Truth to nature was one of the main tenets of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and an excellent example of this can be seen in the Death’s Head moth in William Holman Hunt’s painting The Hireling Shepherd (above). I’ve blogged about it many times before; it’s part of my Shakespeare post that I share yearly on the Bard’s birthday.

William Holman Hunt took inspiration from a quotation of King Lear for his painting The Hireling Shepherd. It is from the lines of the Fool, who says:

Sleepest or wakest thou, jolly shepherd?

Thy sheep be in the corn.

And for one blast of thy minikin mouth,

Thy sheep shall take no harm.

Hunt portrays the shepherd as neglecting his flock, too busy flirting with a beautiful young lady to see that they are falling ill. In his hand, he holds a Death’s Head moth.

The moth is impressive once you notice it; Hunt captured it in minute detail. The shepherdess, also distracted and neglectful, has a young lamb in her lap that will also soon fall ill since it is eating a green apple.

You can see that Holman Hunt painted the Death’s Head moth with precision. My daughter owns an actual specimen, which she’s let me borrow for this post.

The Death’s Head moth is an eye-catching creature and it lends itself well to art and fiction. The moth is familiar to many of us now as an integral part of Thomas Harris’ Silence of the Lambs, but that is not its first appearance in literature by any means.

Bram Stoker used the moth in chapter 21 of Dracula in a somewhat gruesome scene where Renfield, a patient in an asylum, describes how Dracula has sent him death’s head moths and rats for him to feed on.

“…He used to send in the flies when the sun was shining, Great big fat ones with steel and sapphire on their wings; and big moths, in the night, with skull and cross-bones on their backs.” Van Helsing nodded to him as he whispered to me unconsciously:–“The Acherontio atropos of the Sphinges –what you call the Death’s-head moth”!

Then he began to whisper: “Rats, rats, rats! Hundreds, thousands, millions of them and every one a life; and dogs to eat them, and cats too. All lives!”–Dracula, Bram Stoker

You might enjoy my post Did Elizabeth Siddal Inspire Bram Stoker?

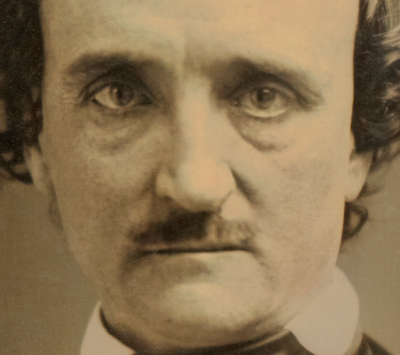

Edgar Allan Poe used the moth in his 1846 story The Sphinx, a fascinating tale of death and paranoia.

“But the chief peculiarity of this horrible thing was the representation of a Death’s Head, which covered nearly the whole surface of its breast, and which was as accurately traced in glaring white, upon the dark ground of the body, as if it had been there carefully designed by an artist. While I regarded the terrific animal, and more especially the appearance in its breast, with a feeling of horror and awe –with a sentiment of forthcoming evil, which I found it impossible to quell by any effort of the reason, I perceived the huge jaws at the extremity of the proboscis suddenly expand themselves, and from there proceeded a sound so loud and so expressive of woe, that it struck upon my nerves like a knell, and as the monster disappeared at the foot of the hill, I fell at once, fainting to the floor.” The Sphinx, Edgar Allan Poe

While the Death’s Head moth is striking due to its sinister markings, I can find no other instances of its use in Pre-Raphaelite art (although, if you know of any please let me know). Most artists in the Pre-Raphaelite circle seemed to gravitate more to the symbolism of butterflies. This is not unusual; butterflies have been used artistically for time immemorial.

Sir John Everett Millais’ use of a butterfly in The Blind Girl is a poignant touch.

The blind girl can not enjoy the butterfly that has landed on her cloak or the double rainbow behind her. She experiences the world through touch, smell, and sound. Look at her hand and you see she’s lightly fingering the grass, experiencing her surroundings in a tactile way.

