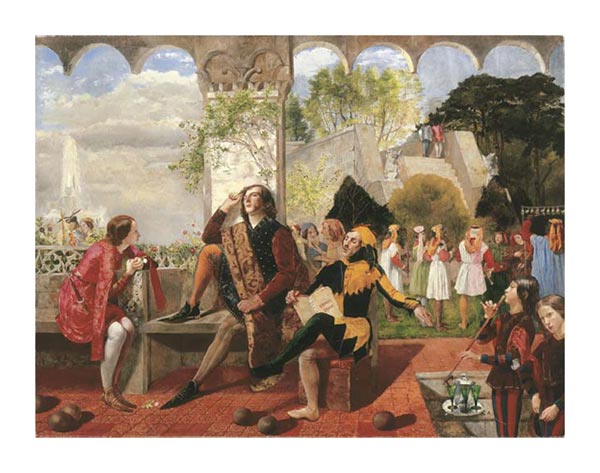

Walter Deverell’s Twelfth Night introduced Elizabeth Siddal to the Pre-Raphaelites

Walter Howell Deverell was in need of a model to portray Viola for his work in progress, Twelfth Night. It was Elizabeth Siddal who struck his eye while she worked in Mrs. Tozer’s hat shop. Fellow Pre-Raphaelite William Holman Hunt described Lizzie’s discovery:

“Rossetti at that date had the habit of coming to me with a drawing folio, and sitting with it designing while I was painting at a further part of the room…Deverell broke in upon our peaceful labours. He had not been seated many minutes, talking in a somewhat absent manner, when he bounded up, marching, or rather dancing to and fro about the room, and, stopping emphatically, he whispered, “You fellows can’t tell what a stupendously beautiful creature I have found. By Jove! She’s like a queen, magnificently tall, with a lovely figure, a stately neck, and a face of the most delicate and finished modelling: the flow of surface from the temples over the cheek is exactly like the carving of a Phidean goddess…I got my mother to persuade the miraculous creature to sit for me for my Viola in ‘Twelfth Night‘, and to-day I have been trying to paint her; but I have made a mess of my beginning. To-morrow she’s coming again; you two should come down and see her; she’s really a wonder; for while her friends, of course, are quite humble, she behaves like a real lady, by clear commonsense, and without any affectation, knowing perfectly, too, how to keep people respectful at a distance.”

Twelfth Night was the painting that introduced Lizzie into the Pre-Raphaelite world. She sat for many important Pre-Raphaelite works and is perhaps most famous for her portrayal of Ophelia in the painting by Sir John Everett Millais, also a work based on Shakespeare (Hamlet). In an interesting twist, Dante Gabriel Rossetti also appears in Deverell’s painting as the jester. Rossetti would become an important person in Lizzie’s life and there would come a time when she would model only for him. He became a tutor and mentor, encouraging her art. They had a long tumultuous relationship and married in 1860. Their story is a sad one. Lizzie was addicted to laudanum, they suffered the loss of a stillborn daughter, and Lizzie died of a laudanum overdose just two years after their marriage. Rossetti, consumed with guilt and despair, buried his only manuscript of the poems he had been working on with Lizzie in her coffin. Several years later he had her coffin exhumed to retrieve them.

Deverell died at 27 due to Bright’s disease.

Images from The Tempest

In The Tempest, Shakespeare tells us the story of Prospero, duke of Milan. Prospero was dethroned by his brother Antonio and abandoned at sea with his three year old daughter Miranda. Eventually they landed on an enchanted island, where the sole inhabitant is the creature Caliban. Prospero works his magic and places Caliban and all other spirits on the island under his control, including the spirit Ariel. Ariel is described as an ‘ayrie spirit’ (Air spirit) and was confined in a cloven pine by the witch Sycorax until Prospero broke the spell. Interestingly, Shakespeare isn’t clear about when Prospero became a sorcerer. Before or after landing on the island?

Years later, Prospero used his magic to create a tempest that caused his brother Antonio as well as Ferdinand, Sebastian, and others to become shipwrecked on the island.

When Millais painted Ferdinand he used fellow Pre-Raphaelite F.G. Stephens as his model. Stephens describes his experience posing for the painting in The Life and Letters of Sir John Everett Millais:

“In the summer and autumn of 1849 he [Millais] executed the whole of that wonderful background, the delightful figures of the elves and Ariel, and he sketched in the Prince himself. The whole was done upon a pure white background, so as to obtain the greatest brilliancy of the pigments. Later on my turn came, and in one lengthy sitting Millais drew my most un-Ferdinand-like features with a pencil upon white paper, making, as it was, a most exquisite drawing of the highest finish and exact fidelity. In these respects nothing could surpass this jewel of its kind. Something like it, but softer and not quite so sculpturesque, exists in the similar study Millais made in pencil for the head of Ophelia, which I saw not long ago, and which Sir W. Bowman lent to the Grosvenor Gallery in 1888.”

