The Portrait is a poem I’ve wanted to write about for a while now, because writing about things is how I unpack and explore them. One thing I love about poetry, though, is its prismatic quality. The facets I see may not be what you see, but if we compare notes then new colors emerge. That’s where the fun is.

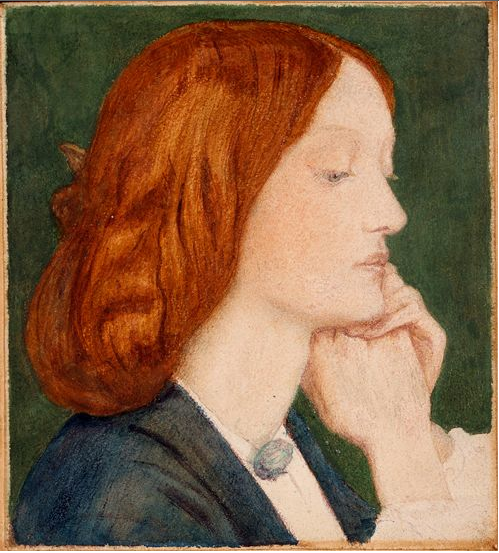

Dante Gabriel Rossetti completed The Portrait in 1869, the year he had Elizabeth Siddal exhumed in order to retrieve the manuscript of poems he had buried with her in 1862. It is reminiscent of his 1847 work On Mary’s Portrait Which I Painted Six Years Ago. Rossetti frequently created double works, poems that accompanied paintings. This one has no specific association, but it is easy to think of images of Siddal while reading it. For me, Beata Beatrix comes to mind as it is frequently seen as a posthumous tribute to her. For Rossetti, visual art and the written word were entwined and The Portrait is a perfect example of art-inspired poetry.

The Portrait

This is her picture as she was:

It seems a thing to wonder on,

As though mine image in the glass

Should tarry when myself am gone.

I gaze until she seems to stir,—

Until mine eyes almost aver

That now, even now, the sweet lips part

To breathe the words of the sweet heart:—

And yet the earth is over her.

Alas! even such the thin-drawn ray

That makes the prison-depths more rude,—

The drip of water night and day

Giving a tongue to solitude.

Yet only this, of love’s whole prize,

Remains; save what in mournful guise

Takes counsel with my soul alone,—

Save what is secret and unknown,

Below the earth, above the skies.

In painting her I shrin’d her face

Mid mystic trees, where light falls in

Hardly at all; a covert place

Where you might think to find a din

Of doubtful talk, and a live flame

Wandering, and many a shape whose name

Not itself knoweth, and old dew,

And your own footsteps meeting you,

And all things going as they came.

A deep dim wood; and there she stands

As in that wood that day: for so

Was the still movement of her hands

And such the pure line’s gracious flow.

And passing fair the type must seem,

Unknown the presence and the dream.

‘Tis she: though of herself, alas!

Less than her shadow on the grass

Or than her image in the stream.

That day we met there, I and she

One with the other all alone;

And we were blithe; yet memory

Saddens those hours, as when the moon

Looks upon daylight. And with her

I stoop’d to drink the spring-water,

Athirst where other waters sprang;

And where the echo is, she sang,—

My soul another echo there.

But when that hour my soul won strength

For words whose silence wastes and kills,

Dull raindrops smote us, and at length

Thunder’d the heat within the hills.

That eve I spoke those words again

Beside the pelted window-pane;

And there she hearken’d what I said,

With under-glances that survey’d

The empty pastures blind with rain.

Next day the memories of these things,

Like leaves through which a bird has flown,

Still vibrated with Love’s warm wings;

Till I must make them all my own

And paint this picture. So, ‘twixt ease

Of talk and sweet long silences,

She stood among the plants in bloom

At windows of a summer room,

To feign the shadow of the trees.

And as I wrought, while all above

And all around was fragrant air,

In the sick burthen of my love

It seem’d each sun-thrill’d blossom there

Beat like a heart among the leaves.

O heart that never beats nor heaves,

In that one darkness lying still,

What now to thee my love’s great will

Or the fine web the sunshine weaves?

For now doth daylight disavow

Those days,—nought left to see or hear.

Only in solemn whispers now

At night-time these things reach mine ear;

When the leaf-shadows at a breath

Shrink in the road, and all the heath,

Forest and water, far and wide,

In limpid starlight glorified,

Lie like the mystery of death.