Interestingly, the butterfly was misidentified by Victorian art critic M.H. Spielmann as a Death’s Head moth. It’s actually a tortoise-shell butterfly according to the artist’s son, John Guille Millais, in his two-volume work The Life and Letters of Sir John Everett Millais. J.G. Millais shares what his father’s contemporaries had to say about the work, as well as a description of it.

“The Blind Girl, a still more pathetic subject, is described by Spielmann as “the most luminous with bright golden light of all Millais’ works, and for that reason the more deeply pathetic in relation to the subject. Madox Brown was right when he called it a ‘religious picture, and a glorious one,’ for God’s bow is in the sky, doubly–a sign of Divine promise specially significant to the blind. Rossetti called it ‘one of the most touching and perfect things I know,’ and the Liverpool Academy endorsed his opinions by awarding to it their annual prize, although the public generally favored Abraham Solomon’s ‘Waiting for the Verdict’. Sunlight seems to issue from the picture, and bathes the blind girl — blind alike to its glow, to the beauties of the symbolic butterfly that has settled upon her, and to the token in the sky.” The Life and Letters of Sir John Everett Millais, vol. I, J.G. Millais

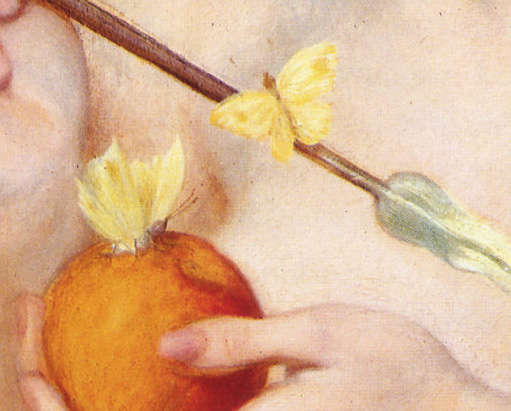

Dante Gabriel Rossetti included butterflies in both Venus Verticordia and Sybilla Palmifera.

Sybilla Palmifera is filled with symbolism, which you can read about in the post Oracles and Sybils. Two butterflies, representing the human soul, fly under poppies, a flower symbolic of death and remembrance.

Venus Verticordia means ‘Venus, turner of hearts’ and is indicative of Venus’ power to change the hearts of women from lust to chastity.

Yellow butterflies are visible along her halo as well as on her apple and arrow. I believe that as in Sybilla Palmifera the butterflies represent the human soul and in Rossetti Painter and Poet, author JB Bullen points out that they may be souls of her past lovers.

In both Sybilla Palmifera and Venus Verticordia, Rossetti used model Alexa Wilding. Often mistaken for Elizabeth Siddal in The Blessed Damozel, Alexa appears in many of his later works; you can read about his frequently used models here. Alexa is the subject of author Kirsty Stonell Walker’s novel A Curl of Copper and Pearl, which I absolutely recommend.

Albert Joseph Moore’s painting The Green Butterfly captures an ephemeral moment as a lovely young lady watches a butterfly in flight.

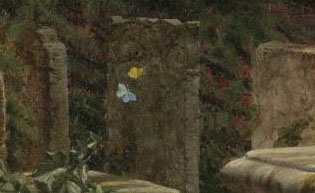

Look closely in Henry Alexander Bowler’s painting The Doubt: Can these Dry Bones Live? Two butterflies flit among the gravestones, symbols of life and its impermanence.

Evelyn De Morgan’s painting Death of a Butterfly may be exploring death or it may be about transformation. Perhaps it is not just a contrast of dark and light, but endings and beginnings.

We still use Lepidoptera quite often artistically. The butterfly in Peter S. Beagle’s The Last Unicorn is a fluttering delight and A.S. Byatt uses the Victorian interest in collecting specimens in a strange and shocking way in Angels and Insects, a collection of two novellas.

Most recently, Guillermo Del Toro used moths and butterflies to represent two opposing characters in Crimson Peak.

Moths and butterflies live such a fascinating existence that it is no wonder we use them symbolically. Their very lives are an evolution. It’s a dramatic metamorphosis from egg to larva, then pupa to adult.

First a caterpillar and after a period of time, they emerge from the chrysalis as a new, winged being.