My portrait was completely modelled in all respects of form and light and shade, so as to be a perfect study for the head thereafter to be painted. The day after it was executed Millais repeated the study in a less finished manner upon the panel, and on the day following that I went again to the studio in Gower Street, where ‘Isabella’ and similar pictures were painted. From ten o’clock to nearly five the sitting continued without a stop, and with scarcely a word between the painter and his model. The clicking of his brushes when they were shifted in his palette, the sliding of his foot upon the easel, and an occasional sigh marked the hours, while, strained to the utmost, Millais worked this extraordinary fine face. At last he said, “There, old fellow, it is done!” Thus it remains as perfectly pure and as brilliant as then –fifty years ago– and it now remains unchanged. For me, still leaning on a stick and in the required posture, I had become quite unable to move, rise upright, or stir a limb till, much as I were a stiffened lay-figure, Millais lifted me up and carried me bodily to the dining-room, where some dinner and wine put me on my feet again. Later the till then unpainted parts of the figure of Ferdinand were added from the model and a lay-figure.”

The subject of the painting is Ferdinand, son of the King of Naples. When the King’s ship wrecks upon Prospero’s island, Ferdinand was separated from the rest of his shipmates. He was led by Ariel’s enchanting music to Prospero’s cell where he meets Miranda. Miranda believes him to be a spirit at first, ‘nothing natural I ever saw so noble’. Ferdinand speaks to her as ‘the goddess on whom these airs attend’.

Although not strictly a Pre-Raphaelite, the works of John William Waterhouse are definitely Pre-Raphaelite in style. He painted Miranda from The Tempest twice; both works depict her as she looks upon the storm created by her father.

Waterhouse has captured the drama of nature, the waves exhibit the strength of the storm that will soon capsize the ship and its passengers. Miranda’s face is half-turned, so we can not read her expression. We can only use Shakespeare’s lines to learn her feelings:

If by your art, my dearest father, you have

Put the wild waters in this roar, allay them.

The sky, it seems, would pour down stinking pitch,

that the sea, mounting to th’ welkin’s cheek,

Dashes the fire out. Oh, I have suffered

With those that I saw suffer. A brave vessel

Who had, no doubt, some noble creature in her

Dashed all to pieces. Oh, the cry did knock

Against my very heart!

Perdita by Frederick Sandys

Perdita was painted by Frederick Sandys with Mary Emma Jones as the model. Also known by her stage name Miss Clive, Mary Emma Jones appears in several of Sandys’ works. They never married, but the couple did have ten children together. Sandys was a bit of a rogue when it came to his love life. In addition to Jones, he had a lengthy affair with Keomi Gray (also see More on Keomi Gray) and she appears in many of his works.

Sandys’ Perdita has definite Rossettian influences to my eye, which is hardly surprising as he shared Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s studio for a while and at one point, Rossetti even accused Sandys quite blatantly of plagiarism. Of course, there’s also a nod to Botticelli.

In Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale, Perdita is the daughter of Leontes (King of Sicilia) and Hermione. Unfortunately, Leontes wrongly believes that Hermione has been unfaithful with Polixenes (King of Bohemia) and that they have conceived a child. He imprisons his wife and Perdita, who actually is his daughter, is born in captivity. She is later abandoned on a seashore where she is discovered and raised by a shepherd.

In the second half of the play, Perdita has grown into a sixteen-year-old beauty. She has fallen in love with Florizel, son of Polixenes. Polixenes strongly objects to this relationship, not realizing that Perdita isn’t actually a shepherd’s daughter but the daughter of Hermione and Leontes. Eventually, as in all Shakespearean identity conundrums, Perdita learns who she truly is and is reunited with Hermione. This is a rudimentary overview on my part and I am not doing The Winter’s Tale justice. In 2013, The Royal Shakespeare Company performed a production of the play starring Tara Fitzgerald, Jo Stone-Fewings and Adam Levy. I was happily surprised to find this video with the cast where, around the 1:27 minute mark, Tara Fitgerald mentions in passing that in this production they’ve set the play in the 1860s and describes the characters as free-spirited and Pre-Raphaelite.