Last night at last I could have slept,

And yet delay’d my sleep till dawn,

Still wandering. Then it was I wept:

For unawares I came upon

Those glades where once she walk’d with me:

And as I stood there suddenly,

All wan with traversing the night,

Upon the desolate verge of light

Yearn’d loud the iron-bosom’d sea.

Even so, where Heaven holds breath and hears

The beating heart of Love’s own breast,—

Where round the secret of all spheres

All angels lay their wings to rest,—

How shall my soul stand rapt and aw’d,

When, by the new birth borne abroad

Throughout the music of the suns,

It enters in her soul at once

And knows the silence there for God!

Here with her face doth memory sit

Meanwhile, and wait the day’s decline,

Till other eyes shall look from it,

Eyes of the spirit’s Palestine,

Even than the old gaze tenderer:

While hopes and aims long lost with her

Stand round her image side by side,

Like tombs of pilgrims that have died

About the Holy Sepulchre.

These lines have shades of Echo and Narcissus to me and it makes me ponder reflections and echoes and what they might have meant to Rossetti. And what they mean to myself, for that matter. Perhaps the speaker of the poem is an embodiment of Narcissus seeking his own reflection and he sees images of his beloved as reflections of himself. He inserts his own reflection into the poem with the line As though mine image in the glass should tarry when myself am gone.

As I said before, Beata Beatrix is the painting I think of when reading The Portrait. Seen as a posthumous tribute to the artist’s wife, Rossetti had sketched studies of Elizabeth Siddal as Beatrice before her death due to a laudanum overdose in 1862. Later, he relied on those studies to create this magnificent image of Beatrice on the brink of death. In the background of Beata Beatrix, we see the figure of Dante and the allegorical figure of Love. A dove delivers to her hand a poppy, a symbolic and poignant choice. Poppies are the source of opium from which laudanum is derived.

Dante loved Beatrice on earth, but once she died his love for her evolved into a different thing altogether. Still feeling a need for her and her purity, he cast her as his guide in La Divina Commedia.

Beata Beatrix blurs the lines between Beatrice Portinari and Elizabeth Siddal. It helps cement our perception of Lizzie as an idealized love in Rossetti’s life, a love now in heaven. As Dante cast Beatrice as his heavenly guide in his Commedia, Rossetti now portrayed his wife as his own Beatrice. This coupled with the fact that Rossetti later had Lizzie exhumed to retrieve the poetry buried with her has created an air of tragedy around her name.

This theme of losing a beloved occurred frequently in Rossetti’s work, long before the loss of his wife. Drawing inspiration from Edgar Allan Poe’s The Raven, Rossetti’s poem The Blessed Damozel explores the theme of lovers separated by death. Like Poe’s Lenore, the damozel (an archaic form of damsel) has died and Rossetti introduces her to us as she looks down upon her lover from heaven. Rossetti later told Hall Caine ‘I saw that Poe had done the utmost it is possible to do with the grief of the lover on earth, and so I determined to reverse the conditions and give utterance to the yearning of the loved one in heaven.’ You can read the full text of the poem here.

Perhaps, then, we can read The Portrait as an extension of The Blessed Damozel. What if we read the poem as if the narrator is the damozel’s artist lover, contemplating her image on earth? It’s an interesting way to read it. I’m sure that wasn’t Rossetti’s intention, but it’s a fun diversion.

The Raven may have contributed to the seeds of The Blessed Damozel, but Poe’s influence on Rossetti’s work does not end there. I definitely see The Portrait as a work that is interwoven with Rossetti’s story St. Agnes of Intercession, which in turn was influenced by Poe’s story The Oval Portrait (see my post Aesthetic Vampirism).

I see The Portrait as as poem that touches on artists, muses, and creation. The speaker grabs at flitting memories ‘like leaves through which a bird has flown’, physical memories that may have been moments forgotten and ignored until the muse was gone and no more memories can be made. Her image takes on new and deeper meanings because it is all he has. Perhaps he is giving us a glimpse at the intensity with which he viewed his own portraits and what his work meant to him.

The poem captivates me because it is yet again a blurring of art, life, and death that I see so often in Rossetti’s work. It speaks to me, probably because much of what I find touching and beautiful in life has distinct traces of melancholy — and melancholy is something that Rossetti understood and expressed so well.

This is her picture as she was:

It seems a thing to wonder on,

As though mine image in the glass

Should tarry when myself am gone.

I gaze until she seems to stir,—

Until mine eyes almost aver

That now, even now, the sweet lips part

To breathe the words of the sweet heart:—

And yet the earth is over her.