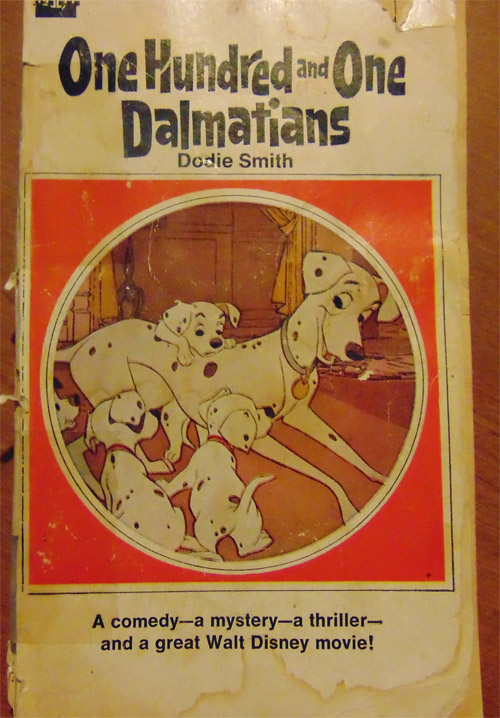

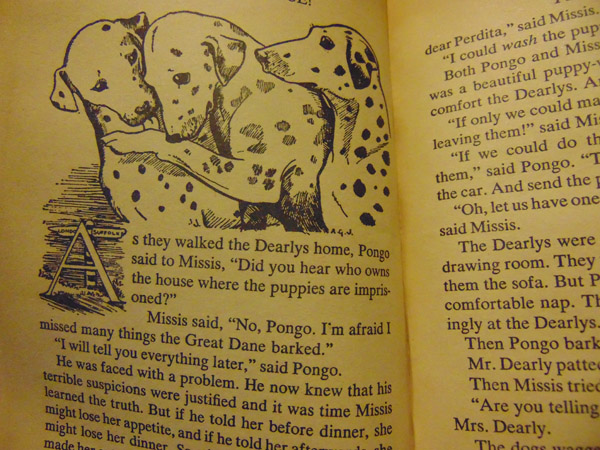

Perhaps you are more familiar with this Perdita? If you’ve never read the book, you might be unaware that Pongo’s wife was actually named Missis. Perdita is a different Dalmatian and her name was a deliberate choice by the author Dodie Smith.

Perhaps you are more familiar with this Perdita? If you’ve never read the book, you might be unaware that Pongo’s wife was actually named Missis. Perdita is a different Dalmatian and her name was a deliberate choice by the author Dodie Smith.

I adored the Disney cartoon as a child and have happy memories of repeatedly listening to a recorded version on vinyl (a record I still have, by the way). When I finally read Dodie Smith’s book at age eleven I was enthralled and I have revisited that story several times over the years. Although I still love the cartoon, it is missing some of the nuance and charm of Smith’s story. Perdita is a liver-spotted dalmatian, lost from home and missing the pups that were taken from her. The Mr. and Mrs. Dearly rescue her; Pongo and Missis take her into their hearts. Despite the fact that she is weak and underfed, she helps wash Pongo and Missis’ pups and bonds with them while missing her own. Both the cartoon and later live action versions combine Missis and Perdita into one character and I suspect Disney might have found the alliteration of ‘Pongo and Perdita’ to be catchier than Pongo and Missis.

“We’ll call her Perdita,” said Mrs. Dearly, and explained to the Nannies that this was after a character in Shakespeare. “She was lost. And the Latin word for lost was perditus.” Then she patted Pongo, who was looking particularly intelligent, and said anyone would think he understood. And indeed he did. For though he had very little Latin beyond ‘Cave canum’, he had, as a young dog, devoured Shakespeare (in a tasty leather binding). –One Hundred and One Dalmatians, Dodie Smith

Bring on the Ophelias!

You can’t mention the Pre-Raphaelites and Shakespeare without talking about their many depictions of Hamlet’s ingenue Ophelia.

When John Everett Millais painted Ophelia he chose to depict her in the moments just before she drowns, a bold choice as most previous artists portrayed Ophelia before she ever enters the water. This isn’t the only striking aspect of his painting, however. In the midst of this picture of death, the plant life is rich and colorful. Each plant, whether in background or foreground, is given equal attention and no detail is spared. The botanical aspects of Ophelia are so important that Millais chose to paint the background prior to adding in the figure, which was a very unusual move. More on the flowers here. Elizabeth Siddal posed as Ophelia and developed pneumonia while laying in a bathtub. More on Siddal here and thoughts on what shapes our perception of Siddal here.

More Pre-Raphaelite paintings of Ophelia:

King Lear

King Lear is a tragic play filled with anger and grief. It is wrought with suffering and explores issues of old age and family as only Shakespeare could explore them. William Holman Hunt took inspiration from a quotation of King Lear for his painting The Hireling Shepherd (pictured above). It is from the lines of the Fool, who says:

Sleepest or wakest thou, jolly shepherd?

Thy sheep be in the corn.

And for one blast of thy minikin mouth,

Thy sheep shall take no harm.

Hunt portrays the shepherd as neglecting his flock, too busy flirting with the shepherdess to see that they are falling ill. In his hand he holds a death’s head moth. The moth is impressive once you notice it, Hunt captured it in minute detail. See Twelve Facts about Death’s Head Moths. The shepherdess, also distracted and neglectful, has a young lamb in her lap that will also soon fall ill since it is eating a green apple.

Hunt’s painting is striking. The colors are vivid and the detail is superb. But it is Ford Madox Brown’s paintings of King Lear that excite me, because they were born from the passion of a viewer who was captivated by the performance of the play. Lucinda Hawksley describes this in Essential Pre-Raphaelites:

“Ford Madox Brown’s fascination for Shakespeare’s King Lear began in 1843 (reputedly after seeing William Charles Macready playing Lear on the London stage). Brown began to sketch scenes from the play feverishly — producing 16 in one year. Henry Irving, who later played Lear to great acclaim, became the owner of several of these.”

I blogged about this when Carrie Fisher died because this is the kind of tale that resonates with me. I can easily imagine an artist being swept away by an outstanding performance, a performance that inspired him to create his own images of the saga. It is a completely different experience for us now. Most of us see movies far more often than a live production. And if we want, we can easily own the movie on dvd for us to watch again and again. But what of Ford Madox Brown? A play is a different animal entirely. Performances can differ from night to night; with each new audience a new experience is created. So I see Ford Madox Brown’s work as an attempt to capture what was inspired by that one performance. He may not have painted the exact actors, scenery or costumes from that performance, but he painted the passion for the story of King Lear that the performance inspired.

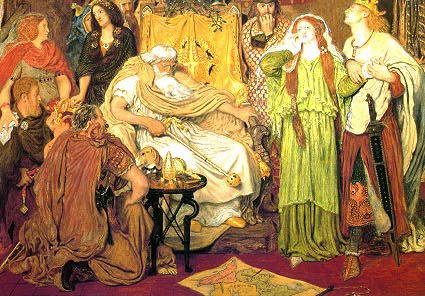

Ford Madox Brown’s painting Cordelia at the Bedside of Lear:

Cordelia is modeled by Brown’s wife Emma. The Fool, staring so intently at Lear, was modeled by Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Cordelia is modeled by Brown’s wife Emma. The Fool, staring so intently at Lear, was modeled by Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

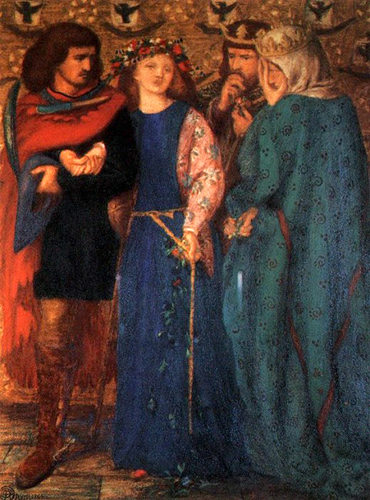

Later, Brown painted an earlier scene from the play. Cordelia’s Portion:

In Will of the World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare, author Stephen Greenblatt proposes that Shakespeare was possibly contemplating retirement –and thinking about its perils– when he wrote King Lear. “The tragedy is his greatest meditation on extreme old age; on the painful necessity of renouncing power; on the loss of house, land, authority, love, eyesight, and sanity itself.” Greenblatt describes it well. It is one of the most tumultuous Shakespearean dramas I have ever seen.

I’ve read King Lear in its entirety. It is a beautiful text to read, but I was left feeling somewhat dissatisfied. Shakespeare did not write his plays to be read, he wanted them to be seen! Acted! Felt! I wanted to be involved in the story as Ford Madox Brown was. Searching for an adaptation to watch, I was happy to find a production of King Lear starring Sir Ian McKellen on Netflix. I highly recommend it. It is a masterful performance with a talented ensemble. And I’m not alone in my admiration of it — visitor comments on the PBS Great Performances page describes King Lear as a “life-altering experience, proving, once again, how great art presented intimately and at home, can illuminate the intricacies of a classic play in startling new ways.” Reading Shakespeare can be a beautiful experience, but it can never be the same as seeing it performed. Not just performed, but performed well.

There is a life cycle to art and creativity. Shakespeare continues to inspire. As do the Pre-Raphaelites. Since starting this website, I have been lucky enough to have met many people whose work is often a nod to the Pre-Raphaelites and their associates. I love Ford Madox Brown’s representations of King Lear because it is a perfect example of how someone’s creativity will stimulate the inventiveness of others. In Act 1, Scene 1 of King Lear, Shakespeare wrote that “Nothing will come of nothing.” And now it is my firm belief that Art will come from Art.

***

Interested in more about Pre-Raphaelite art and Shakespeare? I wrote an article about Elizabeth Siddal and Ophelia in this issue of Shakespeare magazine. It’s free to read online. You can follow Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood on Facebook and Twitter.